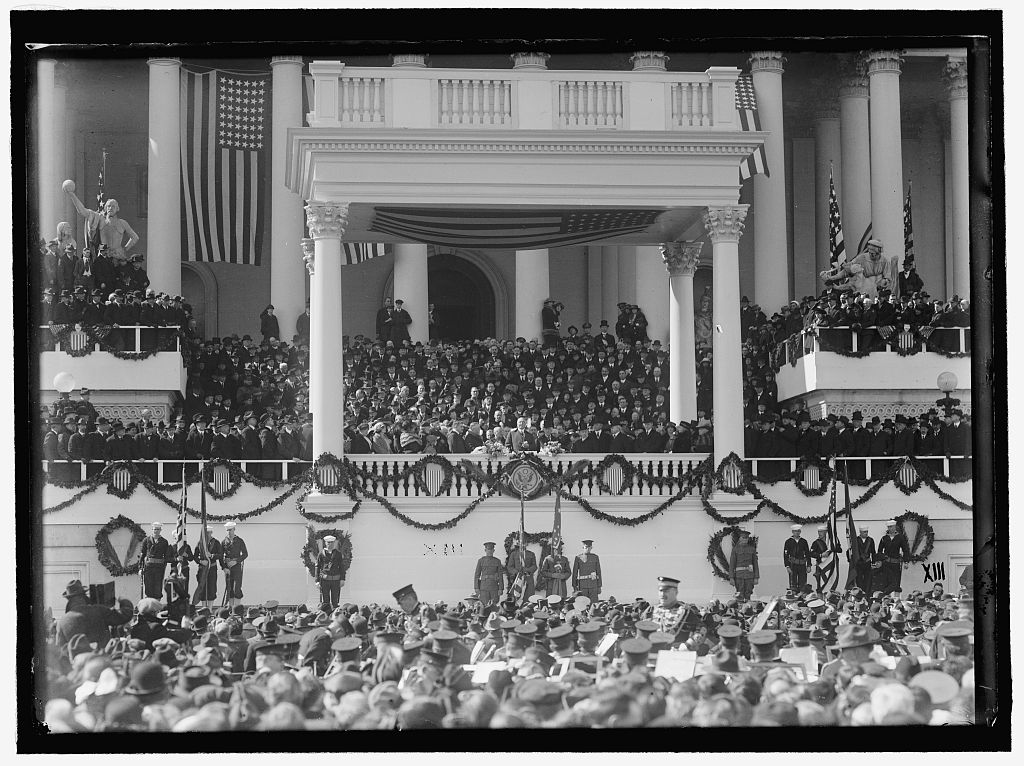

Inauguration Day, March 4, 1921. President Harding can be seen at center of the Inaugural Stand. Vice President Coolidge stands fifth in line of men in top hats to Harding’s left.

When Vice President-elect Calvin Coolidge took part in the ceremonies of March 4, 1921, the day every four years that marked Inauguration Day in this country for one hundred and forty-three years (until the Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution took effect in 1933), he came to the event an old hand to the process of ushering in new administrations. Prior to 1937, Vice Presidents were accorded their own swearing-in ceremony, yet Coolidge saw this as discordant with what should be an esteemed and seamless occasion not the disjointed one he found waiting for him on this day ninety-four years ago. His experience in Massachusetts had been ample training ground for what he would encounter in Washington and, having taken part in so many, he was certainly qualified to analyze the deficiencies of how government transitioned in the national capital. In fact, he found the pomp and circumstance of Federal ceremonies far less impressive than the dignity and respectability present throughout his own state’s inaugurations. He writes in 1929, “As I had already taken a leading part in seven inaugurations and witnessed four others in Massachusetts, the experience was not new to me, but I was struck by the lack of order and formality that prevailed. A part of the ceremony takes place in the Senate Chamber and a part on the east portico, which destroys all semblance of unity and continuity.”

President Coolidge being administered the oath four years later, 1925. The Bible lay open to one of his favorite passages, John 1, which begins: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through Him, and without Him nothing was made that was made. In Him was life, and the life was the light of men. And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not comprehend it.”

He had served in every state office save school board by this time, been inaugurated every year from 1914 through 1920, and had watched the formal installation of Governor Walsh and others during those years. It was another expression of his regard for the importance the states hold in our system that Coolidge dwells on this otherwise overlooked point. Often enough we are absorbed in affairs on the national stage and the importance of our own state and local decisions lose due proportion. We await the President’s next move while what our governors are doing or can do is discounted as somehow less worthy of significance. We neglect our local government, expecting the slack to be taken up by someone at one of those agencies in the Beltway when it was likely up to us in the first place. We look too much upon the powerlessness we feel to effect good results from Washington when we could be realizing the power we have at home, right here in our own state, within our own counties, in our own neighborhoods, and on our own streets. We must take care lest we let government continue to slip out of our grasp and become nationalized in every way. If we do not, one day we will sit shackled with the realization that we could have kept our liberties if only we had insisted decisions remain closest to the people, governance be retained in our hands and self-control starts with self.

Coolidge would go on to be suddenly inaugurated in the middle of the night on August 3, 1923, as word came of the death of President Harding. Sworn in by his own father, a notary public, he would enjoy the distinction not only of being the first on that score but also the first to be sworn in by a former President, then-currently Chief Justice William H. Taft, on this day ninety years ago. It was the practice of Chief Justices White and Taft to recite the prescribed oath in the form of a question, requiring the President to but say, “I do” in commitment to official responsibilities. It is fitting that his final public oath should be so concisely administered, as if to underscore his consciousness of what waste in all its forms costs the people. All together Coolidge took part in ten inaugurations from the Massachusetts General Court all the way to President of the United States, completing a remarkable accumulation of experiences in public service.

For now, however, Vice President Coolidge was on a road of preparation that would take him through the unprecedented attendance in Cabinet meetings, presiding over the Senate, and getting to know the country through a speaking circuit that would span from Maine to California and the Twin Cities to Charleston. It was all equipping him for that solemn night in August 1923. This is why Coolidge focused so intently upon the duties of one office at a time, that he should acquit himself faithfully in small things lest Providence entrust him with greater things. Content to end public life as a small-town Representative, his character, ability, and trust reposed in him by ever-larger electorates raised him to higher and higher obligations. Who can say what mundane and seemingly inconsequential experiences we face now are not getting us ready for something far more important?