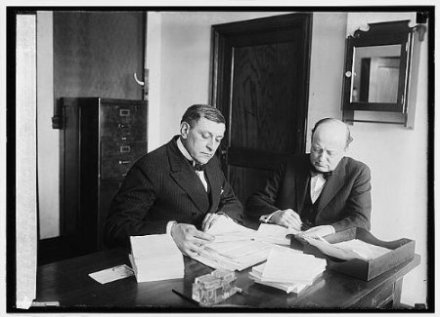

Special Counsel, Owen Roberts (left) and Atlee Pomerene (right) on the case, February 1924.

“[They] left no stone unturned to win their case. No avenue of evidence was left unexplored, and no pains or expense were spared in preparing for trial. The government’s side could not have been in more able hands. The skill with which the evidence was amassed and arranged, and the ability with which it was presented to the jury, left no possible room for adverse criticism. Messrs. Roberts and Pomerene adhered to the finest traditions of American jurisprudence throughout the preparatory and trial stages of this celebrated case; and no one who followed the case could doubt that if a verdict of guilty had been forthcoming it would have been due to the extraordinary efforts and ability of the government’s counsel” — The Washington Post, December 17, 1926, p.29

In the memories of some, special prosecutors hearken back to the days of Archibald Cox and the “Saturday Night Massacre” in 1973. Many more recall the investigation that culminated in 1999 of the Clintons by independent counsel, Kenneth Starr. As a result of that historic sequence of events the statute authorizing the office of an independent counsel, selected by the District of Columbia Court of Appeals, was allowed to expire. Consequently, it is widely regarded as an inherently dangerous and abusive office. In both occasions, the political hype and overall disruption to the country increased through the way wrongdoing in high public office was handled. The punishment for breaking the law should fall on those who commit the crime. Oftentimes, this does not happen. It tends to magnify into a frenzy of posturing, false accusations, collateral damage, denials, obstruction and a pursuit of scapegoats in the effort to avoid blame. Such is destructive to the trust the people place in their government to be responsible, fair and lawful.

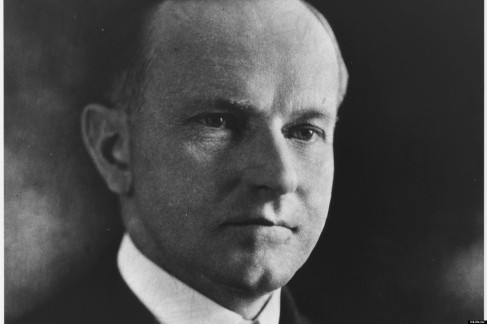

It is not to say the fault belongs with the investigators, who generally are conscientious public servants exercising their legal responsibilities to find the facts. Such was the case with the Mr. Starr. It is usually the conduct of elected officials, as well as the press, when they attempt to capitalize on either the sensationalism or help destroy an opponent’s reputation and agenda. Such attitudes were present in 1973 and again in 1999. All of these conditions were possible in 1924, yet the way the investigation of each case was conducted protected the peace of the country by upholding the fair and orderly process of law. The fact that the scandals of the Harding administration did not engulf the country anew in lasting doubt and fear is a testament to the abiding worth of integrity, sound judgment and active administration of justice. It was thanks to Coolidge that each of these qualities held firm at so early (for him) and crucial a time to keep the country at peace under the authority of law binding all, from the President to the smallest citizen.

The Senate, tipped off by constituents to possible abuses of officials in Harding’s administration, opened an official inquiry. Democrats and Progressives were swift to crow about “corruption” of big business, before any of the facts were known. The young wife of Franklin D. Roosevelt even mounted a large tea pot onto her automobile as the campaign of 1924 would begin to ramp up: the hopes of Democrats everywhere that this was the opportunity to discredit the Republican Party. As the network of connections to those suspected unfolded, however, it became obvious that both Democrats, even as illustrious as former Treasury Secretary McAdoo, and Republicans, including the popular Albert B. Fall (former Senator of New Mexico and current Secretary of the Interior) were involved. Implicating those of both parties, as Coolidge had asserted it would, the Senate quietly closed down their inquiry, deferring to the course of action mapped out by the President.

