While this source parrots much the same accepted narrative for Coolidge’s supposed “do nothing” time in the White House, these numbers comprise part of a sizable record contradicting that biased claim, shattering much of the shallow veneer plastered up against the Coolidge Era for far too long by New Deal “historians” like Art Schlesinger, William Leuchtenburg and those who echo their assumptions. http://us-presidents.findthebest.com/l/12/Calvin-Coolidge.

This month, like January, held a special place during the Coolidge years. It was the continuance of a tradition begun under Harding but abruptly ended with his successor, Hoover. It would come to carry the resolute Vermonter’s unique imprint on its importance to transparent and sound government. It was the bi-annual meeting for the Business Organization of the Government. Held for eight years in various auditoriums around Washington, from the Interior Department offices to the Continental Hall, Coolidge would take part in no less than ten such gatherings.

The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, shepherded to passage by Harding and its first Director, General Charles G. Dawes, brought what had been an arbitrary and chaotic budget process to order. Some years would see more than twelve competing budgetary packages presented to the Congress from the various bureaus, departments and agencies in Washington. Requests would often be made for the same appropriated amounts, with Congress left to sort out and streamline the tangled mess. The Budget Act changed all of that, restoring authority for Executive Branch responsibilities to the President. Now it was through the Chief Executive that all Cabinet heads and bureau chiefs had to request their respective budgeted funds, not the Congress. It served to reaffirm the Constitution’s separation of powers but also to put the brakes on a random exchange of favors and hold the Federal Government to the discipline of time-tested household budgeting. Harding and Director Dawes would lead the first meeting on June 29, 1921. As Harding’s momentum slowed, it would fall to Coolidge, even as Vice President, to present the case for what would come to be called “scientific economy.” It would be the preparation of Calvin Coolidge that particularly qualified him more than any of his contemporaries in the White House to exercise the necessary perseverance to follow-through with a consistent restraint of Congressional spending on one side and Executive regulation on the other.

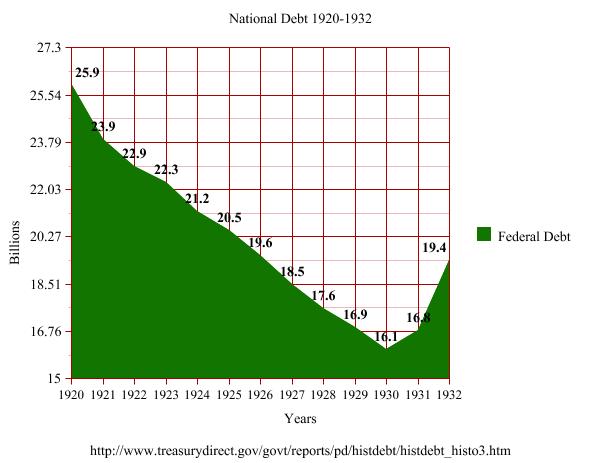

Graph encompasses the final year of President Wilson through the third year of President Hoover. Notice the consistent retirement of debt each year of the Harding and Coolidge administrations. It was so strong a system that it carried forward into Hoover’s first year, until spending resumed its climb from 1930 onward.

Unlike many of his peers however, his accomplishments did not end with rhetoric. He practiced what he preached, holding firm grasp on the White House staff budget, a duty he viewed as under his own personal purview. He left office having saved most of his $75,000 annual paycheck. He achieved what so many, even the great Ronald Reagan, failed to do: actually reduce Federal spending while paying down the nation’s debt from $25.9 to $16.9 billion in six years. He did so not by “wheeling and dealing” with the very recalcitrant Republican Congress of his day, but by winning their respect with his honesty, political experience and courage. He did not flinch when lesser men did. While he left many wondering at how he was able to co-opt allies and neutralize opponents, he never exchanged what was right for everyone in place of personal electoral advantage. In this way he proved successful in anticipating what Congress would see and do, as Dawes later noted of him, better than the House and Senate themselves most of the time. Yet, Hoover, in part because of his refusal to recognize Congress’ role as legitimate, would see his work frustrated and his goals repeatedly redirected. On the other hand, it was Coolidge’s fairness, good sense and integrity that equipped him to overcome each challenge and keep the agenda moving.

