“Personally, I do not like all this attention, but it is for the President of the United States, and I have great respect for the office” — Calvin Coolidge to his Aunt Mrs. Pollard, after boarding the Mayflower to formal salutes, the National Anthem and the ceremonious presentation of his sailing cap (Paul Boller, Presidential Diversions. Orlando: Harcourt, 2007, p.217).

“Personally, I do not like all this attention, but it is for the President of the United States, and I have great respect for the office” — Calvin Coolidge to his Aunt Mrs. Pollard, after boarding the Mayflower to formal salutes, the National Anthem and the ceremonious presentation of his sailing cap (Paul Boller, Presidential Diversions. Orlando: Harcourt, 2007, p.217).

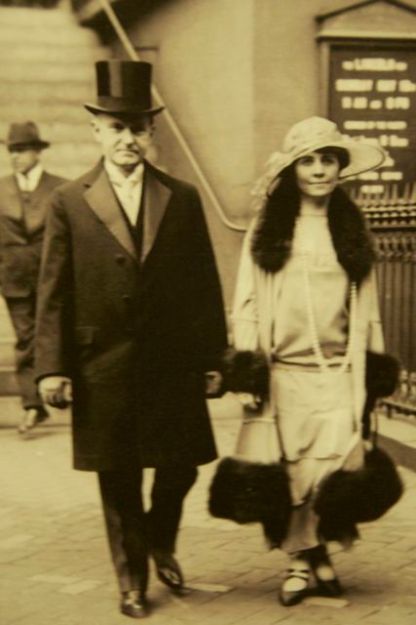

“Everything that the President does potentially at least is of such great importance that he must be constantly on guard. This applies not only to himself, but to everybody about him. Not only in all his official actions, but in all his social intercourse, and even in his recreation and repose, he is constantly watched by a multitude of eyes to determine if there is anything unusual, extraordinary, or irregular, which can be set down in praise or in blame…While such events finally sink into their proper place in history as too small for consideration, if they occur frequently they create an atmosphere of distraction that might seriously interfere with the conduct of public business which is really important” — Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography, pp.216-7.

“When the President speaks it ought to be an event” — Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography, p.219, when discussing the refusal to give speeches from the rear platforms of trains. To Coolidge, it was beneath the dignity due the Office. He had great esteem for the Presidency.

“This was I and yet not I, this was the wife of the President of the United States and she took precedence over me; my personal likes and dislikes must be subordinated to the consideration of those things which were required of her” — First Lady Grace Coolidge

“Even after passing through the presidential office, it still remains a great mystery. Why one person is selected for it and many others are rejected cannot be told. Why people respond as they do to its influence seems to be beyond inquiry. Any man who has been placed in the White House can not feel that it is the result of his own exertions or his own merit. Some power outside and beyond him becomes manifest through him. As he contemplates the workings of his office, he comes to realize with an increasing sense of humility that he is but an instrument in the hands of God” — Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography, pp.234-5.

“Young man, you are having dinner tonight with the President of the United States. You will dress properly. Go to your room and change” — President Calvin Coolidge to his son, John, after the boy had come back to the White House in casual clothes and wanted to know why, since no guests were expected outside the family, he had to dress formally and appear punctually for 7PM dinner (Robert Gilbert, The Tormented President, p.51).

Father Coolidge was not thinking of how it reflected upon him personally, he was regarding the respect due to the Presidency, an obligation equally as binding on him as upon his family. For Coolidge, the President was more than the man who occupied it at the time, it was the great and dignified responsibility of the Office. It would not be cheapened or sacrificed through any action on the part of himself or his family. This remained true all of his life, whatever office he held.

The secretary who worked in his law office, Ernestine Perry, once recounted the occasion that Lieutenant Governor Coolidge called from the train station. He was quite “disgruntled,” she remembered. It seems he had become separated from his hat and coat, arriving before them on a separate train to Northampton. As Mrs. Perry recounted, Coolidge “had only to walk the length of the platform and cross the street to his office, but he would not attempt it hatless.” To confuse this response with vanity is greatly mistaken, Coolidge held each office with the highest honor. He would not detract from it for the sake of his own convenience, sending the message that an informal appearance conveyed: flippant disregard for one’s duties. As Mrs. Perry observed, “He felt keenly that public officials should maintain the dignity of office. To him it represented the public trust. His dignity was not a pose. He was always orderly. I never saw him in need of a shave, and I never saw his hair untidy. I never saw his shoes in need of a shine” (Good Housekeeping, March 1935, p.214). It was not the appearances themselves but what the outward neglect said about the substance of the person that mattered to Coolidge.

Even his readiness to wear the gifts presented to him, despite how it made him personally appear, conformed to his high regard for the Presidential Office. Coolidge wore them not to denigrate official dignity for were he to refuse the headdress, the ten-gallon hat and chaps given to the President, it would have hurt the bond of mutual respect that must necessarily continue between the Office and the People. He could not injure so delicate a sentiment because it would impair the strength of that very legitimate connection the people rightly have to those they choose to serve as their leaders.

“It was my desire to maintain about the White House as far as possible an attitude of simplicity and not engage in anything that had an air of pretentious display. That was my conception of the great office. It carries sufficient power within itself, so that it does not require any of the outward trappings of pomp and splendor for the purpose of creating an impression. It has a dignity of its own which makes it self-sufficient. Of course, there should be proper formality, and personal relations should be conducted at all times with decorum and dignity, and in accordance with the best traditions of polite society. But there is no need of theatricals. But, however much he may deplore it, the President ceases to be an ordinary citizen” — Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography, p.217.

I adored your helpful writing. brilliant work. I hope you produce others. I will carry on watching