More than twenty years before the Supreme Court mandated desegregated schools and forty years before the Civil Rights Act, blacks and whites were already moving toward a non-segregated existence throughout the country. Moreover, sound economic principles were helping everyone to experience opportunity and the results of upward mobility in America across the entire spectrum. Blacks, finding greater opportunities “voted with their feet,” and began the “Great Migration” to the North. Wages rose in both North and South, home ownership grew 300% percent in the 1920s among blacks. Lynchings plummeted and adjustment of one’s new neighbors, rough at first, adjusted on its own — without the need for government direction of social behavior. It was the incessant social policy of the 1930s and 1940s that retarded, even erased, the progress made in previous decades.

Dr. Moton of Tuskegee Institute studied the progress of his fellow blacks in America for many years, including the Coolidge Era, and he found conditions to be moving steadily toward voluntary desegregation as well as political and economic opportunity. Freedom and equality were marching hand in hand decades before federal involvement. He observed that in sixty years since emancipation, blacks owned 22 million acres of land across the country, 600,000 homeowners (a figure which would rise throughout the remainder of the decade) and ownership of 45,000 church buildings. Blacks owned and operated over 50,000 businesses with a combined capital value of more than $150 million ($2.1 million today), including banks and other “white collar” work. There were over 60,000 in professional fields, 44,000 school teachers and 400 newspaper and media publications operated by blacks. Literacy had dropped twenty percent and would continue to improve with “Coolidge Prosperity.”

Moton would summarize, “Still the Negro race is only in the infancy of its development, so that, if anything in its history could justify the sacrifice that has been made, it is this: that a race that has exhibited such wonderful capacities for advancement should have the restrictions of bondage removed and be given the opportunity in freedom to develop its powers to the utmost, not only for itself, but for the nation and for humanity. Any race that could produce a Frederick Douglass in the midst of slavery, and a Booker Washington in the aftermath of reconstruction has a just claim to the fullest opportunity for developments.”

Writing to Dr. Moton in August 1924, Calvin Coolidge would enthusiastically commend the tangible progress made over so short a timeframe, “My dear Dr. Moton…Only a few weeks ago, I had the pleasure, at the Commencement of Howard University, of reviewing briefly and inadequately the material evidences of the progress of the coloured people…I wish to tell you of the deep impression that was made upon me by my studies of the Negro race’s achievements. In the accumulation of wealth, establishment of material independence, and the assumption of a full and honorable part in the economic life of the nation, it may fairly be said that the coloured people themselves have already substantially solved these phases of their problem. If they will but go forward along the lines of their progress in recent decades, and under such leadership as your own and many others among their excellent organizations are affording, their future will be well cared for.”

We mark the fiftieth anniversary of Dr. King’s speech on steps of the Lincoln Memorial, echoing not only the actions of Dr. Moton, who spoke there in 1922, but the faith in America to hold true to its founding ideals. It was not government to do for us, it was not the solution to give place to either despair or perpetual animosity, it was for us to return to the foundation already laid by the Framers. It is a testament to America’s virtue that Moton and King conclude their speeches with mirroring themes. America is not the problem, its ideals furnish the solution and give a conscience for fairness and justice. By aspiring to those ideals, we renew our pride as American citizens, that “fair and goodly land,” as Moton calls it. As Moton, King and Coolidge looked out over the problems and possibilities of living together a united people, they each saw the answer not in advertising the services of government to fix the human heart, not in fueling class and racial inequities but in appealing to be better than we have been by reclaiming “a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.” A dream that traces back to a shared Creator who sees beyond the externals and non-essentials to the individual’s character and soul. That dream, championed by the Founders and commended by King, Moton and Coolidge point us not to the halls of Washington for answers but to our own love for our neighbor.

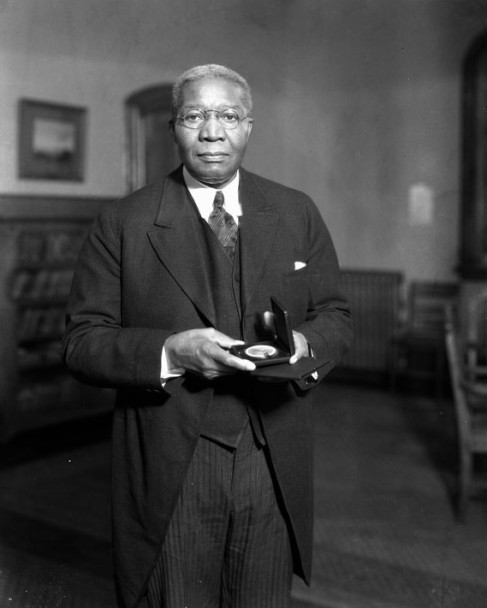

President Coolidge addressing Howard University, June 1924