En route back to the Homestead at Plymouth, the President and Mrs. Coolidge are reconnecting with family roots, leaving most of the artificial world of Washington behind and keeping closer to realities, where the country lives, works, worships and creates. Here rested the body of his father, recently buried in March, his youngest son, who passed two years before, his stepmother, sister and mother, surrounded by the generations who preceded them of the Coolidge family. Here was a wholesome relief from the political mentality of the District to the comfort of hearth, surrounded by the family he loved, the hills he cherished and the tasks awaiting solutions on the farm.

As much they desired to the contrary, they ceased to be “ordinary” citizens and could no longer “use the regular trains which are open to the public.” Looking back on the years, he once wrote, “While the facilities of a private car have always been offered, I think they have only been used once, when one was needed for the better comfort of Mrs. Coolidge during her illness. Although I have not been given to much travel during my term of office, it has been sufficient, so that I am convinced the government should own a private car for the use of the President when he leaves Washington. The pressure on him is so great, the responsibilities are so heavy, that it is a wise policy in order to secure his best services to provide him with such ample facilities that he will be relieved as far as possible from all physical inconveniences. It is not generally understood how much detail is involved in any journey of the President” (Autobiography pp.217-8). These intricate arrangements meant expense to the rest of the country, costs of going long distances with the Presidential retinue which made it prohibitive in Calvin’s high sense of propriety and moral obligation to the people for his office. It was not simply okay that gratuitous travel was chargeable to the public Treasury, even when prosperous times could have handled the burden. It was enough to escape from the National Capital every summer, to get away to Plymouth as often as possible and to keep other travel limited to specific destinations instead of the flagrant spending of continual cross-country tours or incessant vacations to luxurious places. It is telling that the Coolidges, who wanted to travel more, would not take that coast-to-coast trip until in retirement as private citizens again.

However, there is something more compelling than the singular dimension of a President morally committed to economy at its most practical, personal and ideal. What prompts him to support a government-owned private car for Presidential use is not to enhance official dignity, endorse government ownership in general nor is it to live grander than the hoi polloi, but it is to “secure his best services.” We have, after all, hired him to accomplish a task of leadership, we have delegated power for a limited time with specific ends, contractually obligating ourselves and the President to obtain the best within him while we exercise the best within us as citizens. It is for this reason he is compensated with such means of private travel, not to abuse it but in pouring it back into better and better public service, he is upholding the terms of that sacred agreement. By obtaining “the best of his ability” he upholds his oath to God and man and justifies the public faith entrusted to his care.

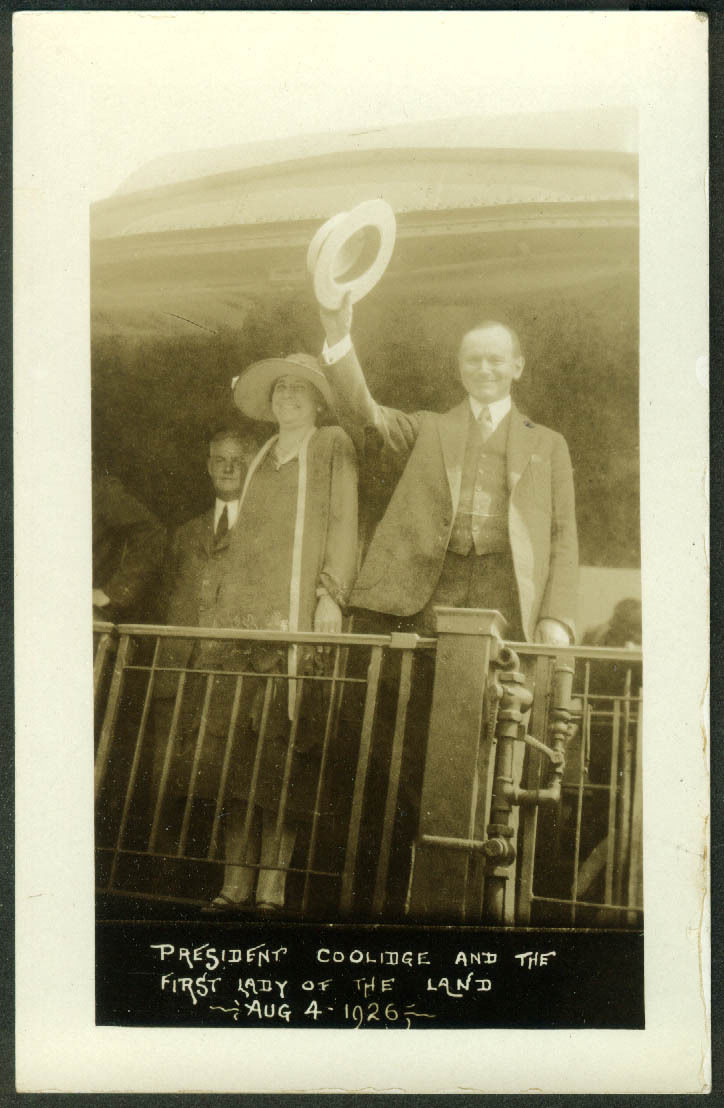

Leaving the social dramas and political flurries of Washington for the comfort of being at home surrounded by America’s people and countryside, is it any wonder that they are smiling?