The Coolidges and Ambassador Dwight W. Morrow attend the International Conference of American States, December 1928

The Twenties were a decade for Pan-American, or otherwise international, conferences. Coolidge took part in no less than eight during his service in Washington. The issues of international commerce, Pan-American relations, the roll back of “dollar diplomacy” and question of tariff policy revision seemed to attract him to a degree not unlike his commitment to government economy. No one can credibly argue that the Coolidge years were isolationist in outlook or activity. He took every opportunity to personally address those gatherings of private individuals who met to discuss a host of topics from standardization, sanitation, journalism, radio, highways, trade, aviation and many more concerns. As Vice President, Coolidge spoke before the Pan-American Conference of Women sponsored by the League of Women Voters in April 1922. As President he would address the First Pan American Congress of Journalists (April 8, 1926), the Third Pan American Commercial Conference (May 3, 1927), the First International Congress of Soil Science (June 13, 1927), the opening day of the International Radiotelegraph Conference (October 4, 1927), the Sixth Pan-American Conference held in Havana, Cuba (January 16, 1928), the Pan-American Conference on Arbitration and Conciliation (December 10, 1928) and the International Civil Aeronautics Conference (December 12, 1928).

When it concerned America’s connection to the sovereign nations to our south, Coolidge was there at every turn. The Fordney-McCumber Tariff signed by President Harding in 1922, sought to return a higher ad valorem rate to the tariff system, where American-made goods were protected for their value to the markets beyond merely their quantity, size, weight or other factors. The vast majority of goods on the market, no less than sixty percent, were completely free of duties. The Tariff protected American manufacturing while keeping rates low for agricultural products and raw goods. An average 14% increase in rates protected manufacturers from inferior-quality goods flooding the markets and thereby harming both the producer, who has to raise prices to meet higher costs against a cheaper, higher quantity of products, and the consumer, who is left spending more money in the end to replace inferior goods with ones that last. The protective rates, working together with both a large decrease in taxes and reduction in Federal spending, fueled the recovery that brought America out of the 1921 depression and continued (thanks to the Coolidge insistence on economy and tax cuts of 1924, 1926 and 1928) to encourage the spread of prosperity throughout all economic tiers through the rest of the decade. Rather than remaining on course, however, the next administration dismantled the delicate balance of tariff policy up for debate at the worst time. It was the discussion to raise rates even higher in 1929, leading to the passage of a new bill, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, that unleashed an average 20% increase on dutiable imports, a 60% tax increase on over 3,000 imported products and resulted in a destructive series of retaliatory tariff increases by our trading partners around the world. Despite the firm opposition of more than 1,000 economists to the looming increases, President Hoover signed the bill into law in June 1930. While initial figures seem to indicate it was working at first, trade had collapsed and depression only deepened as a result by the spring of 1932.

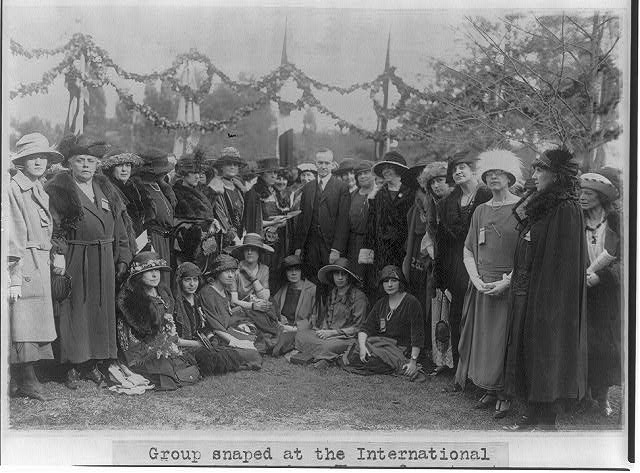

The Coolidges at the Pan American Conference of Women, Baltimore, April 28, 1922. Delegates from 21 nations took part in the gathering.

