When a young man named Ronald Reagan stepped up to the podium on October 27, 1964, to deliver the now-renowned “A Time For Choosing” speech on behalf of conservative Presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, among the many fundamental points he made was the timeless challenge for government to actually “read the score to us once in a while.” By 1964, the country had experienced thirty years of justifications for redundant and ineffectual government programs yet an occasion to assess progress, determine results and eliminate failure never happened. Plans and initiatives never went away, they only increased, without a thought to whether any of them were effectively producing what they were intended to accomplish or simply making conditions worse than before. Having been a sports announcer in his WHO days, Reagan was making the case for what his predecessor, Calvin Coolidge, actually accomplished through the bi-annual meeting of the Business Organization of the Government. Coolidge did more than talk, he read the “score” of how our government was doing with our money. On nationwide radio hookup, Coolidge would review America’s balance sheet of receipts and expenditures, eying where improvement was needed, commending thrift, correcting wasteful habits and making his argument directly before those listening around the country to keep government on a business basis.

When the assembly of Cabinet heads, bureau chiefs, and agency directors met with the President and General Lord for its sixth meeting on January 21, 1924, the country had seen two and a half years of results from the Budget and Accounting Act. The central question was this: Should we keep going with a business administration of our Nation’s affairs or is there another way? As Coolidge would argue, the enormous good accomplished under these standards demanded persistence, refusing to allow a relapse to government as usual. The results obtained were reaching not just the top tier of Americans but raising the entire economic spectrum, improving the lives of the whole people, not merely a favored few. Coolidge knew this meeting, prone to all the form and facade of any government collaboration, was unprecedented. “It was a new kind of meeting,” Coolidge reminded his audience. Begun by Harding, his predecessor, Coolidge did more than continue it as another token tradition, he took up the heavy lifting of a relentless advocate and unwavering champion for keeping government within its means, accountable for its spending and faithful to its public trust.

Without the extraordinary leadership of Harding and then Coolidge, who cemented the Business Organization meeting as a fixture throughout his six years in office, the discordant pressures in Congress and his own Executive Branch would have quickly unraveled what work had been started, sidestepped the law, overwhelmed the President’s policy and turned every surplus into deeper and deeper deficits. There would have been no Roaring Twenties without these two Presidents bravely and consistently holding government to essential business practices.

The reasons to keep on course with government operating on a business basis were manifold. Not the least of which was the reality, Coolidge observed, that this “is the first mid-year meeting that has been held when the estimated income and expenditures did not show the expectation of a large deficit.” Not even Harding could lay claim to that astounding achievement. It was one thing to approach the end of the fiscal year, which would expire on June 30th, with enough political momentum to narrowly prevent the budget from dipping into a deficit. It was much more difficult to already experience a sizable surplus at the middle of the year and watch it increase, not diminish, by June.

