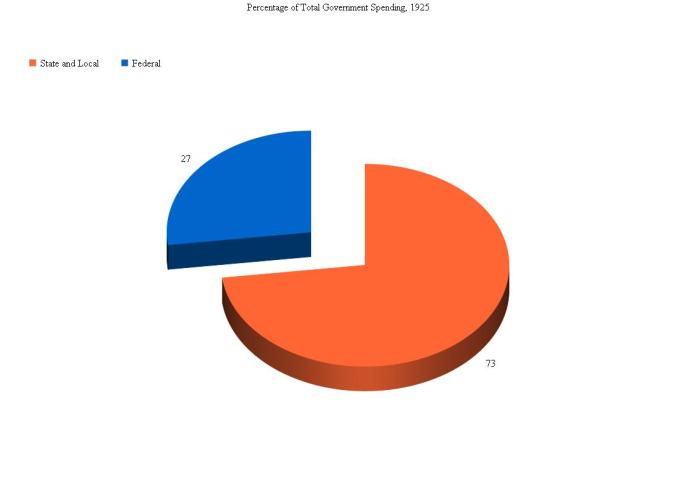

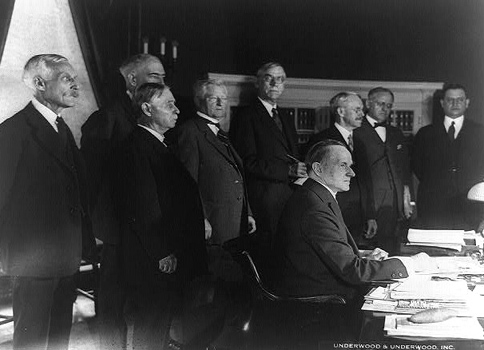

President Coolidge signs the Revenue Act of 1926, February 26, 1926. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

