Rudolph Forster, invited by President McKinley in 1897 to “help out for a few days,” stayed through eight Presidents. By Coolidge’s time, Forster was a veteran administrator. Some Presidents found the work too demanding, leaving Forster with a larger daily load. Not so with Coolidge. Forster quickly learned the thirtieth President could handle his job. Daily responsibilities did not overwhelm him as they had others. His attention to detail and conscientious efficiency ensured the work got done. Forster said, “The little fellow wades into it like Wilson…He knows what he is doing and what he wants to do. He doesn’t do anyone else’s work either. He’ll be alright at this job. He does a lot of thinking, and he looks a long way ahead.” The Office was not “too big” for Coolidge. He could “swing it.”

Not doing others’ work is important. In our system of liberty, power is specifically limited to maximize individual initiative. Coolidge would not undo that balance by expanding Presidential power, assuming duties belonging to others. He made this clear to Labor Secretary James Davis. When Davis wanted the President to read Department documents, Coolidge said, “I hired him as Secretary of Labor and if he can’t do the job I’ll get a new Secretary of Labor.” The solution was not to take on more, but to find someone who could bear his own load. After all, he said, “A President shouldn’t do too much…” A President presides.

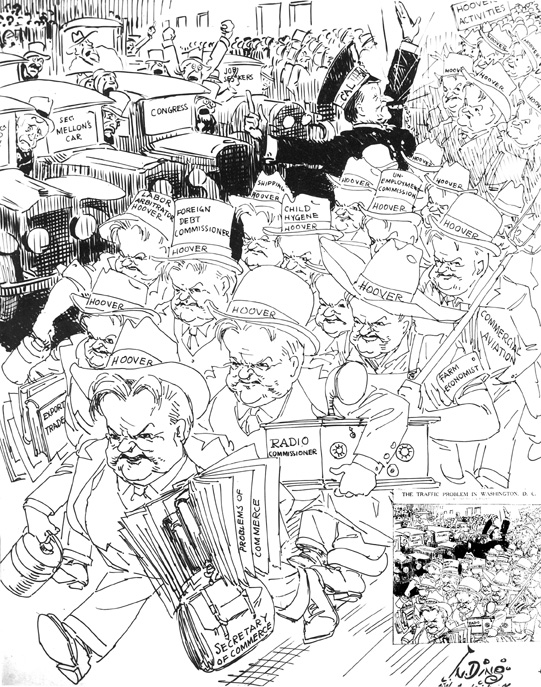

The man who followed Coolidge in the White House was a chronic interferer. Contemporaries observed that Hoover may have been Secretary of Commerce, but he was “undersecretary of everything else.” His penchant for involving himself in other department’s jurisdictions as well as state and local affairs was presumptuous at best. Hoover thought doing anything, even poorly, was better than refrained action. He contrasted sharply to Coolidge, who knew from experience that people were better equipped to solve their own problems. Writing twenty years later, Hoover would designate his predecessor a “strict legalist,” refusing to use government authority to avert the stock crash. For Hoover, Coolidge was too conscientious about the legal, and natural, limits of his job.

By holding Coolidge (and seemingly everyone else) responsible, Hoover overlooked his own role in turning normal recession into historic disaster. With liquidation prevented, wasteful uses of capital remained in the market. Ending Coolidge’s policy of constructive economy, Hoover’s spending ate away the people’s savings. By centralizing executive oversight, Hoover denied people’s ability to make their own decisions. For all his “doing,” however, Hoover was unable to fix anything. Such “fixing” is a task no one is qualified to exercise because Presidents, however intelligent and capable, simply cannot know or do it all. Coolidge understood this. Hoover did not. When Coolidge could act, he chose men, like Roy Young, who knew their specific jobs and did them without Presidential “babysitting.” Young, as Federal Reserve chair, worked to tap the brakes on speculation.

Hoover, trying to justify his own intervention, either misremembered or placed words in Coolidge’s mouth. When Coolidge spoke of economic conditions January 6, 1928, he never said speculation was “not dangerous…merely reflecting the growing wealth and power of the United States,” as Hoover claims. Knowing broad Presidential pronouncements usually inflict more harm than good, Coolidge would not speak without facts. The law gave him no authority to set market values. That task remained with the people, Congress, and the Federal Reserve. Coolidge would not pretend otherwise. Citing reports from the Treasury, Coolidge did say, “I haven’t had any indications that the amount [stock sums] was large enough to cause particularly unfavorable comment.” He used a report from Hoover’s Commerce Department to address speculation January 8, 1929. Coolidge never declared the market was “absolutely sound” and stocks “cheap at current prices,” as Hoover asserts, but said,

“I haven’t a great amount of information concerning the business situation, but I was advised this morning by the Department of Commerce that the last six months, according to their reports, was better than the first six months of the year 1928 and was up to the standard of 1927. So far as they can determine present conditions in business throughout the country are good and the prospect for the immediate future seems to be as good as usual.”

This was no glowing endorsement. There were “encouraging signs” of deregulation at first, but by 1932 a “general lack of judgment,” to which millions of people contributed, had produced depression. Solutions, true to Coolidge’s lifelong faith in the people, were never going to come by giving government more authority over our choices. Individual freedom means being allowed to fail as well as flourish. Hoover, in his ambition to manage it all, never learned what Coolidge was teaching: the greatest help a President can render is to mind his own business.