The logo of the National Press Club features the owl, a symbol of wisdom and vigilance, sitting alongside the oil lamp, underscoring the burn of midnight oil to faithfully report truth.

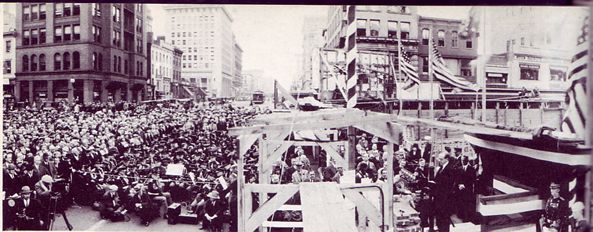

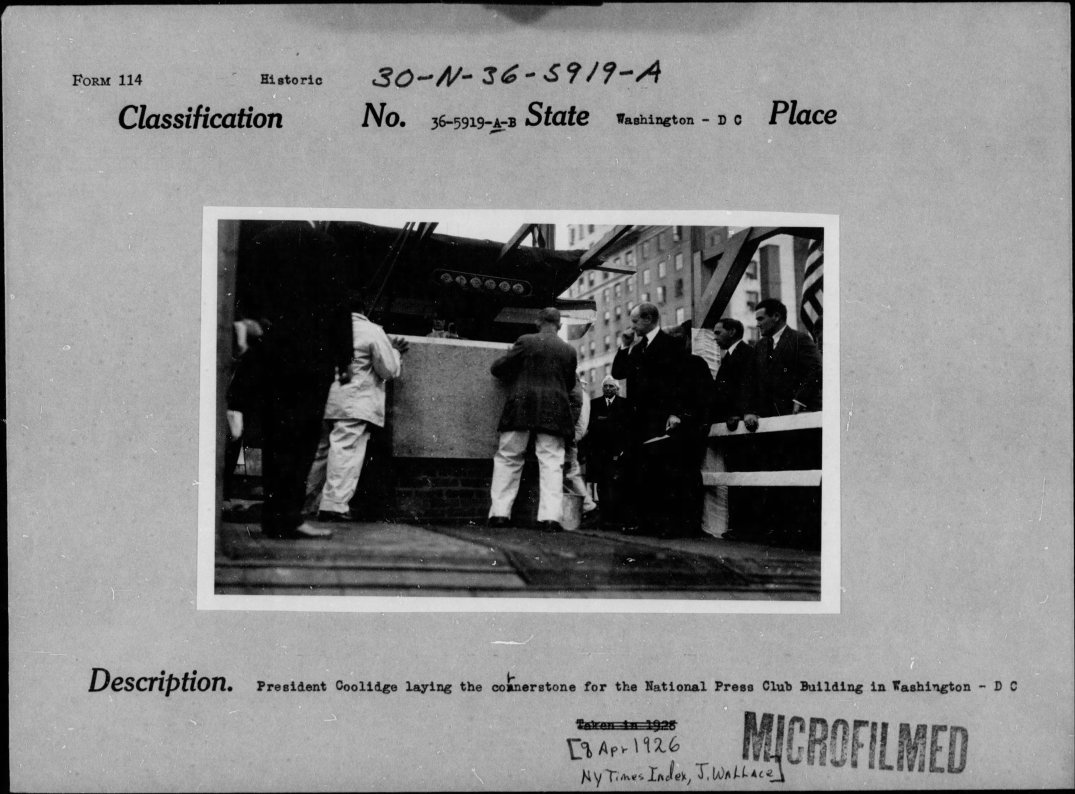

It was on this day, April 8, in 1926 that President Coolidge would dedicate the cornerstone of the new National Press Club building, which was to span the entire distance of what had been known as “Newspaper Row” from the series of news offices and print shops that once identified 14th and F Streets NW in Washington. Completed in December 1927 and dedicated anew by the President in 1928, the fourteen-story structure became the largest private office building in the entire Washington area at that time. But it all started with this remarkable cornerstone dedication. A sizable copper box was prepared to mark the occasion and was to be placed into the cornerstone Coolidge would set on this day. The box remained in the Press Club President’s vault for several more months until financial backing was confirmed to begin construction. Filled with an impressive array of objects, this time capsule included:

Uncirculated 1, 5, and 10 cent silver pieces as well as newly minted $10 and $20 gold coins donated by Secretary of the Treasury, Andrew Mellon.

A copy of each Washington daily paper from April 8, 1926.

