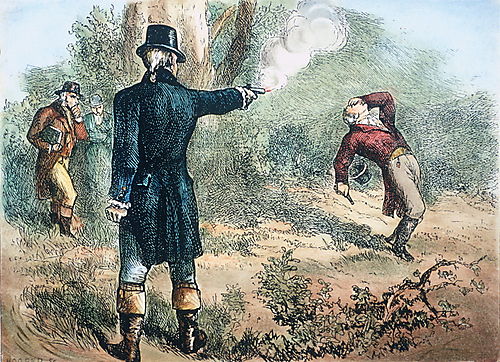

Two hundred and ten years ago today the death of Alexander Hamilton in a duel with Aaron Burr abruptly ended the life and public career of one of the most inflammatory and yet accomplished men of the Founding generation. Hamilton, one of Calvin Coolidge’s most respected figures, has appeared on America’s ten-dollar bill since July 10, 1929 in recognition of his preeminent role as the founder of our national system of finance. His legacy in cementing party politics is less known and even less appreciated. As history bears out, however, rough-and-tumble partisanship is anything but new to our time. Hamilton’s death demonstrates that, as polarizing as many today feel it is, what is happening now hardly compares to the days of Hamilton. Consider the imprisonment of opposition newspaper editors under the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 and the resulting Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions arguing for state invalidation of Congressional acts. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, impeached and nearly removed from office for his unconcealed advocacy of Federalist causes, tested the very limits of partisanship and national integrity later in the same year Hamilton died. Consider the violent rhetoric of the 1800 election from James T. Callender’s scandalmongering pen and Philip Freneau’s National Gazette to Hamilton’s spirited campaign not only against Jefferson’s “womanish attachment to France and a womanish resentment of Great Britain” but also the venom of The Porcupine’s Gazette against the Republican opposition. Jefferson’s “ho-mance,” as it might be termed today, with Revolutionary France would continue to express itself in unrestrained enthusiasm while Federalists were labeled as the actual “Reign of Terror.” Yet, as we know, America survived it all.

Two hundred and ten years ago today the death of Alexander Hamilton in a duel with Aaron Burr abruptly ended the life and public career of one of the most inflammatory and yet accomplished men of the Founding generation. Hamilton, one of Calvin Coolidge’s most respected figures, has appeared on America’s ten-dollar bill since July 10, 1929 in recognition of his preeminent role as the founder of our national system of finance. His legacy in cementing party politics is less known and even less appreciated. As history bears out, however, rough-and-tumble partisanship is anything but new to our time. Hamilton’s death demonstrates that, as polarizing as many today feel it is, what is happening now hardly compares to the days of Hamilton. Consider the imprisonment of opposition newspaper editors under the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 and the resulting Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions arguing for state invalidation of Congressional acts. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, impeached and nearly removed from office for his unconcealed advocacy of Federalist causes, tested the very limits of partisanship and national integrity later in the same year Hamilton died. Consider the violent rhetoric of the 1800 election from James T. Callender’s scandalmongering pen and Philip Freneau’s National Gazette to Hamilton’s spirited campaign not only against Jefferson’s “womanish attachment to France and a womanish resentment of Great Britain” but also the venom of The Porcupine’s Gazette against the Republican opposition. Jefferson’s “ho-mance,” as it might be termed today, with Revolutionary France would continue to express itself in unrestrained enthusiasm while Federalists were labeled as the actual “Reign of Terror.” Yet, as we know, America survived it all.

Partisanship and what many would consider incivility today have been with us since the founding. Consider the furious threats of the New England states to secede from the Union should Madison continue “his war” against Britain after 1812. Consider the road leading to 1861, from the Nullification Crisis of the Jackson administration to the bloodshed subsequent to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Consider, for instance, 1856 when Representative Preston Brooks, in defense of impugned honor, took a cane to Senator Charles Sumner’s head, beating him into unconsciousness on the Senate floor. Consider the imposition of strict, even malicious, means during Reconstruction in the 1860s and 70s, exacting vengeance, not justice, from the seceded states of the South. Consider the partisan upheaval of the 1890s, which pitted Democrats and Republicans in fierce lines of division over immigration, the gold standard and other public policy questions.

