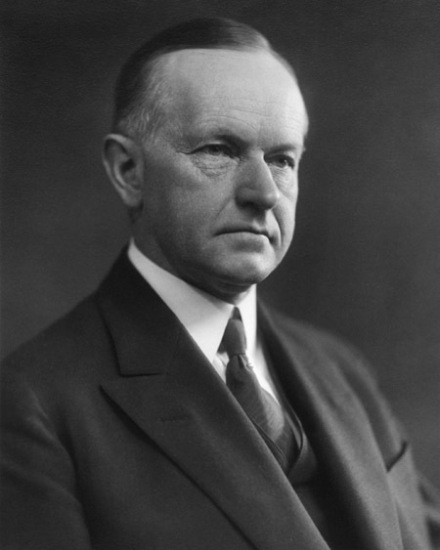

A rigorous discussion of the purpose of law does not seem to engage Americans as it once did. That is not an indicator of either intellectual progress or societal maturity. It was once a pronounced characteristic observed not merely in the halls of higher education but in the daily interaction between Americans at work and at leisure. It is rarely asked, “Is this law necessary?” or “what does this law actually accomplish?” let alone “is this truly ‘law’ at all?” The thirtieth President’s thoughts on law came through this regular pursuit of first principles, to understand things in their essential nature and design. But he also learned through the practical experiences of watching his father at work in Plymouth as its law officer and representative and later, learning from his own work as a city councilman, city solicitor, mayor and state legislator, not to mention Governor of Massachusetts. This honest search to know the nature of law did not dissipate in his approach to problems as President. It was, in fact, common for Coolidge to meet legal conflicts with the simple, yet profound, question: “What does the law say?” To him, it was inconsequential to ask what political motives were involved, whose interests would be advanced, what this or that decision would mean for his reelection prospects or those of the Party. What mattered more than anything was the authority of law upon himself and those around him. It was not for him to reshape the law into what he preferred it to be or what made him more popular with a particular demographic. It was simply, “what is the law?” He explained its success in practice, writing in 1929,

All situations that arise are likely to be simplified, and many of them completely solved, by an application of the Constitution and the law. If what they require to be done, is done, there is no opportunity for criticism, and it would be seldom that anything better could be devised. A Commission once came to me with a proposal for adopting rules to regulate the conduct of its members. As they were evenly divided, each side wished me to decide against the other. They did this because, while it is always the nature of the Commissioner to claim that he is entirely independent of the President, he would usually welcome presidential interference with any other Commissioner who does not agree with him. In this case it occurred to me that the Department of Justice should ascertain what the statute setting up this Commission required under the circumstances. A reference to the law disclosed that the Congress had specified the qualifications of the members of the Commission and that they could not by rule either enlarge or diminish the power of their individual members. So their problem was solved like many others by simply finding out what the law required (‘The Autobiography,’ pp.201-2).

Once again, the obvious is brought into focus by President Coolidge. When the calls were loudest for new rules and greater restrictions, Coolidge brought the matter back to its simplest form with that thoughtful admonition to find what the law says. As it turned out, rules already existed and the matter was resolved. All too often, the search for what the law says is missing today in the rush to legislate and regulate. In the process, not only is enforcement of existing laws neglected but the very authority of law upon all alike, including the President and his Cabinet, falls into disrepute. The question that echoes through the years is not “what do we want the law to be in this instance” or “which laws do we prefer to enforce” but “what is the law”? Once that question is answered, the next step is clear. The duty upon all, including the highest officers of the national government, is the same as it was for Coolidge, “Well, follow it.”