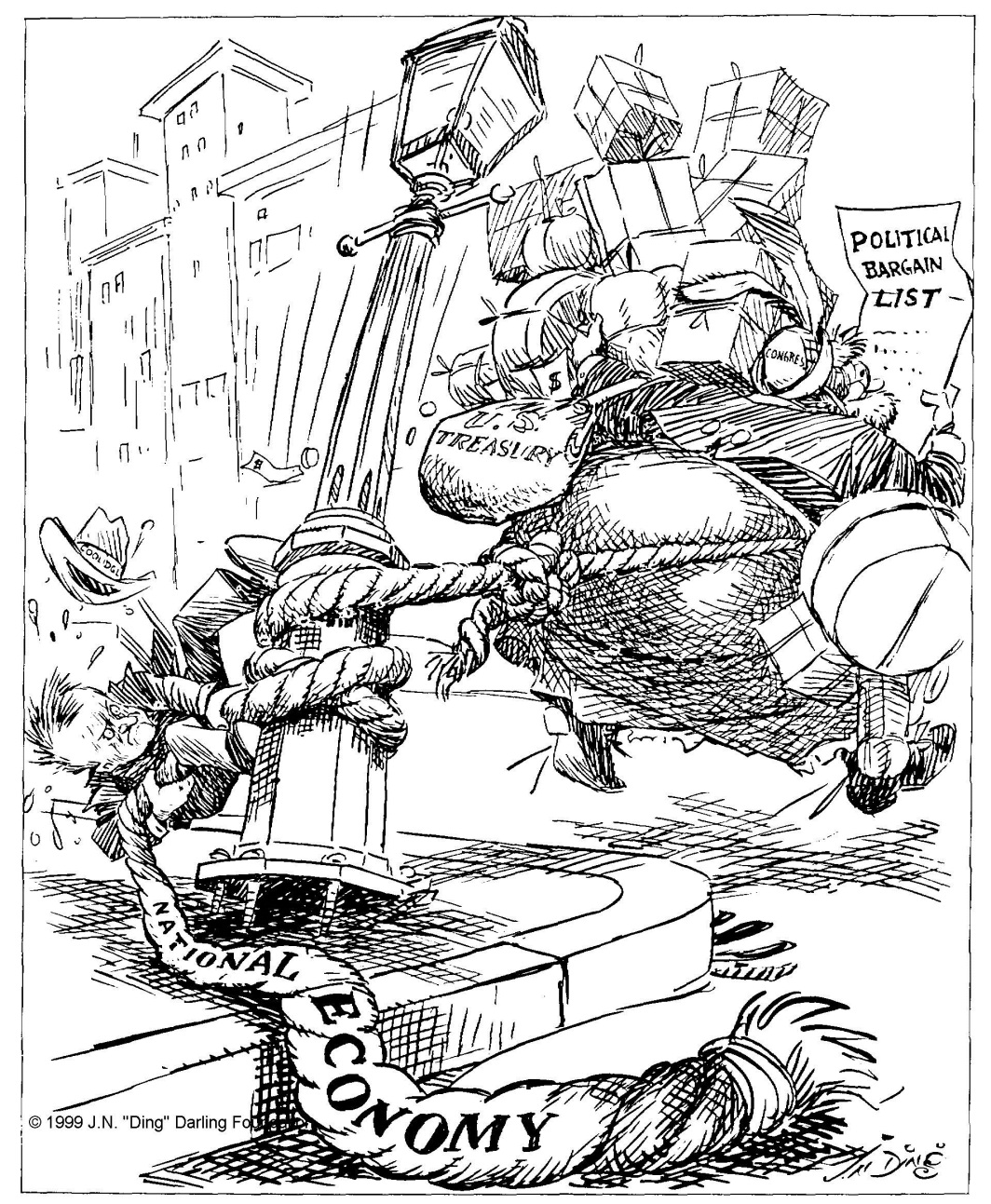

“And the first thing he tackled was the lock on the chicken coop” by “Ding” Darling, Des Moines Register, December 11, 1923.