Coolidge made it plain in his Autobiography that he refused to take reprisals or exert coercion on those who disagreed with him (p.232). He simply exercised his responsibilities justly and impartially, keeping his door open to everyone. If they passed disagreeable legislation, he had the veto, which was used fifty times during his tenure. He hardly operated alone, appointing able men like C. Bascom Slemp and Everett Sanders, former Congressmen, who knew the political topography like few did. He also had the determined General Lord, whom he consistently backed with each decision to cut, eliminate and chip away at Washington’s wasteful expenditures. When the issue, no less contentious than now, concerned budgeting and taxes, he was particularly apt at taking his reasons directly to the American people on these two grand occasions each January and June, letting them see and especially hear the logic behind and importance of “scientific economy.”

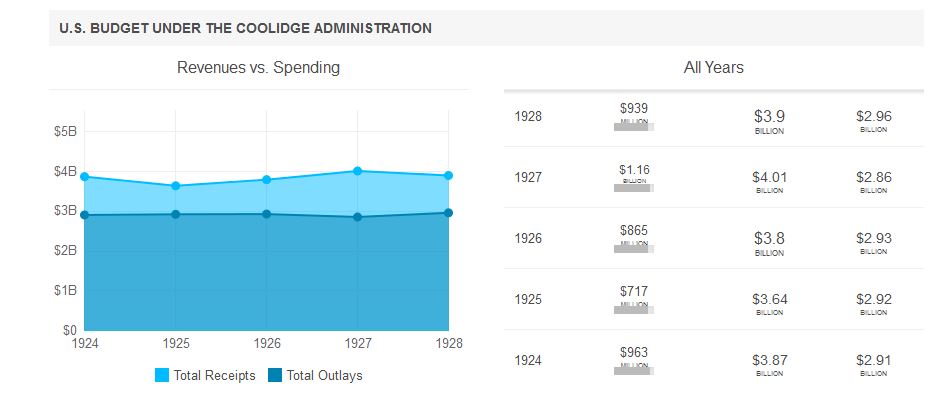

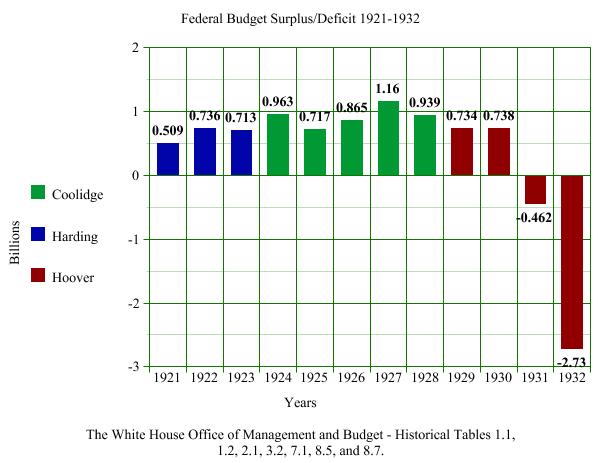

A look at the Federal Budget Surpluses and Deficit totals from Harding through Hoover after the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921. Coolidge maintained healthy surpluses all six years of his tenure. It was Hoover who ended that achievement and suspended the bi-annual meeting of the Business Organization of the Government.

In the coming weeks, we will showcase some of the highlights of the ten speeches he made before the Business Organization of the Government as President, most of which were carried over the radio for millions of Americans to listen in for the first time. Marshaling his talent for this new medium combined with a very genuine passion for strict economy, Coolidge even infused a strong sense of dramatic flare to make his case directly to us. In this impressive fusion of salesmanship and substance, it marked an incredible time in American history when none less than the President of the United States championed good governance and constructive economy.