Photographs of old “Newspaper Row,” the Ebbitt Hotel demolished to make room for the Press Club site, President Harding (the only President to also be a former newspaper editor) casting his ballot at the annual Club elections, and other memories captured by photography.

A story from the National Intelligencer recounting the formation of the first Press Club in Washington, 1867.

Another story about “Newspaper Row” with an invitation to the cornerstone dedication.

Minutes from the first meeting of the National Press Club held on March 18, 1908, Club yearbooks from 1914 and 1924, and a full membership roster from 1926.

A specially-bound and embossed Congressional Directory from the first session of the 69th Congress, produced by George H. Carter, Public Printer.

A program from the First Pan-American Congress of Journalists held in Washington, and addressed by President Coolidge that same day.

And finally, a copy of the speech delivered by President Coolidge to dedicate the cornerstone.

Make no mistake, he had something very important to say. For Calvin Coolidge, the highlight of the observance was not that he was present but something far more fundamental. The stone being dedicated was not the only one honored that day. “The press” itself, Coolidge reminded his audience, “is one of the corner stones of liberty.” After all, a central principle of our country “guarantees a full and complete freedom in the publication and distribution of the truth. The right to have a fair and complete discussion of all problems is a necessary attribute of a free people. Without it the diffusion of such knowledge as is necessary to intelligent action in both private and public affairs would be impossible. Under American institutions a corner stone which is dedicated to the press is likewise dedicated to the Republic.”

Coolidge looked out beyond the platform where he stood to a press whose strength and influence rested in its independence. The press was not entirely free from accountability, however. On the contrary, the public press is charged with very high responsibilities. He would elaborate exactly what he meant, “It is my firm conviction that the press of this country,” being so robust, independent and influential, “should seek not to cater to a supposed low and degraded public opinion, but rather create a noble and inspired public opinion.” Instead of working against what is clean and wholesome, the purpose and might of public morality, it should be harmonizing efforts with it. Rather than championing ignorance and misinformation, the press is obligated to remind people that progress continues by revealing “the development of a Divine power” at work in contemporary history. This does not omit criticism toward current events, instead it directs it to constructive ends. As Coolidge pointed out, it “is to be remembered that criticism pursued merely for the sake of criticism is a barren operation, leaving no lasting results. True journalism must go far beyond this into the field of constructive effort. It is only in that direction that there will be found anything that is of lasting public benefit.”

President Coolidge would fill out, as on a canvas, the detailed responsibilities true journalists exercise in this country. First, “liberty is derived from law.” What established and continues to preserve the freedom of the press is not the mere courtesy accorded tradition nor the conditional privilege granted by those in power, it is guaranteed in our Constitution. “If that provision were struck out from our fundamental law, the press would not remain free for an hour. As an obligation, coupled with the very greatest self-interest, the press ought always to stand as a supporter of the Constitution and as the firmest advocate of a reign of law. On that principle there should be no weakness and no wavering. It should advocate resolutely, and at all times, the observance and the enforcement of the law.”

Second, “This is all one country.” There is a proper place for pride for one’s local region. It is even justifiable and helpful but it cannot take precedence to the fact that we are one, united people. “No part of our Nation is so perfect that it can look with any disdain on the imperfections of any other part, and, conversely, all of our different areas each have sufficient advantages to commend them to respect. It is enough to know that all can say, ‘This is a part of America,’ and ‘We are Americans.’ Under our institutions all are equal.”

Third, “Americans are all privileged.” For the same reasons that logic does not sustain pitting one section of the country against another, it is equally “untenable” attempting “to array class against class. Correctly speaking, we have no sections and we have no classes. The same unity that applies to our territory applies with even more force to our population.” The press shirks one of its greatest responsibilities when it abandons this fact to see people strictly through the lens of those artificial and non-essential differences in humanity. Coolidge sides with the progressive thought of the Founders, not the reactionary prejudices of those who place Americans in the midst of some perpetual struggle between fixed classes. “When we wisely decided not to create those artificial barriers which are represented by orders of nobility, but to let true worth create for all our inhabitants a universal class, we recognized one of the great truths of human existence which can not be too often emphasized.”

