Coolidge does not seem to have fully perceived the harm done by his youthful support for the Seventeenth Amendment, which stripped the influence of the states on the national government and removed the insulation of the Senate from the same popular impulses pressuring the House. In fact, how costly have been the consequences (in both obstructing good legislation and passing the bad) of so drastic a transformation to this unique body? The two houses of Congress were not intended by the Framers to serve the same purpose. The distinct differences between House and Senate were thrown away too hastily by those who did not thoroughly consider the costs of changing the constitutional design.

Despite his earlier support of the Senate’s alteration, Coolidge is unique among modern presidents for consistently holding a high regard for the Constitutional balance of federalism, defining a sufficient sphere of authority for the States, limiting the scope of national governance and preserving the responsibility of local decision-makers over their own affairs. By so doing, the balance of orderly liberty is kept. For Coolidge, this was more than pandering for votes. It was a necessary mechanism to ensure government remained limited especially in times of emergency. It was not to be bartered away but existed for just such occasions when the temptation was greatest to seize the reins from state or local authorities. The danger to people’s liberties was too great, even were he to exercise such powers cautiously. Coolidge knew that with the best of intentions, government would not remain limited for long even when the storm passed.

But for Coolidge, the threat of national overreach was not the only potential problem, the prospect that the States would abuse their authority was also very real. Remembering his experiences with State politics in Boston, Coolidge knew legislatures and municipalities could pass equally as reckless regulations against an individual’s freedoms. The restrictions imposed by Mayor Bloomberg of New York City and by Governor Hickenlooper of Colorado on “gun control” are but two examples of such abuses.

It was on the 150th anniversary of the Virginia Resolutions for Independence, that President Coolidge came to the College of William and Mary on May 15, 1926, summing up the value of that federalist balance with these words,

“While we ought to glory in the Union and remember that it is the source from which the States derive their chief title to fame, we must also recognize that the national administration is not and can not be adjusted to the needs of local government. It is too far away to be informed of local needs, too inaccessible to be responsive to local conditions. The States should not be induced by coercion or by favor to surrender the management of their own affairs. The Federal Government ought to resist the tendency to be loaded up with duties which the States should perform. It does not follow that because something ought to be done the National Government ought to do it. But, on the other hand, when the great body of public opinion of the Nation requires action the States ought to understand that unless they are responsive to such sentiment the national authority will be compelled to intervene. The doctrine of State rights is not a privilege to continue in wrong-doing but a privilege to be free from interference in well-doing. This Nation is bent on progress. It has determined on the policy of meting out justice between man and man. It has decided to extend the blessing of an enlightened humanity. Unless the States meet these requirements, the National Government reluctantly will be crowded into the position of enlarging its own authority at their expense. I want to see the policy adopted by the States of discharging their public functions so faithfully that instead of an extension on the part of the Federal Government there can be a contraction.”

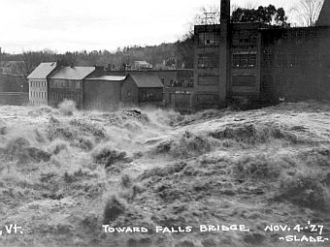

The following year would test this principle to its limits as floods would devastate first the Mississippi River Basin in April and then New England, including Coolidge’s beloved state of Vermont, in November. The damage came not only in the property destroyed but the lives lost. The most intense pressure fell on Coolidge to visit the areas, spearhead the effort to aid and rebuild and otherwise take decisive action. He deliberately held back. He dispatched Secretary Hoover to collaborate with state and local officials, not always successfully or deferentially. Those who do not understand our Constitutional system condemn Coolidge as “cold” and “unfeeling,” for his decision. They overlook the strength it took to withstand the urge to involve himself, especially when it concerned his home state. Principles mattered more. There would be no recovering the balance lost to local decision-making once he, the President, used powers he could not rightly claim. It was the burden of free people to exercise responsibilities over their lives and property, even when nature interjected. National Government was not there to spare folks from life’s consequences, however unpleasant the price.

The fight to grant flood relief would not subside quickly and while Coolidge kept much of the spending down, the drive to appropriate money, especially with an even larger surplus expected in 1928, was too much for both House and Senate to resist. Interestingly, the argument that convinced Coolidge to finally relent on a smaller relief bill was the fact that States and local governments were already paying into the sum being levied (Barry, ‘Rising Tide,’ p. 406). Federalism was working. The States and local authorities were taking responsibility for their own expenses. Had the Senate remained less constrained by public passions, as the Framers intended, it is not improbable that even the drastically reduced $296 million (which would become closer to $1 billion, in reality) flood relief measure could have been struck down before reaching the President’s desk.

The waters roaring through Springfield, Vermont in 1927

Forty foot deep floods along the waterfront of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, spring of 1927

When the levees broke and the Mississippi flooded, it is estimated some 300,000

people were displaced in as many as ten states. Coolidge would not see their

freedoms eroded further with government’s good intentions supplanting local

oversight.

“Every dollar that we carelessly waste means that their life will be so much the more meager. Every dollar that we prudently save means that their life will be so much the more abundant. Economy is idealism in its most practical form” — President Coolidge, March 4, 1925