When the first New Year’s reception opened the doors of the President’s House to the American people in 1801, the Adamses, with two months left in office, had just ushered in a quintessential expression of popular access and established custom. It lasted, with some wartime disruption, for the next one hundred thirty-one years. New Year’s Day would long continue in this country as the fitting time to make calls on friends, reconnect with neighbors, and begin the year by visiting those who ought to matter to us. For the American public, it afforded the most opportune occasion to greet the nation’s executive couple face-to-face.

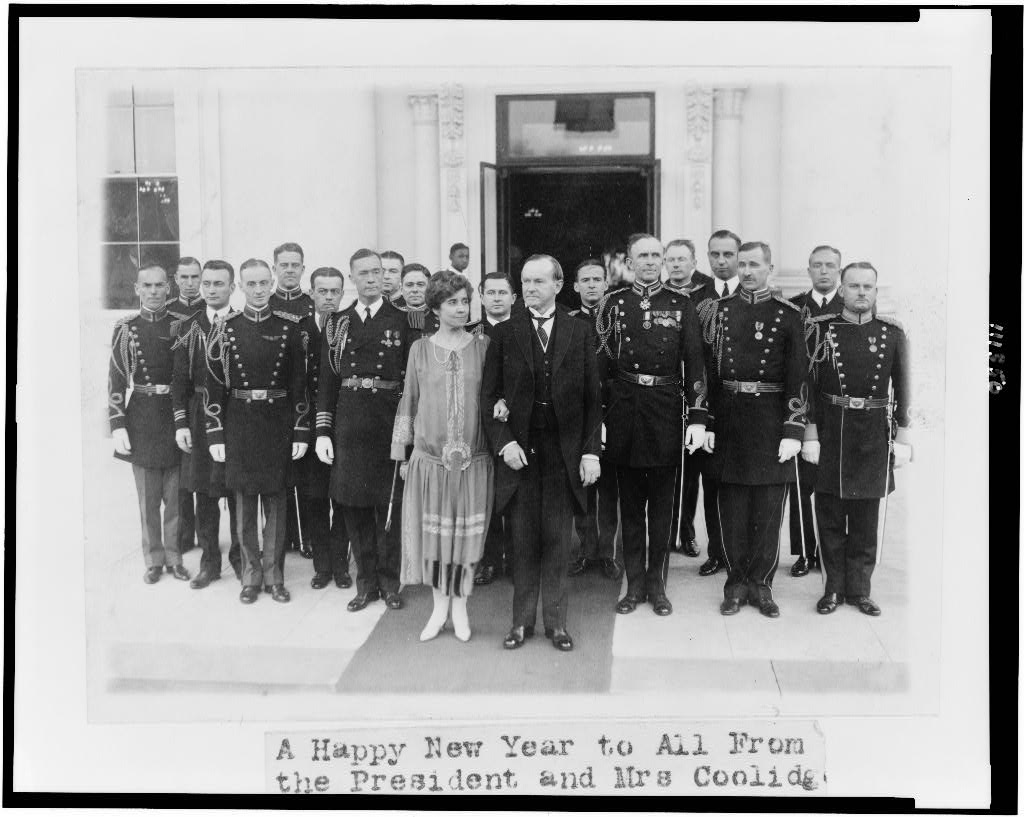

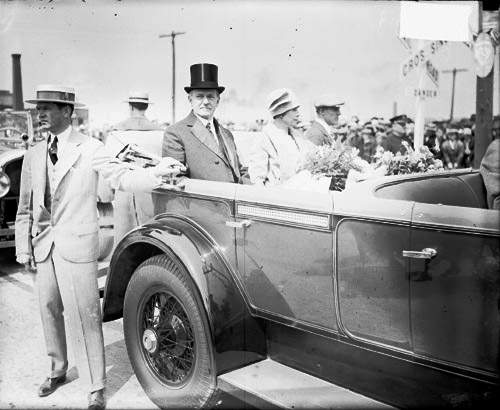

While the crowds averaged 4,000 during the Coolidge years, the President was well-acquainted with lines of 5,000 people from his days as Governor of Massachusetts. Shepherded through the historic Blue Room of the White House, the single-file lines easily continued past Executive Mansion grounds down the street along the old State, War, and Navy Department offices (today’s Eisenhower Executive Office Building) and beyond, most waiting hours for the chance to meet the President and First Lady. Calvin and Grace Coolidge were the last Presidential couple to observe this cherished tradition all six years of their tenure. The Hoovers, out of concern for economic exigencies, discontinued the reception in 1932.

