“On account of the migration of large numbers into industrial centers, it has been proposed that a commission be created, composed of members from both races, to formulate a better policy for mutual understanding and confidence. Such an effort is to be commended. Everyone would rejoice in the accomplishment of the results which it seeks. But it is well to recognize that these difficulties are to a large extent local problems which must be worked out by the mutual forbearance and human kindness of each community. Such a method gives much more promise of a real remedy than outside interference” — President Coolidge, Annual Message to Congress, December 6, 1923.

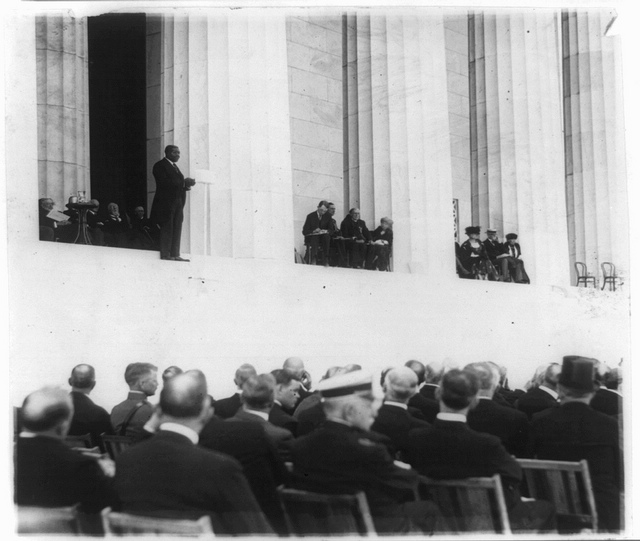

These words were not mere platitudes nor were they a white man’s effort to pander. They reinforced what Dr. Robert Moton had said the previous year on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, “This is a fair and goodly land. Much right have we, both black and white, to be proud of our achievements at home and our increasing service in all the world. In like manner, there is abundant cause for rejoicing that sectional rancours and racial antagonisms are softening more and more into mutual understanding and increasing sectional and inter-racial cooperation. But unless here at home we are willing to grant to the least and humblest citizen the full enjoyment of every constitutional privilege, our boast is but a mockery and our professions as sounding brass and a tinkling cymbal before the nations of the earth.”

When it came out that Veteran Bureau officials had hired an incompetent white woman over a better qualified candidate in the person of John H. Calhoun, graduate of Hampton Institute (Dr. Moton’s alma mater), Coolidge launched into action. He voided the Bureau’s appointments, required full retesting of the candidates through which it was discovered that not only did the woman flunk the exam but Calhoun had earned the highest score among all applicants. Despite threats to his life, Calhoun arrived safely in Washington to take up his public responsibilities. This was simply Coolidge’s way, rooted in a respect for all people. Color or race was immaterial to him. The “content of one’s character” and the competence of the individual mattered far more.

“Under our institutions success is the rule and failure is the exception. We have no better example of this than the enormous progress which is being made by the Negro race. To some of its individuals it may seem slow, toilsome, and unsatisfactory, but viewed as a whole it has been a demonstration of their patriotism and their worth. They are doing a great work in the land, and are entitled to the protection of the Constitution and the law. It is a satisfaction to observe that the crime of lynching, of which they have been so often the victims, has been greatly diminished, and I trust that any further continuation of this national shame may be prevented by law” — President Coolidge, upon accepting the Republican nomination for President, August 14, 1924.