The press, just like the rest of us, is to meet these challenges in human relations not by defaulting to the easy path with least resistance but by exercising the “principle of toleration.” This does not mean a double standard along partisan lines, condoning “[r]ace hatred, class feeling, religious persecution, however these may be exhibited, whether under a form of law or through the force of public opinion, or even in defiance of law.” As Coolidge would remark on another occasion, tolerance is not an assent toward evil. Tolerance “means the adoption of a broad and generous spirit under which each may work out his own destiny in accordance with his own merits.” It is the acts of intolerance – racial hatred, class prejudice, and religious persecution – that “dwarf and destroy those who permit themselves to come under the domination of these motives. Toleration is not a passive quality. It does not mean simply receiving the benefits of the tolerance of others. It is distinctly an active quality which means bestowing upon others and thereby receiving ourselves the benefits of our own tolerance.”

Where does the press fit in all of this? Coolidge answers, “No one can criticize journalistic efforts directed to the promotion of particular interests, but all that can be done without raising bitter antagonisms against other interests…Rank partisanship very quickly falls into a distortion or a complete misstatement of the facts, accompanied by arguments which lead to illogical and unsound conclusions.” Even a cursory look at history would remind us that “there has been sufficient good in both our political parties, especially when they have been in power, to require a large amount of printer’s ink in its portrayal.” While the situation in Coolidge’s time was hardly free of gross incivility and brutal partisanship, it was easier for some to “find fault with what was being done” than to “suggest what ought to be done.” Just as, in our day, it is easier to run against those in power (even if you are the ones in power) than it is to hold fast to principled solutions, taking a position that serves all Americans, not merely one party or petitioner. “It is very difficult to reconcile a narrow and bitter partisanship with real patriotism.”

President Coolidge then ventured into the great responsibilities the American press continues to carry in the field of foreign relations. Coolidge knew that most of our information of the world comes not through direct experience but in reliance upon honest reporting by the America’s journalists. To complain that the press in this country represented America “as having the best of institutions” is absurd and needless. Our institutions are what is best for us while what other countries decide to adopt is up to them. We need neither apologize for or jettison a defense of what America is and what America has done in our news coverage around the world. Racial hatreds, class resentment and religious bigotry are not only incompatible with domestic journalism, they are also inconsistent with how we treat the rest of the world. We have to appeal to higher principles than base human nature, a prejudice that had manifested itself throughout the First World War against anything German. “International friendship and good will…can not be promoted by misrepresentation and caricature of foreign people. The cultivation also of such an attitude of mind on the part of our people is an exhibition of hostility. It is sowing the seeds of war…No basis for harmony, tranquility, honorable dealing, and peace has ever been better expressed than that which is contained in the golden rule.”

Of course, Coolidge knew, there were limits to even the best of good intentions. They had to be reinforced and enacted by “proper instruments and institutions.” This is why participating in the World Court while abstaining from the League of Nations was an important and reconcilable distinction. “It is useless to love liberty unless we establish laws. It is futile to cherish justice unless we provide courts.” By insisting on reservations that safeguarded America’s sovereign rights, the universal sanctity of what is just and fair, apart from any nation’s political affairs, was advanced without embroiling the country in a countless array of foreign commitments and vague obligations. By refusing to become involved in the politics of other nations — “because they are none of our affair” — America set the scope of its participation, lending “a great influence in establishing the principle of a reign of international law” based in reason not mere military expenditures. Coolidge also knew that before a limitation of weaponry could proceed, there must first be “an intellectual and moral disarmament.” The West, thanks to President Reagan, Pope John Paul II, and Prime Minister Thatcher, accomplished this through his direct conversations with Gorbachev, insisting on ending the MAD stalemate and encouraging the expansion of glasnost. This is where the press comes in. “To create a better understanding in this direction we are almost entirely dependent on our editors and publishers. The good they can do in promoting better understanding by supporting faith and good will and peace can not be estimated.”

Coolidge could summarize without hyperbole, that “[n]o other journalists ever had a like opportunity” to perform so large a service for humanity as the American press. “In financial resources, in absolute independence, in the reaction of an enlightened public opinion to right and truth and justice, the position which they occupy in this country stands unrivaled in all history.” However, American journalism could not overlook the most important side of all in what they do, Coolidge concluded. “No enterprise can obtain a success which is worth anything unless it appeals to the spiritual nature of mankind. No matter how secular the efforts may be of a publication, it will fail of the largest attainments, will not meet the highest requirements, will not secure the widest influence unless it is moved by a reverence for religion. Our country is a reverent country and our people are a reverent people. Our institutions must rest on that foundation. The press must minister to that spirit. Their great work must go on like all other great works, in reliance upon a divine purpose. If the corner stone which we are laying to-day is to endure, it must represent these principles. ‘Except the Lord build the house, they labor in vain that build it.’ “