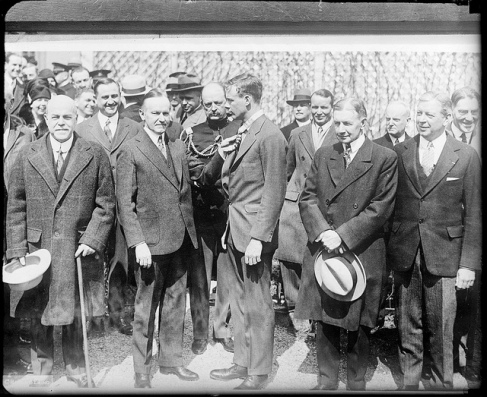

President Coolidge and his Secretary of War, Dwight Davis, were left in a difficult position in the fall of 1925. It been a difficult year for both men, from the retirement of Secretary Weeks, numerous battles with Congress and now the looming court-martial of Colonel William Mitchell. To say that the Army Air Corps officer was “outspoken” would be an understatement. In pointing out the lack of preparedness the country had for air defenses, he demonstrated a self-serving and theatrical manner that did not promote the good order and discipline most expected of commissioned officers in the military. Secretary Davis, having been a world-class tennis player (the namesake for the cup he had designed), appealed to those under his leadership on the basis of teamwork. The military, not unlike a team of athletes, has to collaborate in order to accomplish their goals. Selfish interests, however valid their grievances, must be governed with humility and self-control for the sake of others and the achievement of the mission. This fit perfectly well with President Coolidge’s ideal of service. The concepts were reflections of each other.

Yet Mitchell would continue to demand attention not for the substance of his observations but for the public to embarrass his superiors into action. Such was not in harmony with a humble attitude of teamwork and service of others. Colonel Mitchell would consequently face court-martial, five years suspension of service and loss of pay and other allowances. President Coolidge, not unsympathetic to the man’s case, would affirm Secretary Davis’ restoration of Mitchell’s allowances and half of his base pay, as Nancy Kriplen notes in her book on Mr. Davis. But this public reprimand of Mitchell would stand. The Colonel, Mitchell (as Davis had also risen to the rank of Colonel before his retirement), would turn in his resignation early the next year. Secretary Davis would accept it. Yet, neither the President nor his Secretary were averse to the preparedness of the country — such an accusation is hardly fair or accurate — nor were they stuck in old modes of thinking that refused to acknowledge air power. In fact, the spring of 1926 they would push forward the development of 52 tactical squadrons and the beginnings of an independent Air Corps signed into law by President Coolidge. The Distinguished Flying Cross would be awarded for the first time by Coolidge himself not only to the illustrious Lindbergh but also to the crew of the Pan American flight that tallied 22,000 miles in the air over a month before the better known “Spirit of St. Louis” crossing. Secretary Davis would award the Cross to Orville Wright and his brother, Wilbur (posthumously) in February 1929. It was the Coolidge administration that actively promoted the advancement of the country into modern aviation. Speaking years later of the transcontinental crossing of Costes and Bellonte from Paris to New York, the former President would reemphasize the familiar theme of service and collaboration, “Such flights are of great value in their effect on international comity. When Lindbergh made his historic voyage to Paris, the French people felt almost as much pride in his accomplishment as his own countrymen. It aroused and cemented a most wholesome sentiment of friendship…It hastens the day of good will and co-operation,” September 3, 1930.