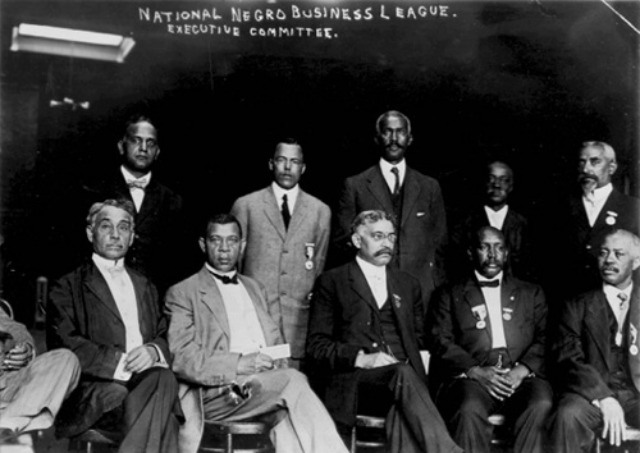

The demands to move society faster toward the ideal of co-existence on equal terms is not new. Legislation will never accomplish what is lacking in the human heart. It will ever always move as quickly as the individual’s conscience and love for others permits. It accomplishes nothing to be paralyzed by “victimhood” and refuse to embrace the responsibilities of life, the bettering of self and others through each one’s work. It was Dr. Booker T. Washington who made this clear to crowds gathered for the Atlanta Exposition on September 18, 1895, “Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life; shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem…The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than artificial forcing…It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the exercise of these privileges.” Coolidge would heartily agree, referring to Dr. Washington when he said, “His vision of the problems of the coloured people was indeed that of a seer, and…[the National Negro Business] League is one of the monuments to his life work.”

Washington and Moton, both closer to slavery than any of the self-professed “victims of white oppression” alive today, gave no place to any status as “victims” owed something from anyone — they were not victims to be coddled and pitied, they were free men who, with diligence and hard work could reap the rewards of their individual efforts in life. Nobody owed them a higher wage, a home, healthcare, affluence. These were to be earned through their own abilities. They refused to settle for less than what they knew could be accomplished by their own powers of mind, body and spirit. Welfare robs potential, they knew all too well.

What Dr. Washington termed “casting down your bucket where you are” (bettering things wherever life starts you), Dr. King addressed in “The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life,” on April 9, 1967, “What I’m saying to you this morning, my friends, even if it falls your lot to be a street sweeper, go on out and sweep streets like Michelangelo painted pictures; sweep streets like Handel and Beethoven composed music; sweep streets like Shakespeare wrote poetry; sweep streets so well that all the host of heaven and earth will have to pause and say, ‘Here lived a great street sweeper who swept his job well,’ If you can’t be a pine on the top of a hill be a scrub in the valley–but be the best little scrub on the side of the hill, Be a bush if you can’t be a tree. If you can’t be a highway just be a trail. If you can’t be the sun be a star; It isn’t by size that you win or fail–Be the best of whatever you are.”

These truths are really no different in substance than what Coolidge said to fellow Amherst graduates on February 4, 1916, “Work is not a curse, it is the prerogative of intelligence, the only means to manhood, and the measure of civilization. Savages do not work. The growth of a sentiment that despises work is an appeal from civilization to barbarism.” It is also the basis to which he appealed to labor leaders September 1, 1924, “I cannot think of anything that represents the American people as a whole so adequately as honest work. We perform different tasks, but the spirit is the same. We are proud of work and ashamed of idleness. With us there is no task which is menial, no service which is degrading. All work is ennobling and all workers are ennobled. To my mind America has but one main problem, the character of the men and women it shall produce. It is not fundamentally a Government problem, although the Government can be of a great influence in its solution. It is the real problem of the people themselves.”

The ultimate source of deliverance has never been in trusting Government to right the wrongs experienced by past generations for us but success resides in the power within our own grasp to advance from where we started to where we can be. The attempt to deny that individual exceptionalism is possible, outside of Government action — as President Obama asserted on PBS this week — closes eyes to the incredible accomplishments of men and women of all backgrounds throughout our history. These individuals, like Dr. Washington who was born on a Virginia plantation, or Coolidge, born in the exceptionally mean circumstances of rural Plymouth Notch, have built from nothing, overcame countless limitations, and left the world better for having worked and served. Segregated existence, acceptance of fixed placement in social class structure and dependence on others to fix our problems are not what bold men like Washington, Moton, King and Coolidge strove to bequeath future generations.

It is through the development of character and the application of work that betterment continues for every individual, of whatever race, color, background. It is in striving for excellence in the work each of us does that we find fulfillment and peace, not only with each other but, ultimately, with God.