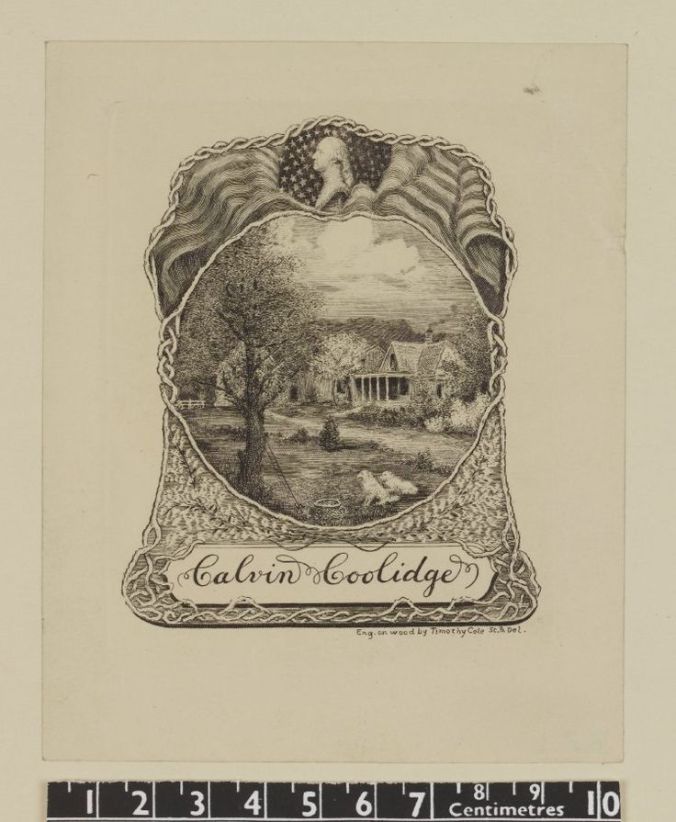

This bookplate was designed by Timothy Cole in 1929 and features an intricate bell-shaped system of roots in which is depicted the Plymouth Homestead in Vermont. The scene includes both of Coolidge’s famous white collies, Rob Roy and Prudence Prim. In the foreground, a fishing rod leans against a tree beside a basket, both accessories of his many fishing trips. The flag unfurls on either side of a portrait of George Washington, framing the simple scene above Coolidge’s name.

What a man reads and the quality of books in his library says as much as any other witness could about his character. From youth, he translated Cicero’s Pro Archia Poeta, the defense of the poet Archias’ citizenship against false accusations. As a man, he translated Dante’s Inferno from Italian. He reveled in the wisdom imparted by the great texts of civilization. In “Calvin Coolidge: At Home in Northampton,” Susan Lewis Well, the author of that excellent little book, recounts:

Coolidge read before falling asleep at night, and Grace told of the pile of books that were on his bedside table never to be disturbed. The Bible was always there plus the Letters, Lectures, and Addresses of Charles Edward Garman…and two paperback volumes of Paradise Lost. Even when traveling, Coolidge carried the two copies of Milton’s classic.

Mrs. Coolidge remembered that his library was housed in one small five-shelved oak bookcase ‘with a sateen curtain in front.’ His collection numbered about one hundred books including his college texts plus a leather-bound set of Shakespeare’s plays, three Kipling novels, and a set of Hawthorne’s works. Grace admitted that he seldom bought a book, although friends and writers gave him volumes until they numbered about five thousand by the time his presidential term was over.

The exponential growth of his library was not the only outcome due to the generosity of friends. One of the greatest of friends, Frank W. Stearns, commissioned the design of a bookplate in 1926 for Coolidge’s personal library. By 1928, Stearns had finally secured Sidney L. Smith, a renowned engraver, to complete the task. Smith drew the original work with two panels, the lower window featured the signing of the Mayflower compact in 1620 while the upper window depicted the Homestead at Plymouth. Sadly, Smith fell ill and passed away the following year before cutting the design in copper for replication.

Stearns, undeterred, approached Timothy Cole, a very successful craftsman from New York City who specialized in the almost “lost art” of wood engraving. Cole, building on the design of Smith, completed the distinct work shown above.

In a fascinating survey of the personal libraries of the Presidents, well-known collector and a devoted Antiquarian like President Coolidge, Abraham S. W. Rosenbach said this about the thirtieth president in 1934:

Calvin Coolidge will probably go down in history as one of the wisest of the Presidents. He had the reputation of being extremely cautious and I have a presentation copy of his Life, by William Allen White which seems to corroborate this statement. It bears on the fly-leaf in the President’s writing: ‘Without recourse, Calvin Coolidge.’

Characteristically, Coolidge says more in two words than most of us say in paragraphs. Employing this legal phrase, Coolidge is refusing any responsibility or endorsement of White’s work. A wise position to take, as time only makes more evident where White’s book is concerned.

Mr. Rosenbach continues, however,

Mr. Coolidge was interested in the news of the world. He read of the sale in London of the original manuscript of ‘Alice in Wonderland’ which I had purchased. On my return from abroad in May, 1928, the President asked me to lunch at the White House and to bring with me the manuscript. I found that ‘Alice in Wonderland’ was one of his favorite books, that he was interested in Shakespeare, that he liked to own good editions. He asked me details of the first publication of ‘Alice in Wonderland’ and I tried to explain to him that the first edition, issued in 1865, not being altogether to [Lewis] Carroll’s liking, was suppressed. ‘Suppressed,’ said the President, ‘I did not know there was anything off-color in Alice!’

Rosenbach wraps up his presentation on Coolidge by noting the collection the President accumulated during the White House years would find a welcome home back in Northampton, all forty cases worth (an estimated 4,000 volumes). The built-in bookcases Coolidge would discover upon moving into “The Beeches” enabled him to unpack and organize his vast collection of literary treasures. Not the relentless purchaser that President Jefferson was, Coolidge steadied his love for great books with his abiding sense of economy [from the Greek, oikonomia]. His discernment of human nature came from his grounding in classical literature. It was his informed taste combined with the generosity of friends and citizens across America that made this wise man’s library.