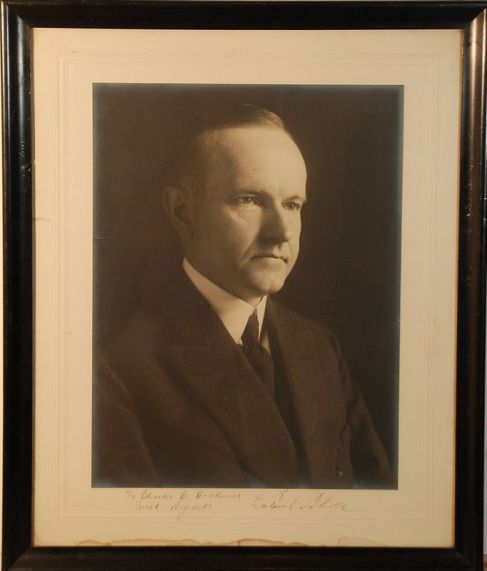

A mistaken impression can sometimes be left by historians regarding Coolidge’s attitude on civility. Some seem to think that civility is incompatible with any form of political confrontation, even employing Coolidge as the symbol of a civil discourse and non-controversial comportment. Coolidge possessed very unpopular convictions at times and made controversial stands throughout his life. His refusal to allow Boston strike leaders to return to the police force is one such example. Coolidge’s overhaul of his state’s administrative agencies, reforming 120 into 19 departments was another potential political powder keg he embraced. His adept use of the veto and appointment powers furnish more controversial examples. Instead, the “need for civility” plea, principally coming from the establishments of both parties, being the biggest violators of the rule, tend to use it in order to convince conservatives they need to sit down and quietly consent to whatever happens, for the good of the country and the Party.

A mistaken impression can sometimes be left by historians regarding Coolidge’s attitude on civility. Some seem to think that civility is incompatible with any form of political confrontation, even employing Coolidge as the symbol of a civil discourse and non-controversial comportment. Coolidge possessed very unpopular convictions at times and made controversial stands throughout his life. His refusal to allow Boston strike leaders to return to the police force is one such example. Coolidge’s overhaul of his state’s administrative agencies, reforming 120 into 19 departments was another potential political powder keg he embraced. His adept use of the veto and appointment powers furnish more controversial examples. Instead, the “need for civility” plea, principally coming from the establishments of both parties, being the biggest violators of the rule, tend to use it in order to convince conservatives they need to sit down and quietly consent to whatever happens, for the good of the country and the Party.

It is as if Coolidge never tolerated heated exchanges or passionate debate between opposing sides. In reality, he did more than that, knowing such controversy did not warrant wringing hands over the Republic’s future from the “tone” of partisan bickering. The parties were supposed to be partisan. As he once wrote, someone has to be partisan or else no one can be independent. Partisanship itself was not inherently detrimental because it was through the party system that public policy is discussed and upon which the welfare of everyone is deliberated. Partisanship could be abused, as with anything else, but it was not intrinsically one of the “deadly sins.” Sound conclusions emerge when opposing political principles are free to clash in public discussion. When government becomes too bipartisan, collaborating with unchallenged conformity, the checks and balances of our system are allowed to erode, crowding out both the well-being of all Americans and their freedom to govern themselves.

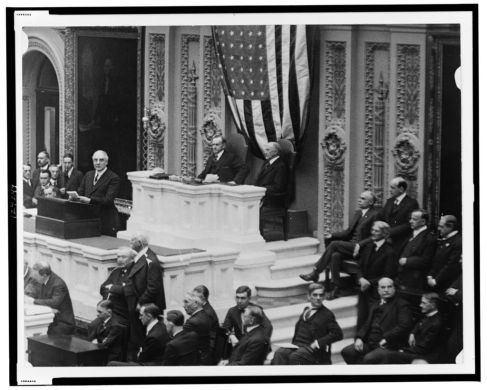

For Vice President Coolidge, during the summer of 1921, in his first few months as presiding officer of the Senate, an intense back-and-forth between Missouri Democrat James Reed and North Dakota Republican Porter McCumber unfolded before his eyes. As the political exchange turned into blunter rhetoric, accusing the other of being a “liar” and inviting his adversary to “step outside,” the visitors up in the gallery and other Senators chimed in.

Coolidge sat unfazed, calmly and collectedly, as the “coolest” tempered man in the room. Despite the growing din in the hall accompanied by the urgings of a fellow Republican to call everyone to order, Coolidge knew a use of the gavel was unnecessary. It was not detrimental to halt this “teachable moment” on the differences between party principles or to shut down the emotional banter. Both served a purpose in our system. Undiluted civility was strong enough to withstand partisan rhetoric. It could do so as long as an honest press remained free and the people were informed with the truth. It was at this moment that Coolidge gave expression to his legendary dry wit. The Vice President turned to the Republican and remarked, with the straightest of faces, “I shall, if they get excited.”