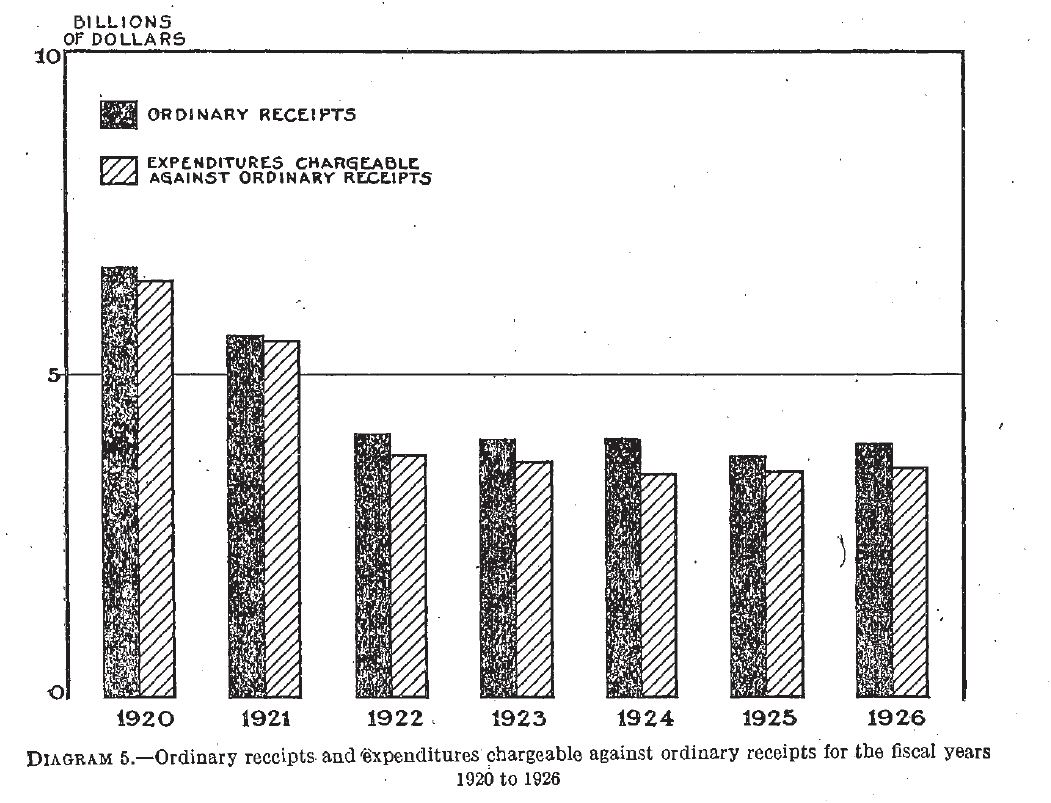

Instituted to measure the success or shortfall of the Budget system year by year, the Business Organization of the Government met twice annually, once in January and at the end of the fiscal year each June. Led by the President and his Budget Bureau Director, it would be left to Coolidge and Director Lord to lift these meetings out of the realm of a burdensome and tedious anomaly from the status quo. Instead of “business as usual” the Coolidge administration walked what it talked, bringing a focused and even entertainingly competitive application of private sector principles to what had been a wasteful and inefficient government norm. As everyone knew, however, when the department heads, bureau chiefs and agency leads met with the President and the Budget Bureau Director for the tenth time on January 30, 1926, the progress of four and a half years could come stall, abruptly halt or unravel before their eyes if any one of them succumbed to the pressures continually upon them to revert to the old habits of Washington as usual. Now elected in his own right, there was no code of honor binding Coolidge to adhere to Harding’s budget program. He continued it because it was morally right and necessary for the country, whoever occupied the White House. Each month was making it more and more difficult, however, for those who made his budgets reality every year. Prosperity was abounding. The economy was roaring and revenue had only increased with the expectations of a new tax bill, which would be passed less than a month after their meeting on February 26th, drastically improving conditions from what had already been beneficial relief under the Revenue Act two years before.

A student of government and especially of tax policy, President Coolidge, began to see a pattern of both good prospects and detrimental concerns for the future. The meeting later that year, on June 21, would make it even clearer: government expenses were reaching a natural plateau, that made future possibilities for drastic cutting genuinely no longer possible. By that summer, Coolidge reminded his audience again that the past five years under a Budget system had removed $2 billion of waste from the Federal budget not once or twice, but five times. However, the Federal Budget, chopped from $5.5 billion in 1921, now stood at some $3 billion but was very close to reaching an impasse. Progress would begin undoing itself to the harm of every American household. The standards of living would begin to fall under disrepair and the cost of government would have to return to extracting the earnings of the people who would again work less for themselves and more for government. To Coolidge this was an intolerable regression. Coolidge made emphatically clear that this program was not about saving a dollar if it meant destroying an individual. Each partner in this great enterprise was saving to serve people, not money. Closing schools, abolishing courts, disbanding the police forces and discontinuing fire departments was not moving in the direction of civilization but back toward anarchy and the law of might triumphs over all.

