Example is the heart of leadership. Anyone can tell someone what to do, how it should be done and what will happen when instructions are not followed. In short, anyone can be a bureaucrat. Possessing leadership is something entirely different. While it is not always, and some would say not usually, an official position, the approach of successful leaders follows the same course every time. Without a conscientious commitment to duty manifested in example, one is merely “that jerk” in the office. By throwing one’s weight around, reminding people of your authority, and refusing to put hand to the wheel and work, especially when conditions burden everyone, it only breeds resentment and exposes an utter lack of one’s qualifications to lead. Without the keen sense of moral obligation tempered with humility, even Presidents reveal their mettle.

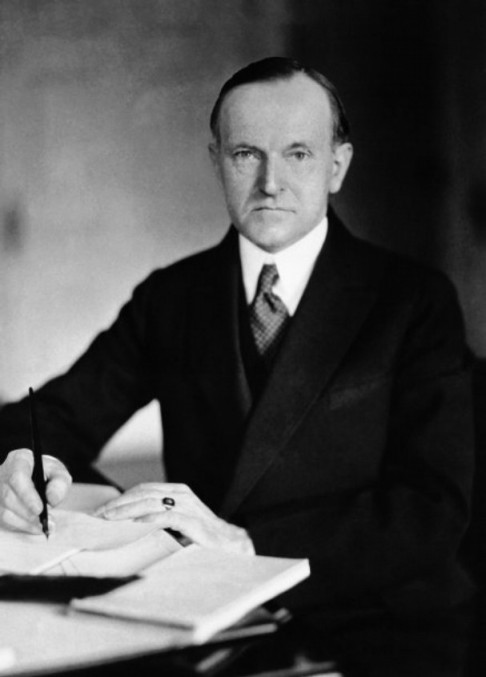

Leadership is not simply who has the most ideas, consider Herbert Hoover. Leadership is not simply who has the most amiable personality, consider Warren Harding. Leadership, especially of Chief Executives, is a profound call to serve, not be served. The inconsistency between one’s words and one’s actions could not be hidden forever and for honest leaders, such is never tolerable. For men like Coolidge, the oath and the office were serious responsibilities to be exercised with utmost respect and self-discipline. Those who lack such qualities are never able to conceal them completely from the people.

The inception of the Budget Bureau illustrates the strength of Coolidge’s leadership. The Bureau was the result of some nine years of persistent effort to bring about responsible budgeting at the national level. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, some twenty-eight consecutive years had kept balanced budgets, ensuring that government expenditures were carefully met within revenues. Surpluses defined these years and it was simply a matter of good sense to so manage the public household. That began to change with the feckless habits of the Benjamin Harrison years and when deficits hit six years in a row, from 1904-1910, something had to be done. It was President Taft who advocated replacing the piecemeal approach with a coordinated and deliberate budgeting process for all government departments. They would go through a formal system that prioritized cutting waste and practicing the strict economy it preached to others. It would be sidelined during the Wilson administration, underscoring how those considered the most “forward-thinking” today would be left in the dust by conservatives such as Taft, Harding and Coolidge, the latter being the most tenacious advocate of modern budgeting. It would be under Harding that the two Congressional bills for this concept would find effective support and quick passage into law as the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921. The Bureau found realization with Harding’s prudent selection of General Charles Dawes, as its first Director. Suitably, Dawes would serve alongside Coolidge as his bold and flamboyant Vice President.

It would be Coolidge, however, (with Bureau Director, General Herbert Mayhew Lord) who would bring both a meticulous and relentless approach to cutting down the debt and restoring surpluses. Continuing to hack away at every possible area of waste, the President, General Lord and his staff of 45 people, ensured that government spending was kept down despite constant efforts to the contrary. At the end of six straight years of surpluses, the nation’s debt had dropped to $16.9 from $22.3 billion at the beginning of Coolidge’s Presidency. Directing those growing surpluses toward productive ends became more and more difficult as Congress sought increased spending levels rather than returning those surpluses to taxpayers in the form of tax cuts, as Coolidge sought.

The Coolidge Administration, and his team of Mellon and Lord did more than talk about benefiting people with these policies, they lived them. Lord’s Bureau was proud of the fact that it used every supply until it wore out. Mellon would give $52 million of his personal income to charity, giving to people generations in the future, not including his generous gifts to the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian. Coolidge, ever conscious of his moral duty to Americans, saved much of his Presidential salary and, when his friends sought to establish his official library (before such entities were funded by public money), he gave it all to help the blind. These were leaders not by virtue of their position in government or their campaign rhetoric but by virtue of their genuine demonstration of service toward others. It is time for a renewed commitment to leadership by example.