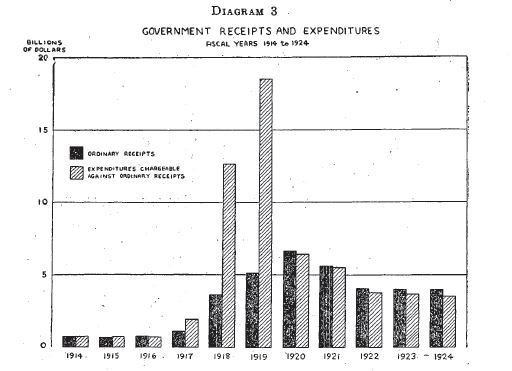

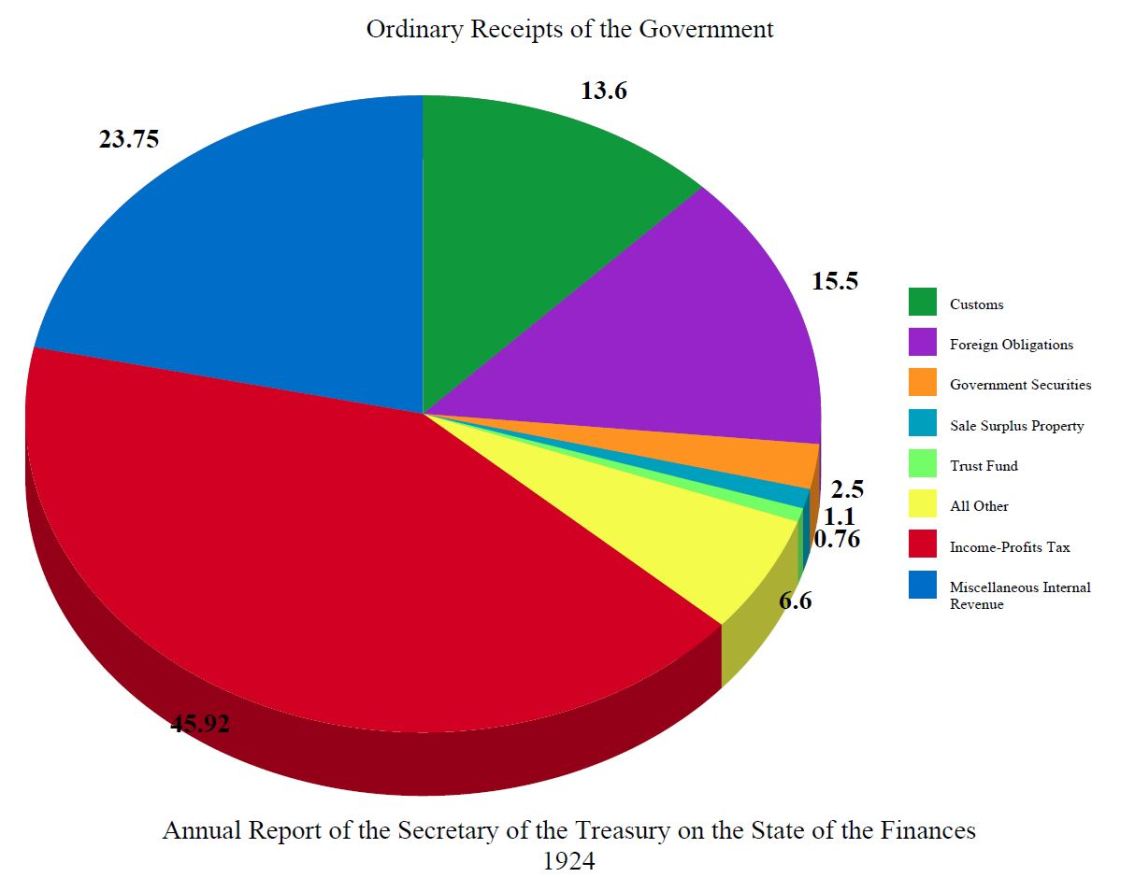

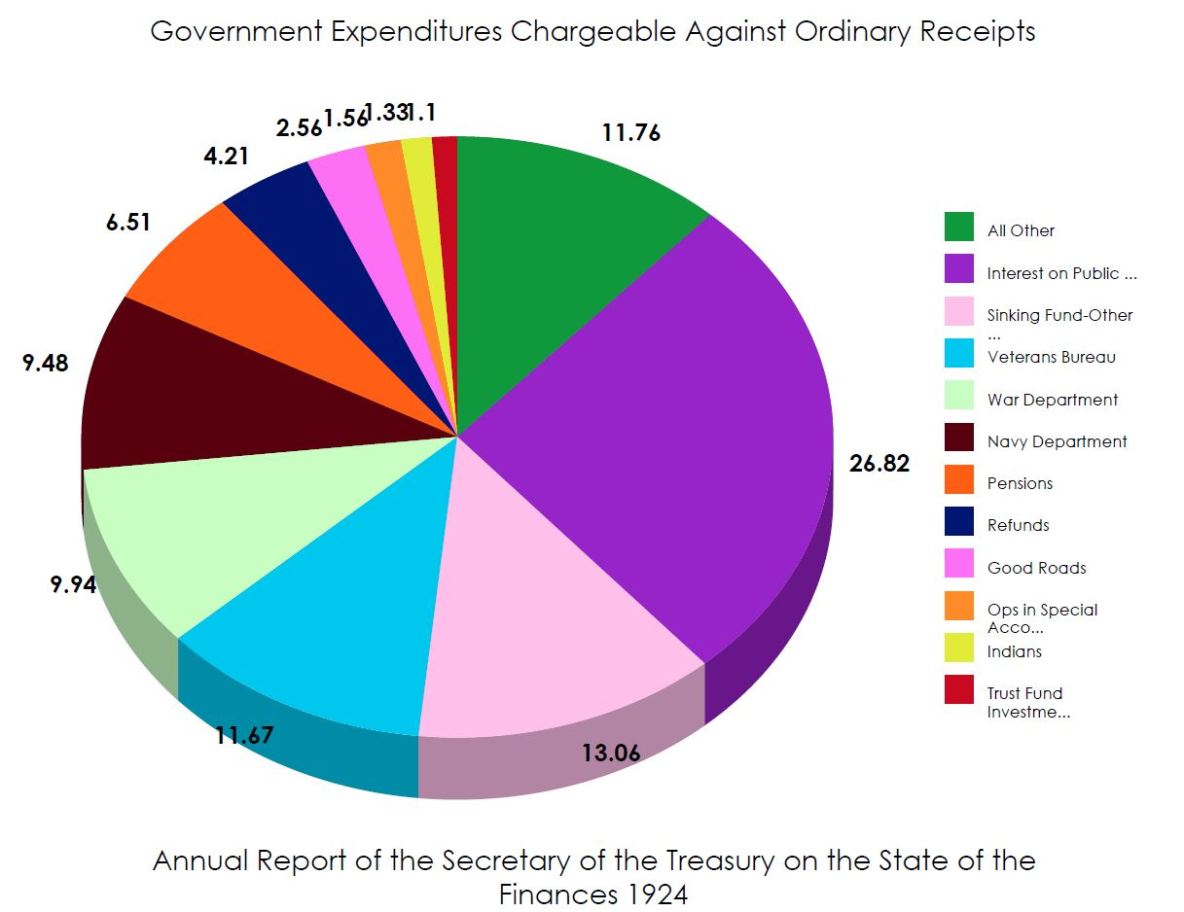

By the seventh meeting of the Business Organization, President Coolidge would announce that his estimate in January had grown another $10 million finally totaling $309,657,460 for 1923. The surplus of 1924, however, would be even greater, as Mellon, the Treasury Secretary, would report it to be the largest in our government’s history at $505,366,986. By every measure, keeping government working like a business was proving successful. The ordinary expenses percentage of the budget were to be kept down to $1.7 million, a goal reached to Coolidge’s satisfaction before the mid-year meeting in January. Neither had the sharp increase in the surplus been a fluke. The figures from the last three years, Coolidge would recount in June, verified that a “progressive and consistent reduction in expenditures,” thanks to the Budget Act, had hammered away at the growth of spending, actually cutting its advance. The decreases did not fluctuate, occurring merely one year or two, but steadily went down each year: $3,795,000,000 in 1922; $3,697,000,000 in 1923; and $3,497,000,000 in 1924. This was all the more impressive considering receipts were going down as well: $4,109,000,000 in 1922; $4,007,000 in 1923; and $3,995,000,000 in 1924.