Preempting the Senate, President Coolidge acted quickly to curb both the demands for Cabinet resignations and an open-ended search for guilt that tended to characterize Congressional inquiries. He worked to restore the primacy of the law to the process, appointing a special counsel to investigate the evidence for prosecution and then direct the litigation that followed.

Some important observations emerge from how Coolidge handled the situation that would help restore the respect for law and fairness, especially in our current situation.

First, the special counsel was kept outside of the Justice Department entirely. As the accusations went public, the man who had been Harding’s closest friend was also the Attorney General of the United States. Attorney General Daugherty seemed too close to the suspects at every turn of the inquiry that he was not regarded as trustworthy with pursuing an honest investigation. Coolidge recognized that credible third parties were necessary to achieve a just result. Appointment by the President and confirmation by the Senate of the special counsel protected this credibility from the outset of the investigation. As leadership of the Justice Department transitioned to trustworthy hands first under Stone and then Sargent, greater collaboration between the special counsel and the Attorney General developed, only after this initial step to establish its credibility was demonstrated. The Attorney General was still not in charge of the case.

Second, the special counsel consisted of two men from both political parties. Owen Roberts was a Republican. Atlee Pomerene was a Democrat. Coolidge’s first duo was withdrawn when discovered they had connections to the oil companies involved. A team, as opposed to only one person, gave greater weight to the integrity and objectivity of their findings. It is already noted that Coolidge, to the ire of some, reminded antagonists that this was an apolitical issue. It was a problem that required not partisan arrogance but cooperation from everyone to suspend judgment until the facts were known. This is why the President firmly resisted all demands for the resignation of Cabinet members. He would not give in to a “lynch mob” presumption of guilt. Without evidence, short of due process, he would not be forced to give weight to the mere “seriousness of the charge” above that of actual proof. Navy Secretary Denby would resign on his own (guilty of nothing more than stupidity). Attorney General Daugherty would only be requested to resign by Coolidge when he failed to comply with a request for documents by the special counsel.

Third, the special counsel comprised two men of competent, conscientious ability. Neither man were nationally renowned lawyers nor were they specialists in public land law, but Coolidge chose them for more important reasons: they were meticulous men of character. They took their task seriously and in the end, they proved more than up to the responsibility.

Fourth, the special counsel was responsible for specific charges against the accused. The case against the accused did not proceed along an unending search for criminal activity. Malfeasance, in the form of accepting a bribe that defrauded the government, was the heart of the their work. Evidence was collected from the Senate inquiry, the Department of Justice, the Navy Department and extensive testimony of witnesses. Within a month of beginning their efforts, the evidence confirmed bribes had been accepted by the Secretary of the Interior. Indictments were issued and over the next six years the courts proceeded to hear two civil and six criminal cases involving those charged with the crime. One, Albert B. Fall, would be found guilty and sent to prison in October 1929. Another would be found in contempt of court for hiring detectives to follow the members of the jury. Still others would be acquitted by jury but the special counsel, in each case, did its job responsibly.

Fifth, the special counsel retained the cooperation of both the President and the Congress. Instead of playing political games with each new item to come to light, the special counsel team was chosen, confirmed and annual appropriations disbursed by the President from Congress. President Coolidge, from the very start, set the tone of cooperation with these outside fact finders, ensuring all was disclosed. He made clear his door remained open to any and all assistance they would require and then he got out of their way. He never intruded upon their duties, obstructed their endeavors or imposed upon the process. He made sure they had the funds designated for them to do the job, which was all he needed to do.

These observations are not locked in an outmoded time and place. They recall that political favoritism is not new. It is when government officials use their authority to reward those they prefer, be they in business or likewise in government, that the trust placed in them by the people is destroyed. Coolidge rejected this notion of rewarding certain industries or businesses with political advantages. His belief in constructive economy served for the good of everyone across the country, not just those who supported him.

These observations also recall that the special counsel can be properly deployed against crimes at the highest levels of government. A wise statesman once cleared this path and it would serve us well to reflect on its successes, not merely its failures. America will be better served when a renewed respect for law is exemplified by its leaders.

Pingback: On Dealing with Corruption in High Office | The Importance of the Obvious