The 1920s were no exception to this rule. In Coolidge’s own time, elected officials mockingly read into the Congressional record absurd poems ridiculing the President’s use of a mechanical horse gifted to him. Missouri Democrat, James A. Reed, would make an industry of hurling insults and incendiary rhetoric during Cal’s administration just as California Republican Hiram Johnson would. James Cox, the Democrat candidate for President in 1920, lamented, “There is behind Senator Harding the Afro-American party…to stir up troubles among the Colored people upon the false claims that it can bring social equality, thereby subjecting the unsuspecting Colored people to the counterattacks of those fomenting racial prejudice.” The rhetoric of race-baiting and bigotry existed even in what too many mistakenly assume was some kind of “golden age of civility,” when parties worked together without name-calling or substantial disagreements on policy. Of course, we recall Dorothy Parker’s sarcastic response upon learning of Coolidge’s death in 1933, asking, “How could they tell?” The point, as Pietro S. Nivola of the Brookings Institution, reminds us, is that the “severity of today’s partisan discord pales in comparison with these epic clashes from the republic’s early years.” Truthful rhetoric had little restraint on this or any other heady era of partisan back-and-forth. Yet, the country survived each time.

Nivola further shows how partisanship, far from a cause for dismay to the Founders, serves a very beneficial purpose: It gives the electorate a choice. Voter participation rises when clear contrasts on principle are exemplified. As Nivola observes, greater turnout is hardly the sign of an unhealthy polity. Besides, bipartisanship has proven to be no sure safeguard at all for sound legislation, whether it be the Social Security Act of 1935, “hefty agriculture subsidies,” the “sacred cows” of energy lobbies or the Medicare law of 2003. In each case, the “benefits to taxpayers” remain dubious at best. Nivola recounts the findings of McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal, who conclude that polarization is on the upswing but Nivola places this in historical perspective. It is no unprecedented or novel partisanship we are witnessing today.

Enter Calvin Coolidge. The defense of our dual-party framework is one of his most emphatic imprints on the development of political thought. To Cal, partisanship was not inherently harmful to the country. After all, he did say, “While an independent attitude on the part of the citizen is not without a certain public advantage, yet it is necessary under our form of government to have political parties. Unless some one is a partisan, no one can be an independent.” The voters of this country choose between two distinct sets of party principles. The platforms of each party must not simply mirror each other. The electorate is not served by attempting to “one-up” the other side. It must campaign on and then follow-through with its platform.

To Coolidge, principles must translate into effectual governance. “Unless those who are elected on the same party platform associate themselves together to carry out its provisions, the election becomes a mockery.” Channeling both Madison and Hamilton, Coolidge knew that party government is the expression of the electorate’s will. Supplanting actual revolution, a process of orderly and lawful change takes place through elections every two years. “But,” as President Coolidge declared during his Inaugural Address, “if there is to be responsible party government, the party label must be something more than a mere device for securing office.” It must continue as a vital force in governing. That means partisanship.

Coolidge had seen what a “narrow and bigoted” perversion of partisanship had inflicted on the nation under the Wilson administration. His vice-presidential opponent in 1920, Franklin D. Roosevelt, had perfected it into an art form, criticizing Coolidge for his remarks about the “miasma” of Wilson’s militant and “unconstitutional” regime. As Cal surveyed the years of Democrat Party control, he spoke in Boston on September 18, 1920, saying, “The American people are turning from the contemplation of a mirage which, for a time, they mistook for a reality. When the political history of the past eight years is written it will resemble nothing so much as a chapter of accidents…The abounding prosperity of the Nation was turned to a state of adversity by breaking down the system of protection and by destroying the confidence of those engaged in all business enterprise. The cost of living was not lowered, but profitable employment, the only means wherewith the people could meet any cost, reached well nigh the point of disappearance. The charge laid against Republicans of countenancing the wicked principle of putting the dollar above the man, was entirely outdone by the Democratic practice, which put the dollar completely out of reach of the man…The very spirit of America withered, and the glory of the nation for the time departed…”

Then Coolidge, surveying the slate of Republican candidates in nationally and in Massachusetts, proclaimed his commitment: “In support of these candidates and the principles they represent, the country is turning again to realities. It wants to turn away from the mirage of false hopes and false security. It wants to be done with miasma of war. It wants the security of peace. It wants to live again under the government of the Constitution” (emphasis added). Even then, Coolidge knew that being partisan was not the culprit, a “narrow” and “bigoted” opposition for its own sake, was. There remained a valid place for partisan principles working with the Golden Rule instead of selfish and petty criticism as the expedient means to its own ends. As Coolidge showed, partisanship is not inherently incompatible with civility.