Government Receipts and Expenditures, 1914-1924. Source: Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury 1924.

How could the government be taking in less overall but still be turning in larger and larger surpluses? As Coolidge had repudiated “Bargain Counter Government” in state politics, he refused to be misunderstood now. “I am not advocating parsimony, I want to be liberal. Public service is entitled to a suitable reward. But there is a distinct limit to the amount of public service we can profitably employ. We require national defense, but it must be limited. We need public improvements, but they must be gradual. We have to make some capital investments, but they must be certain to give fair returns. Every dollar expended must be made in the light of all our national resources, and all our national needs. It is here that the Budget system gets its strength as a method of fiscal administration.”

Of his Budget Director, President Coolidge said at the seventh Business Organization meeting, June 30, 1924: “He is human. He hates to say no. But he is a brave man, and he does his duty without fear or favor. This Nation is his debtor.”

Spending today would only preclude the ability to spend more tomorrow. Coolidge and his team knew also that taxation “should not be used as a field for socialistic experiment, or as a club to punish success, but as a means of raising revenue to support the Government.” This would not be done by taxing the producers out of existence, killing the means of next year’s revenue. Coolidge, Lord and Mellon understood that the need for revenue, while important, would take care of itself once you removed the obstacles to freedom, protecting, not penalizing, “the right of the people to their own property” and the rewards of one’s own industry. Revenue was not the problem, “excessive taxes” were.

While tax reform was ultimately the objective, tax reduction had to be enacted first to make future improvements possible. “There is scarcely an economic ill anywhere in our country that cannot be traced directly or indirectly to high taxes. To increase that burden is to disregard the general welfare. Through constructive economy, to decrease taxes is to enlarge the reward of every one who toils.” Selecting who benefits and who suffers via taxation is a dereliction of our duty to all the people, the President warned. This was the single purpose of their bi-annual meetings. It was not to hear each other talk, to have their words enter the record full long on good intentions but short on action, it was to ensure maximum benefits “accrue to the whole people” from tax reduction. In all their efforts, all their sacrifices and savings, “you must bear in mind,” Coolidge admonished, “that you are making them for the people of our country. There could be no nobler cause or one showing higher patriotism. Bear in mind always that we are here as the servants of the people and that only as we serve them well and faithfully shall we succeed.”

Consequently, revenue rose while income tax rates fell again, with the new tax bill of 1924, a 27% drop from what had been a top marginal rate of 73% three years before under the Wilson administration. Many taxes had been slashed or eliminated altogether. The resulting economic recovery was not supposed to happen. Revenue should have continued to fall short when taxes were cut, so said conventional wisdom. It was through spending that we avoid deficits and depression, it was claimed. Yet, the “score” Coolidge was reading furnished hard proof of how false this mentality was. “The budget has been a success,” the President retorted. “You have demonstrated that there can be, and is, a business organization of the Government. With the easing of conditions, the time is at hand when we shall decide whether a business administration is to continue, or whether our Government is to lapse into the old unbusinesslike and wasteful extravagance.” The enemies of this “intensive campaign in behalf of the people” for economy were “extravagance and inefficiency,” after all, not tax reduction or business budgeting.

Courtesy of Frasier, http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/.

This is why these January and June meetings of Business Organization were so crucial. Once each department had submitted their requested appropriations to the President, that was all they would get that year. “Supplemental estimates” extracting additional funds later in the course of the year would find no sympathies from Coolidge. Genuine emergencies may warrant amounts unforeseeable beforehand, but Calvin would not countenance a regular deviation from the reality of living within one’s means. If you failed to plan ahead sufficiently, you would have to learn to do without. After all, since the Congress, as representatives of the people, had appropriated specific funds by law “we must confine our operation within the limit of these funds. We have neither the authority nor the right to incur obligations beyond these funds.”

