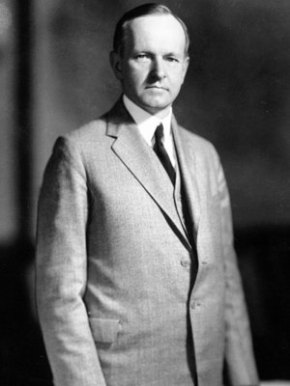

Former President Coolidge, looking back on his administration, once told Bruce Barton, “The President shouldn’t do too much. And he shouldn’t know too much.” When Barton’s curiosity was peaked, the former Chief Executive explained what he meant.

“The President can’t resign,” Mr. Coolidge answered, “If a member of the Cabinet makes a mistake and destroys his standing with the country, he can get out, or the President can ask him to get out. But if he has involved the President in the mistake, the President has to stay there to the end of his term, and to that extent the people’s faith in their Government has been diminished.”

Coolidge, never one to abide abuse of power or duty, would have seen a Presidential resignation as thwarting the people’s faith in their electoral choices and the confidence their representative system deserved. The price must be paid in a President finishing his term. The Constitution also provided for impeachment and removal but resignation was no viable “third solution” to Coolidge. The critical deficit of faith in our form of Government that followed Nixon’s resignation in 1974 is precisely what Coolidge forecast to Barton. The harm to the people, the country as a whole and the Presidential Office by Nixon’s decision, with all its attending results in subsequent years, is still being paid for in the present day. Even so, Coolidge was neither defending an absentee approach nor claiming it is okay to be an “empty suit,” oblivious to what is going on around him.

The problem, as Coolidge plainly summarized, was not in being completely unaware of what was transpiring on his watch but knowing too much. He elaborated, “I constantly said to my Cabinet: ‘There are many things you gentlemen must not tell me. If you blunder, you can leave, or I can invite you to leave. But if you draw me into all your department decisions and something goes wrong, I must stay here. And by involving me you have lowered the faith of the people in their Government.’ “

Coolidge, despite what “New Deal” writers claim, knew what was going on during his Administration, from the trivial to the consequential. He kept an ear to the ground while exercising the discipline of reserve, never volunteering that he did, in fact, know. When it became known among the ladies of Washington that Alice Roosevelt was expecting, Grace (having forgotten to ask when) was amazed to discover that Calvin already knew. When a confidential message regarding an American ambassador’s criminal conduct came across the wire, Chief Yardley, the head of that particular Bureau, learned of the document after it had already been found by Coolidge and forwarded on to the Justice Department for action outside of his office. When a letter from Lloyd George arrived addressed to Coolidge while he was staying in Plymouth for a few days in 1926, he responded to handle the situation right away without waiting to get back to Washington and reply, as he usually did, through his Secretary of State.

Coolidge remained entirely in charge of the Executive Branch. There was no doubt that he knew what was occurring in fulfillment of his responsibilities as its presiding officer. He did not do the work of his Cabinet officers or Bureau chiefs, never allowing himself to be involved in the decision-making of each department, but he knew what they were doing all the same.

When President Truman declared, “The Buck Stops Here,” he was striking upon the same principle in a different form. Whereas the President ought to know, and is ultimately responsible, it preserves the integrity of the people’s confidence in their republican system to expect that those whom the President chooses to serve as his Cabinet officers and leaders in his subordinate departments must do their work competently and faithfully. If the President has to get involved, it announces to the world that those under him are unfit and unqualified for the task. It was a sign of weakness and failure should the President have to assume the powers belonging to other officers. It brought down the high dignity of the Presidency and overturned the confidence people properly entrust to their representatives in Government to exercise efficiently and ably.

This is what Coolidge meant when he said “A President shouldn’t know too much.” President Obama, by contrast, is proudly hailed for not knowing anything about anything, as political expediency suits. It would be hard to imagine how much harm Obama could further inflict on the kind of faith Coolidge respected than he already has. It is shameful to see the destruction to our faith in America going as far as it has. Coolidge would doubtlessly look upon the current occupant in the White House with a mixture of grief and anger for the way it which the Office he strove so carefully to honor has been debased, its power to permit lawlessness excused and its responsibility on every front denied.

I am curious to find out what blog platform you are working with?

I’m experiencing some small security issues with my latest site and I would like to find something more risk-free.

Do you have any recommendations?

I use WordPress.com. It is very user-friendly, a great platform.

Hi, I do think this is a great web site. I stumbledupon it 😉

I’m going to return once again since i have book-marked it.

Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide others.

Awesome blog. I enjoyed reading your articles. This is truly a great read for me. I have bookmarked it and I am looking forward to reading new articles. Keep up the good work.