However, all this was in the future. As Coolidge took the podium to address the entrepreneurs and business men and women of North, Central and South America, imports in raw materials stood on mutually advantageous terms. As Coolidge will point out, this gathering was not a meeting of government bureaucrats and political operatives, it was a voluntary conference between private individuals exchanging ideas, seeking to better understand the needs, problems and market solutions of free peoples, sharing in the “civilizing influence of commerce.” It was not a forum of coercion presenting terms that benefited one at the expense of others with the aid of American money, military might or political deals. It was part of a the grander movement that “rests on the principle of mutual helpfulness,” which is free market capitalism as it naturally exists. Markets, free of state control, are not driven by Bentham’s mechanistic view of people as but utilitarian cogs in a system but rather fellow collaborators, willingly helping supply and be supplied with what each individual needs.

Coolidge commended this gathering of minds and talents from across our Hemisphere for its true merit which lay “in the fact that it represents not government but private industry.” After all, governments do not create, people engaged in commercial relationships do. “Governments do not have commercial relations. They can promote and encourage it, but it is distinctly the business of the people themselves. If this desirable activity is to grow and prosper, if it is to provide the different nations with the means of self-realization, of education, progress, and enlightenment, it must in general be the product of private initiative.” Keenly aware of the political discontent to the south coupled with a clearly harmonious relationship then existing between Pan-American suppliers and U.S. manufacturers, Coolidge continued, “Under free governments trade must be free, and to be of permanent value it ought to be independent. Under our standard we do not expect the Government to support trade; we expect trade to support the Government. An emergency or national defense may require some different treatment, but under normal conditions trade should rely on its own resources, and should therefore belong to the province of private enterprise.”

The Coolidges in worship services en route to Havana to attend the Sixth Pan American Conference, January 1928. They can be seen seated on the front row to the right on the deck of the USS Texas.

That policy, which lifted America out of depression in 1921 and since 1913 had raised it as the foremost market for Central and South American raw goods, from wood and copper to cane sugar, coffee and food stuffs, was yielding benefits overwhelmingly in favor of our neighbors to the south. If there was any dominant partner, it was South and Central America, who held nearly all of our money in unprocessed materials. The dependence on Europe for a market had decisively changed. Now the United States was buying more in the markets of Central and South America than it was selling. The clear beneficiary was the collection of American Republics south of the Rio Grande. This was not an unsettling or harmful development, in Coolidge’s judgment. It was a definitive good and a proof that markets, allowed freedom within marginal tariff rates on a small portion of goods, are mutually advantageous to all participants. “It is our conclusion that while government should encourage international trade and provide agencies for investigating and reporting conditions, those who are actually engaged in the transaction of business must necessarily make their own contacts and establish their own markets. There is scarcely any nation that is sufficient unto itself. The convenience and necessity of one people inevitably are served by the natural resources, climatic conditions, skill, and creative power of other peoples. This is the sound basis of international trade. This diversity of production makes it possible for one country to exchange its commodities for those of another country to the mutual advantage of both. It is this element that gives stability and permanence to foreign commerce. It contributes to satisfying wants and needs, and so becomes help to all who are engaged in it.”

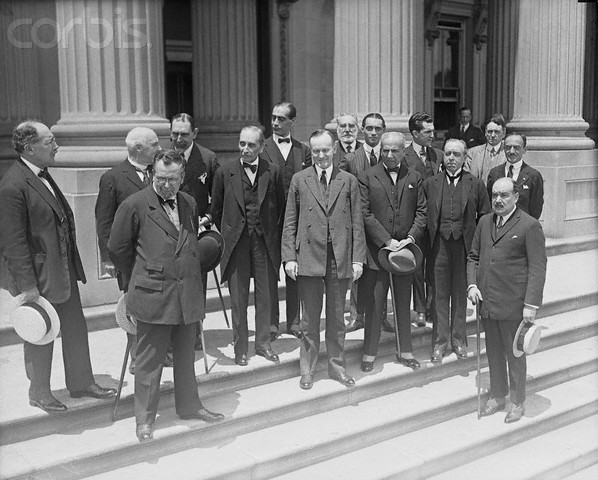

Vice President Coolidge entertains South American delegates to the Chile-Peru conferences then in session at Washington, June 1, 1922.

Coolidge did not merely praise the broad outlines of growth and commercial collaboration between the Americas, he lauded the specific directions it was taking in the development of transportation, improving the speed the travel by ship, rail, road and air. Coolidge complimented the great network of exchange not only for its material improvement but especially for its conveyance of ideas, its sharing of information, education and communication, embodied in the cable and radio, the Pan American postal agreement, the opening of roads and the clearing of new commercial horizons that resulted. In short, this meant a “more abundant life for all concerned,” not only materially but spiritually.

