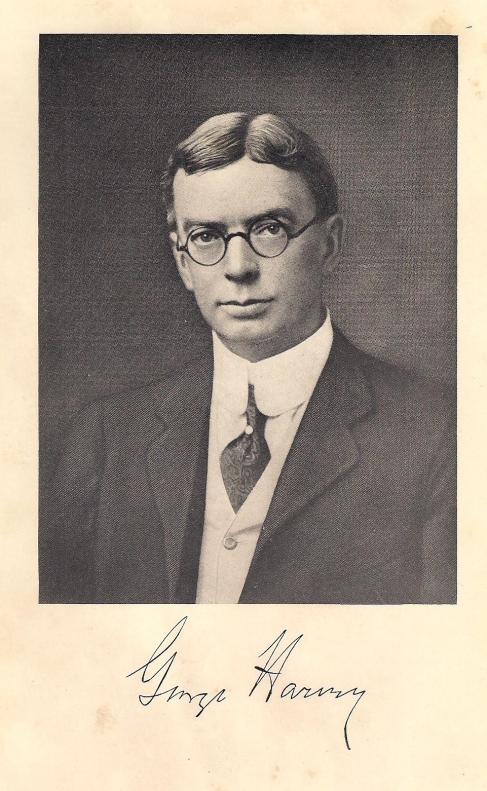

Few men held as much influence paired with humble perspective as did Ambassador George Harvey. As a journalist, statesman and diplomat for more than forty years, he had shaped history on more than one occasion. Yet, he approached his work as self-deferential service not an opportunity to secure glory among great men.

Few men held as much influence paired with humble perspective as did Ambassador George Harvey. As a journalist, statesman and diplomat for more than forty years, he had shaped history on more than one occasion. Yet, he approached his work as self-deferential service not an opportunity to secure glory among great men.

Appointed by President Harding as Ambassador to Great Britain in 1921, Harvey returned home upon the death of the President and subsequent succession by Calvin Coolidge in the summer of 1923. Coolidge and Harvey hit it off immediately. Both Vermonters, they possessed in like measure an ability to distill the intricate details of each policy question into its essential parts. As Coolidge honors him in his Autobiography, he would learn a “large amount” from Ambassador Harvey on the situation in Europe who “not only had a special aptitude for gathering and digesting information of that nature, but had been located at London for two years, where most of it centered” (pp.187-8).

Their first meeting, shortly after Coolidge succeeded to the Presidency, is recounted in Willis Johnson’s excellent biography, George Harvey: A Passionate Patriot. It was an opportunity for Coolidge to drill, through a series of rapid fire questions, a man who knew the “lay of the land” in Europe as well as domestically. Coolidge benefited immensely from Harvey’s political instincts. It was not that Harvey told Coolidge what needed to be done for both men knew that the incoming President, ridiculed as “provincial,” had a firmer grasp on affairs than most of the political class did. Harvey furnished the foundation for Coolidge to proceed with the assurance that the new President’s grasp of the situation was sound.

Ambassador Harvey provided Coolidge with an experienced perspective of one who had been “over there” and perceived political attitudes at home going into 1924. The task of securing nomination and election as well as the settlement of war debt and protection of American interests abroad needed men not only of intelligence but also of wisdom and circumspection. It was for this reason that Harvey, combining these qualities, became such an asset to President Coolidge.

While Coolidge would meet with Harvey more frequently than Harding ever did, the Ambassador would notice, favorably, that Coolidge sought advice without depending on it. Coolidge welcomed input but made the final decision himself. That, too, is a distinguishing mark of good leaders. History has seen its share of people who thought themselves greater than they were subsequently misleading the country because of a failure to seek informed opinions outside themselves. Coolidge never indulged such arrogance, explaining his approach this way,

“It has been my policy to seek information and advice wherever I could find it. I have never relied on any particular person to be my unofficial adviser. I have let the merits of each case and the soundness of all advice speak for themselves. My counselors have been those provided by the Constitution and the law” (Autobiography, p.188).

It was on both fronts, domestically and internationally, that Harvey proved his worth as a faithful advocate, dedicated diplomat and tenacious journalist. It was Harvey who, as Ambassador, settled the first of many war debt negotiations. That initial agreement paved the way for the rest of Europe to address their obligations. Not everyone did so but it was America and Great Britain who bore the weight of leadership around the world. Under that leadership, repayment of debts incurred by American aid during World War I found resolution. Harvey praised any nation who soberly committed to its duties. While other nations came to Washington to talk about the weather, “Great Britain arrived and talked business” (Johnson p.343). The settlement was not an easy one: Britain’s share of war debt was $150-200 million annually for sixty years, the terms placing her Majesty’s government in a position to strengthen credit so that only 2.5% in interest could be paid.

By paying its debts, Britain was telling the world how important it is to live responsibly, whether as nations or individuals. It was this very attitude, exemplified by the Coolidge administration, that America expected of itself. It was this seriousness about tackling the problem of debt — in contrast to indecision or worse, complacency — that distinguished the status of a world power from that of subsistence as a mere hireling, dependent on the actions of others for its welfare and best interests. America took its responsibilities seriously and, by resolving on a rule here (paying down the national debt, cutting taxes and reducing Federal expenditures) that the rest of the world could emulate, sent a message that freedom from rather than enslavement to debt forms the wise and sure basis of future economic and political success.

It was Harvey, having retired as Ambassador, who returned to the calling of journalism and was instrumental in explaining the issues at stake in the 1924 election. He was no partisan Republican, as he made plain: He first supported Coolidge because he knew him to be right and then, as he wrote Coolidge, because “you were you.” He would commend Coolidge in personal correspondence to King George V, sending the monarch his own biographical sketch of the new President so that Britain would also understand, and appreciate, the “Yankee” who now led America (Johnson p.375).

As editor of the North American Review, Harvey took up the task of unraveling fact from fiction to navigate through the morass of accusations and counter-claims. In his “Coolidge or Chaos” articles, Harvey exposed the plan then underway to try to throw the election into the House of Representatives, being the second time this honorable man thwarted a plot to manipulate an electoral choice by the people (the first being perpetrated against Cleveland in 1892). The plot was averted by his timely action that informed voters of what was truly at stake for the country.

Whether as journalist or diplomat, Harvey served his country faithfully. He knew his work, executed it conscientiously and answered the call to serve even as his health gave way, dying in August of 1928. His instincts were always sound, as seen when he accurately predicted the electoral victory for Coolidge in 1924, state-by-state, weeks before results were known (Johnson p.413). He seemed to be a man placed at the right time to serve his country where it needed him most.

Introducing Johnson’s biography, former President Coolidge, looked back with effusive approval for his dear friend’s life and accomplishments, writing in June 1929, “A character such as Colonel George Harvey possessed would make him an intense, even an almost fanatical American. He was not wanting in a world vision. He did not lack a vision on any subject. But his ideal of world service was to keep the United States free and unencumbered by any artificial limitations that might hamper it in serving humanity in accordance with its own judgment, in its own time and in its own way. There was little about him that was legalistic. If something ought to be done, it was his way to go and do it. He was purely practical and purely patriotic. As a journalist and author, a politician and a statesman, he left a broad and deep mark on the times in which he lived. Not only our own Country, but the world at large has profited by the life and action of Colonel George Harvey. It is a satisfaction to feel that he was my friend.”

He was one of many exceptional Americans of whom we can, joining with Coolidge, be proud. He remains, among many throughout our history, “worthy of the name American,” as Coolidge would say in a different context. His love of our country and pursuit of the welfare of all its people deserves our renewed study and grateful respect.