A series of books over the last several years have taken a second look at the standards by which we measure our Presidents. The decisive bias toward Chief Executives who expanded the powers of the Office, reaching into the authority left to the Congress, the courts, the states or the people during times of war abroad or civil conflict at home has featured so largely in biographical and historical literature that no countenance is given to those who led in peacetime and prosperity. Some, like Robert Merry in Where They Stand have made an excellent points assessing our leaders based on a faith in the judgment of the electorate. Others, like Stephen Hayward in The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Presidents have reiterated the need to weigh “greatness” from the Oath they take. Still others, like Ivan Eland in Recarving Rushmore, focus on the economic health of the country as the primary gauge for Presidential quality. Alvin Felzenberg in The Leaders We Deserved (And a Few We Didn’t), appeals to a broader treatment of the character traits (or lack thereof) in each man raised from the people to lead for a time. Michael Gerhardt in The Forgotten Presidents ventures into a welcome examination of the constitutional impact and presidential lessons left by twelve of our most overlooked national leaders, from Tyler to Taft and Cleveland to Coolidge, Gerhardt relates some much-needed analysis beyond those lauded superficially as the “strong” Presidents. Each author makes important points in the ongoing conversation on what makes for Presidential greatness. These authors are challenging the preconceived notion that nothing can be learned from those who led in peaceful times. The “good times” no more indicate Presidential inactivity or weakness than do the policies of Hoover equate a “hands-off, laissez-faire” approach to government. Rather than overemphasize the merits of those who led during wartime, could it not be equally as insightful to study those who kept the nation at peace? Is it possible that the very lack of war is due to the abilities exercised by that leader at that time?

Warfare is such a prevalent condition of human nature that when peaceful conditions prevail, especially as long as they did during the eight years of the Harding and Coolidge administrations, it demands that we sit up and take notice. It cannot be merely chalked up to a global exhaustion after the Great War, though people were certainly tired of the destruction and loss. Leadership played an essential part in the restoration of peaceful terms to America, especially. It should, at the very least, warrant an inquiry into the reasons and causes of such a return of calm. The only lessons do not come from those who fail to prevent war but belong equally to those who preserve peace. It certainly takes no less wisdom or skill to navigate an entire nation clear of the rocks and shoals not merely one or two years but eight, six of which belonged to the unflappable, confident approach of Calvin Coolidge.

Any one of a series of complex issues could have ignited another powder keg of hostilities, yet they did not. Simply because they found resolution hardly means that armed conflict was not genuinely close at hand. Readily in the memories of most alive at that time, it did not take much for an entire world war to pit nation against nation again into open fighting, as had happened in 1914 after years of suspicious and inordinate preparation for peace to end, rather than investing in its continuance. During the 1920s, as America stepped into world leadership, peace could have died nearly anywhere: over war indebtedness and disarmament in Europe, over property and commercial rights in Latin America, over the inherited troubles in the Philippines or the defiant disregard for law and national obligations by those given to violent overthrow in Soviet Russia, China or Africa.

The observation on peacetime leadership by Lord Charles Fox, portrayed in the 2006 film Amazing Grace, is particularly apt here, “When people speak of great men, they think of men like Napoleon – men of violence. Rarely do they think of peaceful men. But contrast the reception they will receive when they return home from their battles. Napoleon will arrive in pomp and in power, a man who’s achieved the very summit of earthly ambition. And yet his dreams will be haunted by the oppressions of war. William Wilberforce, however, will return to his family, lay his head on his pillow and remember: the slave trade is no more.”

Once reflecting on the troubles weighing on the President’s mind, Coolidge noted, “In Washington I went to sleep pretty quickly, but if I had a hard problem on my mind, I would wake up in the middle of the night, and the tougher the problem, the earlier I waked up. Sometimes it was hard to go to sleep again. Of course, everything a President does is subjected to criticism. But I used to remind myself that the criticism probably wouldn’t bulk very large in the pages of history, and then I would reflect that the country seemed to be in pretty sound condition. So I would roll over and go to sleep.” This confident expression cannot be severed from the often serious and heavy burdens of leadership he carried with him. As he also said, “While it is wise for the President to get all the competent advice possible, final judgments are necessarily his own. No one can share with him the responsibility for them. No one can make his decisions for him. He stands at the center of things where no one else can stand.” Study reveals that peace is not an accidental outcome, that it exacts much from even prepared and experienced leaders. Leaders, by what Coolidge would credit Providence, “appear to come forward to perform a certain duty. When it is performed their work is done.” The work begun by Harding and carried to completion by Coolidge was how to “put the country in a position to liquidate the liabilities which had resulted from the war” bringing conditions from a “wartime basis” to that of peacetime.

