To say that President Coolidge’s speech before the American Farm Bureau Federation in 1925 was received with skepticism would be an understatement. The 5,000 people assembled in Chicago to hear what the President would say and learn what was ahead for agriculture were neither warm nor receptive. Efforts to empower government control of agriculture had already lost in 1924 despite the energetic support of Agriculture Department Secretary Henry C. Wallace. Unfortunately, Secretary Wallace died suddenly that year and the push for government-subsidized farming was defeated. Congressional support would fall short again in 1926. When the movement gained enough steam to pass, landing on the President’s desk, first in 1927 and again in 1928, Coolidge would veto both attempts for very principled reasons. His vetoes would stand while the policies he articulates here would set the course for American farmers for years to come.

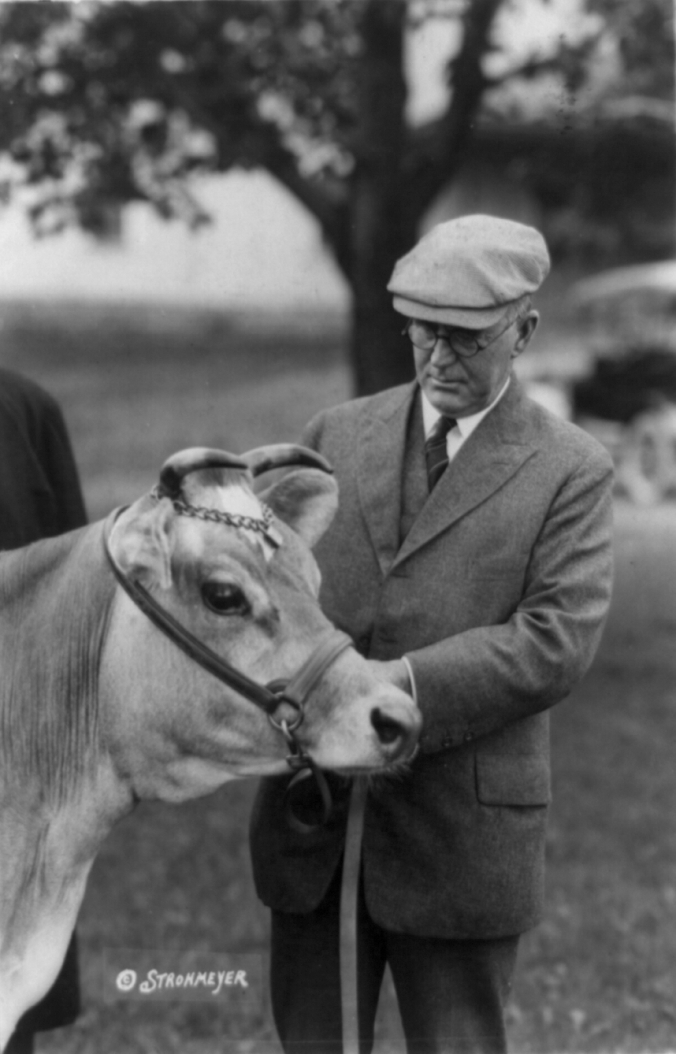

Secretary of Agriculture under Presidents Harding and Coolidge until his sudden death in 1924, Henry C. Wallace is pictured here tending to one of his Jersey cows.

Yet, long before the Congressional battles and Presidential vetoes, Coolidge stood before this gathering of farmers, ranchers, processors, advertisers, the men and women of “agribusiness” to lay out his views on the Nation’s “farming problem.” Coolidge does not receive very high marks from most historians when it comes to agriculture policy. However, the principles he explains here deserve a more honest hearing and respectful appraisal than they have been given today or enjoyed by the audience at the time.

Facing a barely subdued hostility, President Coolidge demonstrated not only his calmness under heat but also the political and personal grit for which he was known all his life. He began with a sweeping reflection on the unique and extraordinary position earned by agriculture in America. He started with praise, not criticism, for the Nation’s incredible success. It had been an incredible transformation in agriculture from what in the Old World had been “uncultured peasants” and “serfs” beholden to work land owned by the Crown. People depended on government to supply their basic subsistence. In contrast, Coolidge reminded his audience, “Agriculture holds a position in this country that it was never before able to secure anywhere else on earth.”

The preceding seventy-five years had brought agriculture to a position unknown in history. “It has become a great industrial enterprise, requiring a broad knowledge in its management, a technical skill in its labor, intricate machinery in its processes, and trained merchandising in its marketings. Agriculture in America has been raised to the rank of a profession.” Coolidge rushes to his point, again reminding his listeners that agriculture “does not draw any artificial support from industry or from Government. It rests squarely on a foundation of its own. It is independent.” Farming in America did not achieve so historic a place by government direction, determining for the individual what he will plant, how much it is worth and where it will be sold. The movement to relinquish the initiative and independent oversight exercised by the farmer would destroy the basis on which agriculture could improve.

As with any great sector of our economy, the “very eminence” of agriculture presented “increasing exactions and difficulties.” The “industry” and “ability” needed to triumph over those obstacles does not come by surrendering the precious independence of the farm to bureaucratic “expertise.” “Whatever other obstacles the American people have had to meet and overcome, of every station in life, they have never permitted themselves to be hampered by a condition of dependence.” President Coolidge, mincing no words, made plain: government controls do hamper, shackle, and restrict people at the worst possible times, when individuals need the freedom to resolve situations quickly and energetically with one’s own judgment, not as Washington slowly allows decisions on its theoretical timetable. “Unencumbered by any special artificial support,” Coolidge admonished, farmers “have stood secure on their own foundation” as opposed to the terms spelled out for them by a central command and control of production and prices. “America is not without a true nobility, but it is not supported by privilege. It rests on worth.”