Calls for civility have all too often become thinly disguised efforts to muzzle any manifestation of disagreement, however tepid, guilting opposition into self-imposed compliance. No longer implementing what Madison called “the republican principle” of majority party coherence, the agenda of powerful minorities have created the impression that Washington’s “gridlock” problem is directly attributable to rogue obstructionists. The problem, it is claimed, comes not from a Republican House majority actively partnering with the Democrat Senate majority but from conservative or “Tea Party” partisans like Sarah Palin, Ted Cruz, Mike Lee and Rand Paul who point out this discrepancy of party commitments. Instead of the “reasonable” and “bipartisan” “adults” like Susan Collins, John McCain, Lindsey Graham and John Boehner, these “public enemies,” like Ted Cruz, are ostracized for nothing more than articulating ideals grounded in the conviction that their Party is a choice, not an echo, as Senator Goldwater once said. In truth, the opposition of those who know they are Taxed Enough Already has become the only group brave enough to hold a Republican Party, so cowed by decades of false accusations, to its elected mission. By demonizing anyone who defends a government of limited powers operating by our consent, any challenge by principled partisanship is marginalized as “extreme” and worse. Responsible governing takes a back seat to the game of appearing cooperative, sacrificing very valid reasons for party opposition on principle in place of the illusion of “bipartisanship.” Which, in reality, is nothing more than a disregard for party loyalty in order to form an altogether unelected entity one might call, a “Party of Power,” implementing a patchwork of minority agendas that the country does not want, did not choose and runs contrary to its interests as a whole.

No longer tempering legislation by debate or careful circumspection, measures, however destructive they be in fact, are hastily and emotionally implemented into law. Efforts to, at minimum, slow down this headlong rush into disaster are met with vitriol not only from outside one’s party but within it. What we see now at work is democratic mob rule not our long-cherished dual party system. If party government is to remain an “effective instrument,” as Coolidge called it, it must retain the confidence and consent of the governed. The party sent to control the part of the government to which it has been elected, must control it, enacting a consistent and united direction that upholds the party principles. “Any other course is bad faith,” Coolidge affirmed, “and a violation of the party pledges.” Being a maverick as the situation suits is not something noble and heroic, in other words. It is bad faith, a betrayal of what one is and commits to do. It is in party loyalty — which is simply a fidelity to the principles for which the party stands — that preserves faith in the people and their institutions by acting on what they have chosen be done.

Leaders can mislead but parties are entrusted with responsibility to carry out their ideals. Sometimes, as Coolidge said, keeping those promises means collaborating with those outside the party to keep one’s party honest. He did so without descending into mean vindictiveness, but he still championed those policies and positions that his Party committed itself to perform. As Coolidge wrote in his memoirs, “The independent voter who has joined with others in placing a party nominee in office finds his efforts were all in vain, if the person he helps elect refuses or neglects to keep the platform pledges of his party.”

When others wavered and deviated, Coolidge held course. He owed as much to the American electorate. Not all had voted for him, of course, but a majority party had been sent to assume command of the Executive and Legislative branches and, as far as it depended upon him, they would adhere to a platform that was partisan, a vision that meant something, policy proposals that coherently and clearly differentiated from what the Democrats would do. Coolidge would not govern by a different standard than what elected him. The anniversary of Hamilton’s untimely death should remind us that partisanship is not novel to our time. Just as civility did not sweep the country under Coolidge, so principled partisanship is not incompatible or somehow destructive to the country now. If it were, America would have died in its infancy. Coolidge articulates the abiding importance our two party system plays for government to remain an effective expression of our will. It means some opposition will unavoidably come our way. It means not everyone will agree to temper opposition along principled lines and thus rush into the bigoted and obsessive excesses possible with even good things. This does not mean party opposition is neither sound nor beneficial. Coolidge demonstrates that a principled partisanship has and will continue to serve this country well.