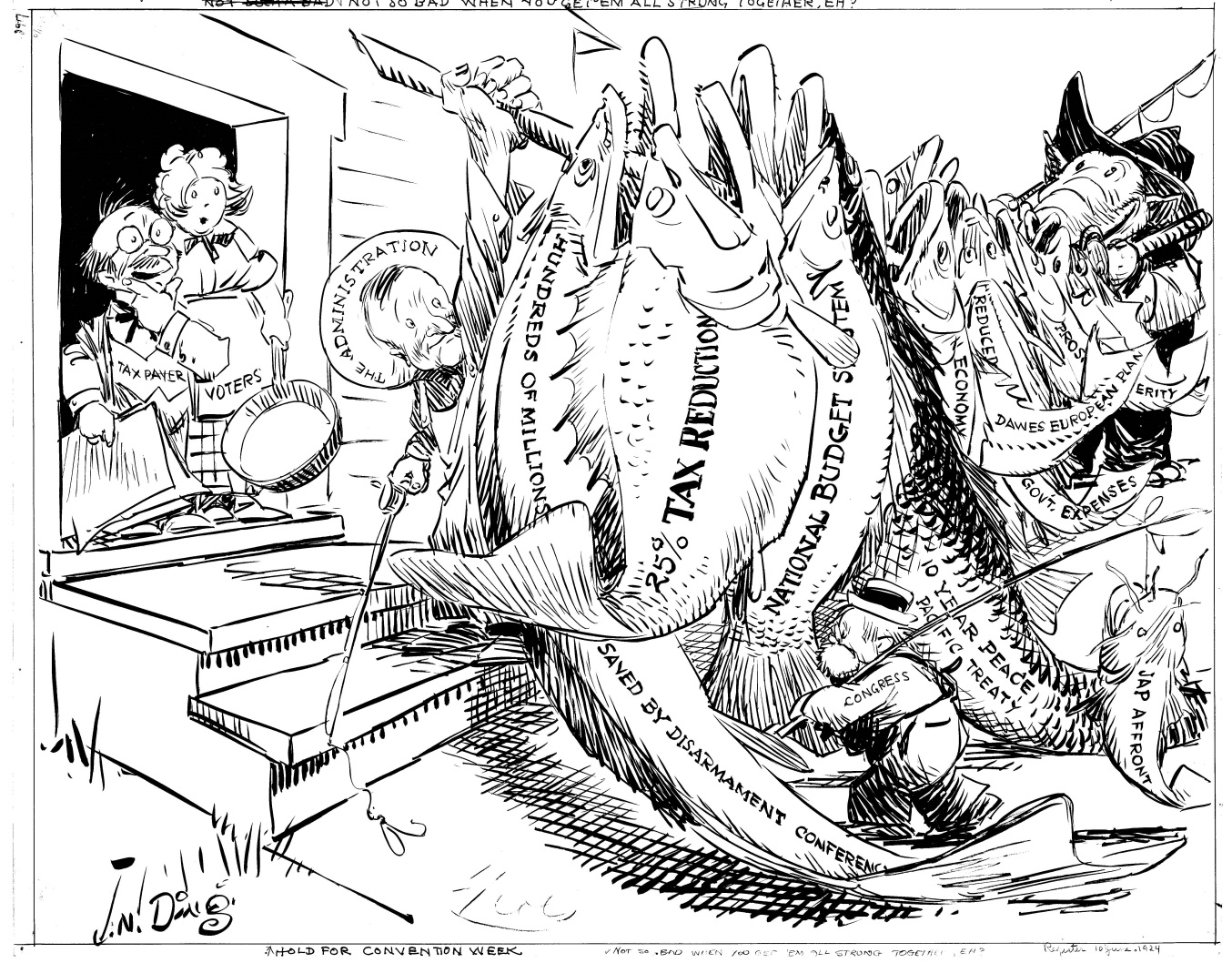

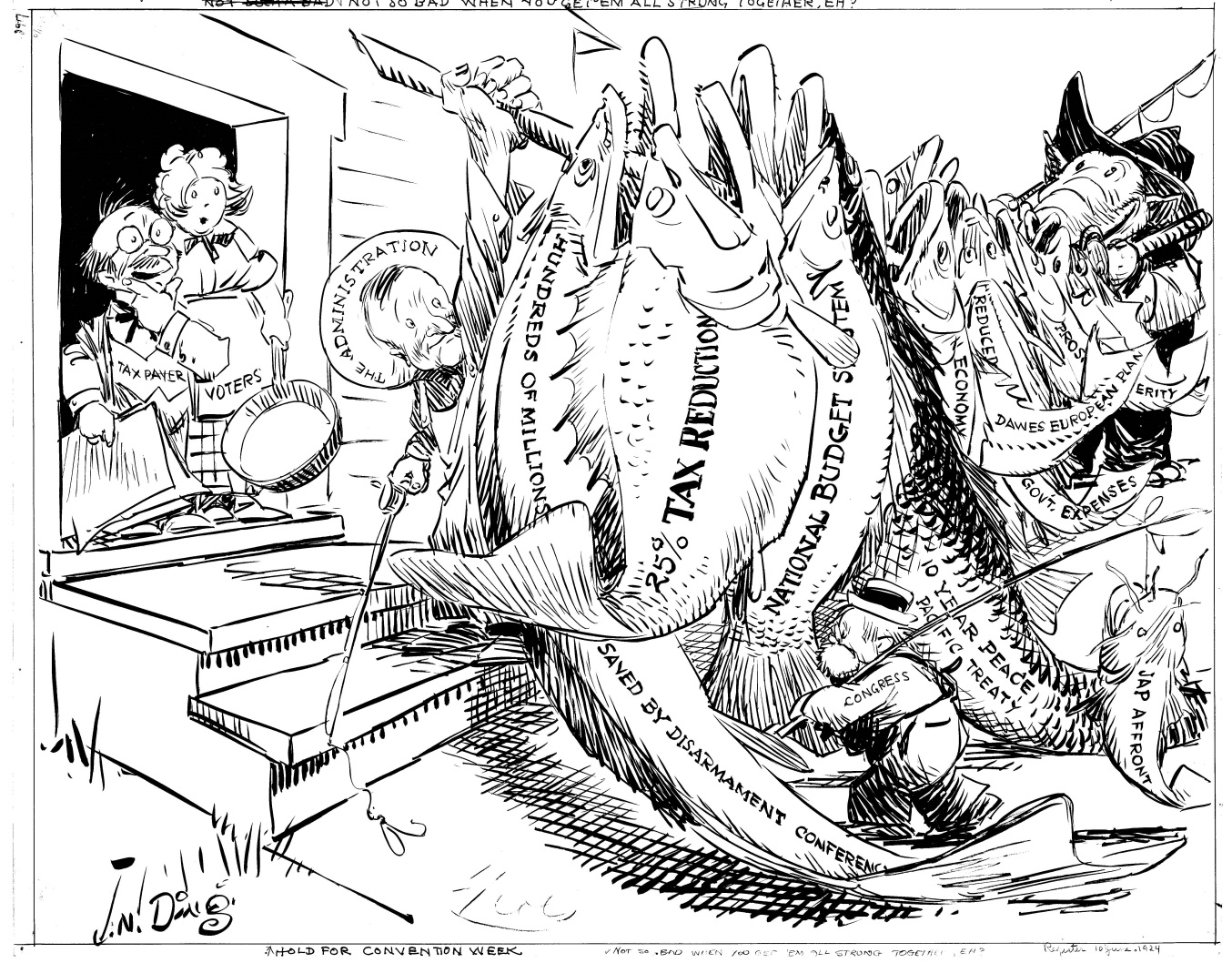

“Not so bad when you get ’em all strung together, eh?” Cartoon in the Des Moines Register by “Ding” Darling, June 10, 1924.

President Wilson, for all his dreams, had failed to craft terms of peace between the nations involved in the war. He had left America in deeper indebtedness than ever before, had fostered social and economic divisions, and had neglected his obligations here to restore calm after the storm. Blaming America for rejecting the League of Nations, Wilson retreated to obscurity leaving the unsettled problems of world war to others. It would be left for Coolidge and those he would carefully select to reclaim the environment in which Americans could flourish again, working more for themselves than for the national government, bringing calm and regularity after the social upheaval and legal arbitrariness of the war years, and finally, ushering in circumstances that would replace the reliance on great personalities in Washington. Correcting this imbalance would have to start not with material resources but by tapping into the spiritual strength which America possessed. It meant reclaiming the moral power that inspired the Declaration, gave life to the Constitution and repeatedly triumphed over every attempt to replace peace and prosperity with warfare and want.

This success, though, has not come automatically, nor through the initiative and mere force of Presidential charisma. Contrary to conventional thinking, it is to the humble and honest leader who conscientiously meets the day’s duty, goes to sleep at night having ably accomplished what was given him to do, who has done more for the peace and well-being of the country than a dozen well-intentioned Wilsons or braggadocious Roosevelts. Coolidge was one such Presidential success not because he personally furnished the “roar” of the twenties but because he respected the ideals that made it possible, continually encouraging a quiet assurance and competent faith in God and ourselves, the people in each generation who make the country work.

“There is another element, more important than all, without which there can not be the slightest hope of a permanent peace. That element lies in the heart of humanity. Unless the desire for peace be cherished there, unless this fundamental and only natural source of brotherly love be cultivated to its highest degree, all artificial efforts will be in vain. Peace will come when there is realization that only under a reign of law, based on righteousness and supported by the religious conviction of the brotherhood of man, can there be any hope of a complete and satisfying life. Parchment will fail, the sword will fail, it is only the spiritual nature of man that can be triumphant” — Calvin Coolidge, March 4, 1925.