It is in “our farm life” that a standard of American citizenship displays itself every day. Though diverse, agriculture like America, partakes of the “same high measure of achievement and character.” Coolidge knew firsthand that the farm was not merely in the business of producing food to eat “but as a never-failing source…from which we can always replenish the manhood and womanhood of the Nation.” This was why retaining independence, refusing to resort to government salvation, remained so crucial to Coolidge.

Government dependence exacts a heavy cost upon human life. It robs the individual of her dignity and the person of his humanity. The farm had to continue liberated from the corrosive clutches of bureaucratic stagnation. After all, it was from the same stock that the people fought for and built the country. Americans could not afford to forfeit that spirit of initiative and character. That same spirit manifested itself from Concord bridge with the “shot heard round the world” to the courageous pioneers on the Prairie down to the relentless efforts by those who furnished the supplies needed to turn “the tide for the cause of liberty in the Great War.” America’s independent and rugged farmers had been there through it all. Consequently, America’s gratitude runs deservedly deep for those who farm the land.

Whereas the Old World developed from a centralized power of government to feed and furnish its social classes, reliant on the strength of its crowded cities and affluent metropolises, America was built from its farms. “America,” after all, “never fully came under this blighting influence” of Old World norms. “It was a different type of individual that formed the great bulk of our early settlers.” Gaining results by the cultivation of the soil, the men and women who formed America were not looking to or waiting upon the permission or lordship of sprawling cities or an “industrial population.” The expansive lands, “generous” standards of ownership and technology all collaborated to make possible “here the first agricultural empire which did not rest upon an oppressed peasantry. This was a stupendous achievement.” It enabled the growth of industry and population to follow, not precede, agriculture.

Poised to become the world’s source of wheat, World War intervened and created a distorted market. Europe’s demand encouraged oversupply and inflated prices. With the end of war, consumption plummeted and prices dropped. The depression of 1920 and 1921 hit farmers — still a solid 25% of the U.S. population — harder than perhaps anyone else. Yet, where many (including much of his audience) saw cause for panic and doubt, Coolidge saw the country incrementally lifting itself out of the valley so that even agriculture was making tangible improvements. It was this review of historical experience that President Coolidge transitioned to the heart of his message: “in order that by a better understanding of the method of its progress and the position it now holds we may better comprehend its needs and better estimate what the future promises for it.”

Coolidge’s choice for Secretary of Agriculture fell to William M. Jardine of Kansas. Secretary Jardine would led the counter-charge against government price controls with cooperative marketing and individual initiative.

Coolidge knew that four years of World War could not be rolled back and prices restored to their former levels. To hope for such a return to what had been abnormal conditions was unrealistic and, ultimately, would help no one. He knew pockets of agricultural endeavors still suffered. He was no Pollyanna, especially when it came to farming because he had come from one of the most remote areas of the country, Plymouth Notch. Yet, surveying the facts and figures of agriculture as a whole, there was no question circumstances were improving since the 1921 depression. Venturing out now on emotional experiments was only going to make the situation worse, not better. Conditions were improving while one timeless truth remained unchanged: life on the farm was always going to be fraught with hardship. No law could exempt anyone from that reality. “Some people would grow poor on a mountain of gold, while others would make a good living on a rock. We can not bend our course to meet the exceptions; we must treat agriculture as a whole. and if, as whole, it can be placed in a prosperous condition the exceptions will tend to eliminate themselves.”As he would argue for in the fight for tax reduction, economic policies needed to be directed at everyone, not a favored few, if the Constitution’s limitation of Federal authority to the “general welfare” of all the people was to honored.

This annoyed his listeners, many of whom, firmly believed that those struggling farmers needed government relief to find a market for what they grew and bolster prices to maintain at least a comparable value to what had been four years prior. Not everyone needed help but those who did, including wheat and cotton farmers, ought to have compensation for the losses suffered. It was unfair that industry had seemingly recovered while agriculture, again seemingly, continued to struggle. Who better qualified to answer those calls for sympathetic help than government, they asserted? The emergency demanded authority to act before agriculture collapsed.

To that baseless forecast of farming’s dire crisis Coolidge next turned. The President had not merely read government reports thrown on his desk but he had traveled the country, met its people and seen its potential. Where some saw failure and catastrophe, the impetus for government intervention, he saw a nation ready to launch into new growth in both farming and industries. It was true that America was already transitioning from a predominantly rural people to an urban population, made possible largely by the mobility of automobile ownership, yet this was “only a part of the story.” To argue for such a drastic takeover of one-fifth of the economy, as agriculture entailed at that time, by government could not be done without fully disclosing all the facts, considering the whole story not merely one side of it. To maintain a sense of doom for agriculture, warranting government step in to save it, was itself a flawed justification, an oversimplification and a gravely short-sighted cornerstone for any public policy.

The President would then explain how, as we shall see in Part 2 of our overview of Coolidge’s address, “The Farmer and the Nation.”

Sincerely Yours,I log on to your new stuff named “On “The Farmer and the Nation,” Part 1 | The Importance of the Obvious” daily. Your writing style is witty, keep doing what you`re doing! And you can look our website about 變形金剛3.

Hi there, I enjoy readin all of your article.

I lije to write a little comment to support you.

I couldn’t refrain from commenting. Exceptionally well written!