The budget was not to become a political instrument meting out penalties against enemies and bestowing rewards to friends, it was to remain “impersonal, impartial and non-political” despite the intense pressures to show preferences. “I urge upon all of you,” Coolidge declared, “to view your requirements in the sole light of their necessity from a standpoint of the interests of the whole Government.” Such was the way the rest of the country lived. Why should there be a different set of rules for Washington?

Courtesy of Frasier, http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/.

President Coolidge saw the dangers of an open-ended and limitless rationalization for Federal subsidies to the States. Even then “ample precedent” existed for “unlimited expansion” of this troubling expansion of government activities into broader and broader spheres. It ran against a sound business basis to take from the states what properly fell within their duties. Neither was it right to take from Massachusetts to pay for Minnesota. Each state held a responsibility for its own direction. “Efficiency of Federal operations is impaired as their scope is unduly enlarged. Efficiency of the State Governments is impaired as they relinquish and turn over to the Federal Government responsibilities which are rightfully theirs.”

The success of the last three years would only continue if everyone coordinated efforts without assuming the responsibilities of others. The Congress must not abandon economy, the executive departments and bureau chiefs could not venture out with contradictory aims. The people had to be heard. The law had to be honored. Each subordinate must look to the Chief Executive for approval of each department’s share of the President’s singular budget laid before the Congress each December. Everyone must share that common goal and be heading in the same direction. This also meant everyone needed to save out of what was appropriated, not spend it all so that next year more could be requested. Anything less would be a regression from the advances secured the last three years and a return to the inefficient, wasteful chaos of government as usual.

The work that had commenced so boldly three years before, to introduce business practices in the operation of government was anything but certain as a policy for the future. It was not a foregone conclusion that sound budgeting and strict adherence to constructive economy would last. Without patient and disciplined leadership, the incredible record of the Coolidge era may never have happened. Without Coolidge’s determination, debt would likely have never been paid down roughly $1 billion a year plus $120 million annually in interest payments. Without a President resolved to keep moving forward, there would have been no $175 million in excess of his original estimate. Had it not been for the unifying abilities of Coolidge and his team, $55 million would never have been cut away from the budget estimates of 1925, a total $232 million smaller than the appropriations of 1924.

These were not mere numbers on a spreadsheet to Coolidge, they were real lives impacted for the better. As he closed each meeting of the Business Organization in January and then in June, he reminded the hundreds present what their work meant. “[I]f we remember that every dollar of public money which we pay out has to be earned. It represents the toil of the people. It is so much taken away from everything they produce–so much added to everything they buy. There will be no doubt about the result if we insist that for each dollar spent there be a dollar of value received.”

“What every head of the household can appreciate” by “Ding” Darling, Des Moines Register, May 18, 1924.

Therefore, “[w]e must have no carelessness in our dealing with public property or the expenditure of public money. Such a condition is characteristic either of an undeveloped people, or of a decadent civilization. America is neither. It stands out strong and vigorous and mature. We must have an administration which is marked, not by the inexperience of youth, or the futility of age, but by the character and ability of maturity. We have had the self control to put into effect the Budget system, to live under it and in accordance with it. It is an accomplishment in the art of self government of the very highest importance. It means that the American Government is not a spendthrift, and that it is not lacking in the force or disposition to organize and administer its finances in a scientific way. To maintain this condition puts us constantly on trial. It requires us to demonstrate whether we are weaklings, or whether we have strength of character. It is not too much to say that it is a measure of the power and integrity of the civilization which we represent. I have a firm faith in your ability to maintain this position, and in the will of the American people to support you in that determination. In that faith in you and them, I propose to persevere. I am for economy. After that I am for more economy. At this time and under present conditions that is my conception of serving all the people.”

Seizing the opportunity to read the “score” of government’s activities to a nation-wide audience, Coolidge showed why Washington needs to continue being held to sound business standards and that when Americans join together to be heard, government is forced to listen. America is better for having been led by so tenacious and resolute a President as Calvin Coolidge.