As he closed his remarks to these market pioneers and creative adventurers from across the Western Hemisphere, Coolidge came back to the intangible importance of what this movement meant. “It is this mutual interdependence which justifies the whole Pan American movement. it is an ardent and sincere desire to do good, one to another. Our associates in the Pan American Union all stand on an absolute equality with us. It is the often declared and established policy of this Government to use its resources not to burden them but to assist them; not control them but to cooperate with them. It is the forces of sound thinking, sound government, and sound economics which hold the only hope of real progress, real freedom, and real prosperity for the masses of the people, that need the constantly combined efforts of all the enlightened forces of society. Our first duty is to secure these results at home, but an almost equal obligation requires us to exert our moral influence to assist all peoples of the Pan American Union to provide similar agencies for themselves. Our Pan American Union is creating a new civilization in these Western Republics, representative of all that is best in the history of the Old World. We must all cooperate in its advancement through mutual helpfulness, mutual confidence, and mutual forbearance.”

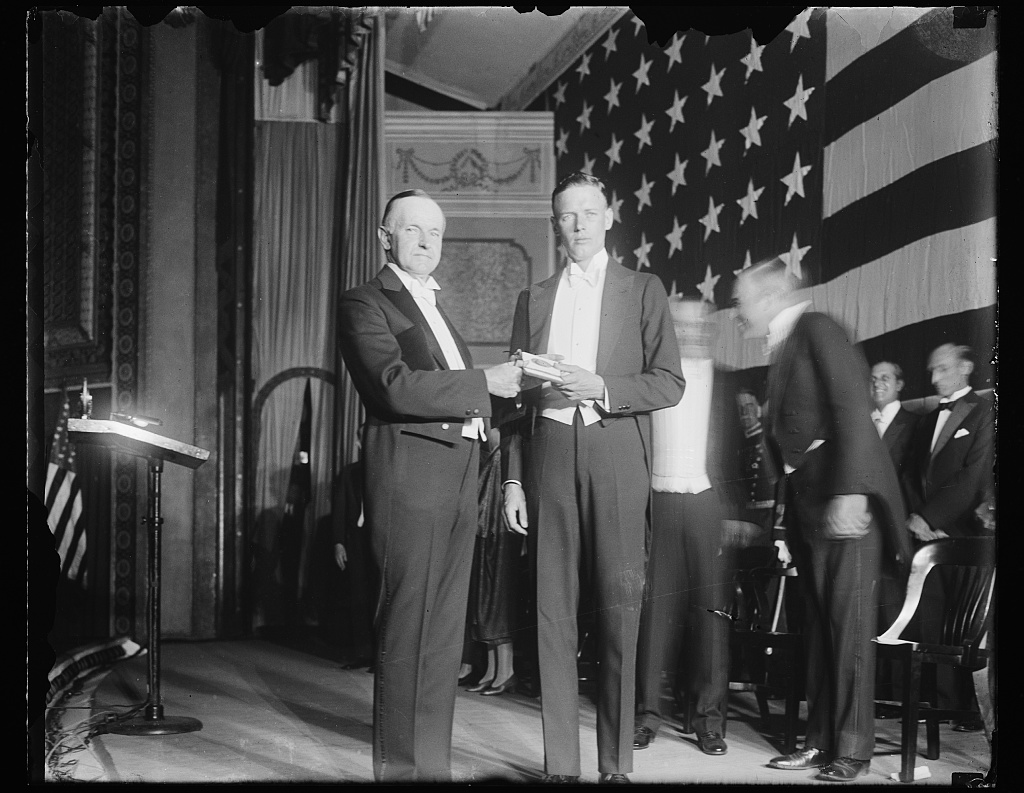

Calvin Coolidge and Charles Lindbergh, November 1927. Lindbergh was virtually conscripted as an ambassador of good will to Latin America, on an even grander scale than the pilots of the Pan-American Goodwill flight of 1926. The diplomatic campaign, on the “wings” of Lindbergh’s remarkable solo crossing of the Atlantic that summer, did much to advance Latin American relations. Lindbergh would also meet his future wife, Anne Morrow, as a result of his unwitting venture into diplomacy by airplane.