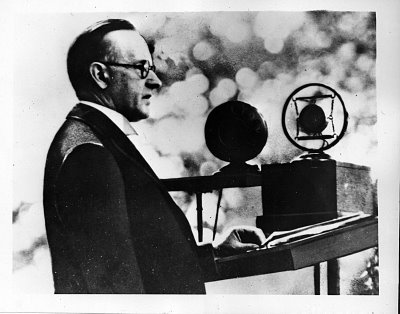

Though President Coolidge, ever the numerophile, clocked both the times and number of handshakes given at these receptions, he enjoyed the human import of what these receptions meant to so many. The 3,891 people in 1924 was the first of his statistical tallies in that category. He noted the decrease in 1927 to 3,185. Nevertheless, he was a consummate public relations professional. He understood how definitive it was to maintain more than the perception of open access to the President but also how necessary to maximize that genuinely direct approachability to as many individuals as possible. Conscious of the time others were investing in one of the most personally and institutionally vital meetings of a person’s life — the greeting of a head of state by a citizen — Cal relished when he could keep a self-important matron impatiently waiting. When official decorum permitted, he prolonged the necessarily brief visit with any of those old Civil War veterans, small town mothers, and unostentatious folks from the heartland of the nation, knowing down the line was some public official’s wife annoyed that her more important visit with the Coolidges had been postponed by even a few moments. Cal never telegraphed any of his jokes and pranks. This is what made him, for some, so hard to read. Yet, as Colonel Cheney and Captain Brown, two of the President’s military aides, witnessed at the close of one of those formal receptions: As the official couple ascended the stairs one evening to their private rooms, Cheney and Brown witnessed Coolidge elaborately bow to his lady, who returned it with an exaggerated curtsy followed by a few feigned steps of a minuet. As the officers remarked, perhaps the Coolidges enjoyed those evenings more than they let on at the time.

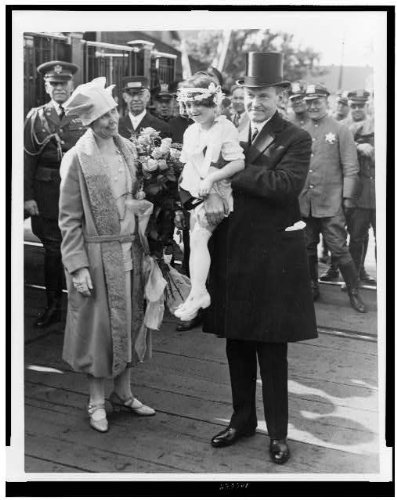

In 1924, the eighty-seven-year-old former doorkeeper of the White House, German immigrant and Civil War veteran Major Carl David Adam Loeffler, the proud father of seven children including the future Secretary of the Senate, was brought to the front of the line to be one of the first to enter the Blue Room on this day a century ago. He had served in the Quartermaster’s Department during the War, returned to civilian life, and then taken up service as doorkeeper under Grant in 1872 remaining until TR after the turn of the century. Holding a billet as doorkeeper that required salute, even by senior ranking officers, Major Loeffler passed away in 1926 at the age of ninety-one.

At the 1925 reception, President Coolidge held up the line for seventy-nine-year-old Colonel Robert Graham Scott, veteran of the 24th Iowa, who had been stationed on the Executive Mansion grounds during the War and had met Lincoln in a similar New Year’s reception in 1864. Colonel Graham lived another ten years, passing in 1935 at the age of ninety.

At the 1926 reception, the longstanding tradition of hosting the oldest citizens of the Washington, D. C. area continued with a quiet luncheon on the second floor of the White House. No less full of storied memories was New Hampshire house painter John William Hunefeld, who took his post at 9:30 in the morning to ensure he preserved his place at the head of the public line. In what came to be every year since 1924 (achieving first place in 1926, 1928, 1930, and 1931 to enter on New Year’s Day), Mr. Hunefeld became an institution in his own right. He would also be among the last on hand in 1934, waiting outside the gates to “make sure the president hadn’t changed his mind” about New Year’s Day receptions.

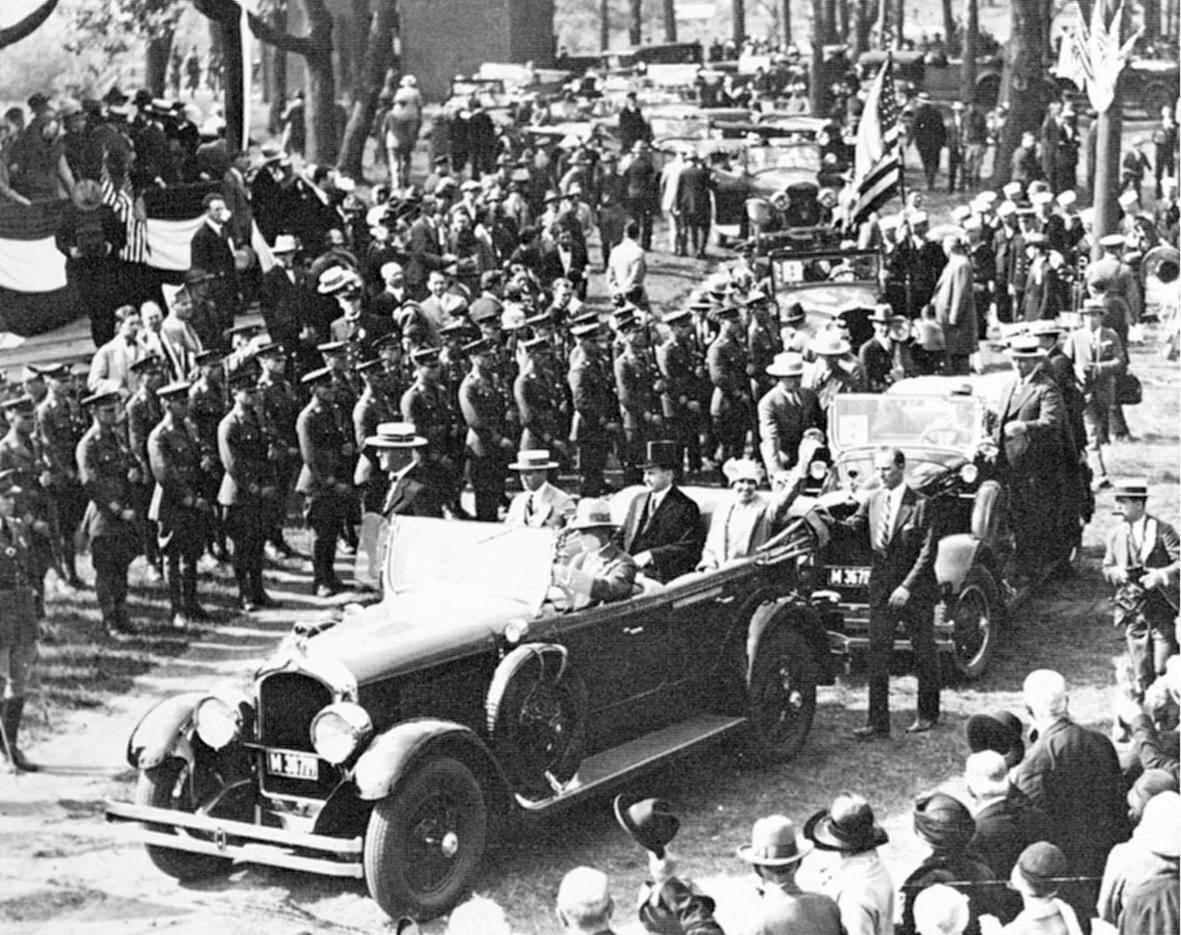

The New Year’s Day reception stood apart without comparison abroad. No equivalent head of state enjoyed such proximity to citizens. The protocol for restricted, exclusive interaction — citizens rarely even seeing their leaders outside of formal occasions – represented the norm around the world. This was true whether that leader was the Soviet chairman, the French premier, the German chancellor, the British king, or the Japanese emperor. Americans were the exception to that rule. Nor, for the Coolidges, did it entirely wait for the customary New Year’s visitations. The range of visitors between 300 to 500 persons daily became the new tradition. The Harding and Coolidge White House opened for Americans to an extent foreign to the Wilson and Hoover administrations on either side of them. It marked a sharp departure from usual custom when Harding made clear he wanted to return to an open, approachable Presidency, both symbolically and literally. However imperfect that ideal proved in practice, it became a policy the Coolidges intentionally expanded through the end of the decade.

It was true that three Presidents had been killed by assassins up to that time. That none had been perpetrated on the White House grounds was hardly cause for complacency, as the vigilant Secret Service Detail well understood. At the same time, neither was the risk of danger enough of a justification to overcome the openness due American citizens. It ran against that very principle to enclose the Executive residence inside palisaded ramparts as if it were to be a sealed citadel, behind unapproachable cordons. The greater obligation remained the ongoing access Americans deserved to their Presidents. It is regrettable that the New Year’s Day reception is now something of a distant past. Coolidge comprehended the connection of access to accountability. Insulation, both physical and institutional, would ultimately deprive the nation of a necessary avenue of civic participation, undermining the preservation and protection of popular oversight. Cutting off the ongoing involvement and investment available to all citizens, however great or small, would secure power in fewer hands who could now act unhampered by the inconveniences of representative procedures and democratic protocols.

In the interest of security, what else has been lost? What more constraints on unseen, invisible authority are citizens ready to delegate away? As Coolidge saw it, “We draw our Presidents from the people. It is a wholesome thing for them to return to the people…Although all our Presidents have had back of them a good heritage of blood, very few have been born to the purple.” He could also say at the time, “Fortunately, they are not supported at public expense after leaving office, so they are not expected to set an example encouraging to a leisure class.” Though such support is now accepted, Coolidge could freely declare that Presidents (and First Ladies) “have only the same title to nobility that belongs to all our citizens, which is the one based on achievement and character, so they need not assume superiority.”

Perhaps it is time to bring back some long neglected New Year’s Day traditions. Happy 2024!