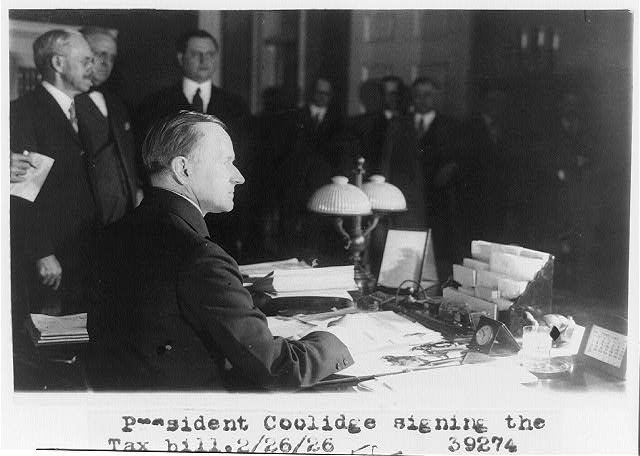

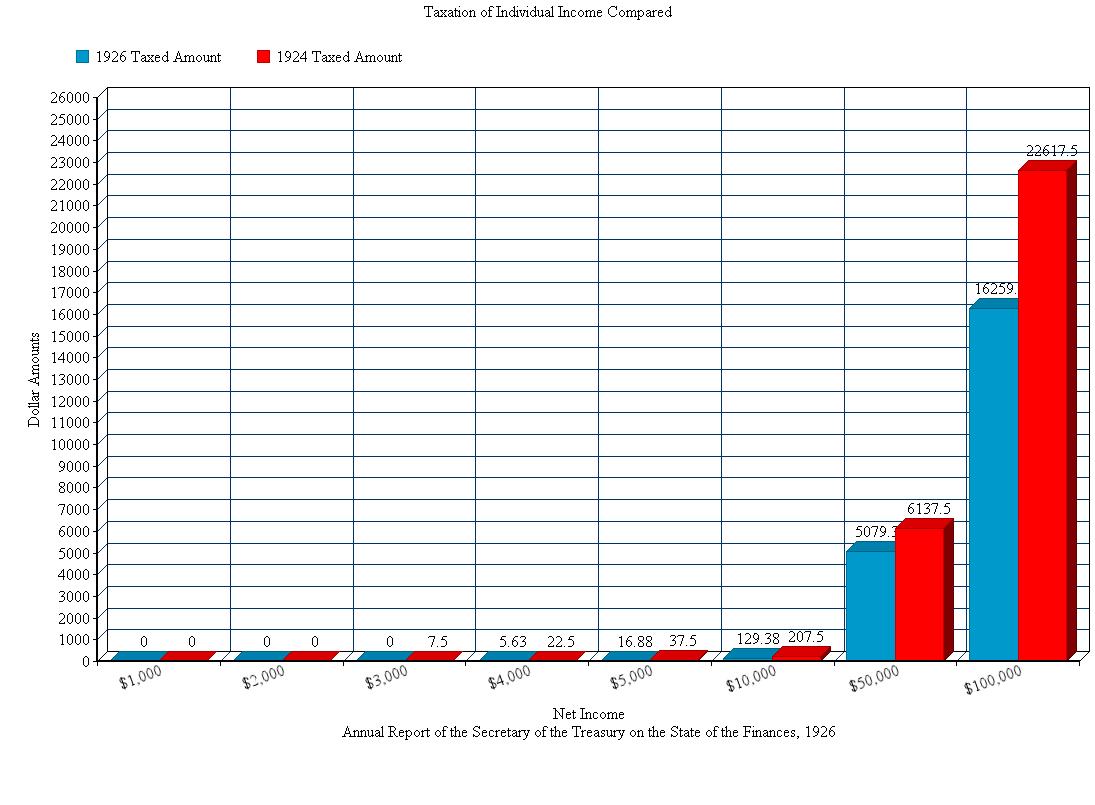

Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances, 1926. Courtesy of Fraser, http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/.

Courtesy of Fraser, http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/.

This did not mean that the Budget system had completed its work or that constructive economy was done. Far from it. Now came the most difficult juncture: Would constructive economy, what Coolidge termed the securing of more results for less cost — the people getting the most possible out of every tax dollar, continue? After all, he approached the question not with a concern for where government was going to find reliable streams of revenue but how every cent of revenue could be saved and only expended to maximum benefit of those who worked to earn it, American taxpayers. As Coolidge declared in the June meeting of 1926, “The real purpose for which we are assembled is to discuss plans and adopt policies which will affect in their actual daily life the welfare, progress, and prosperity of 117,000,000 people. What we do here reaches into every home in the land. It determines whether the taxgatherer is going to require more money from the head of the household to meet the cost of maintaining the Government, or whether the taxgatherer is going to leave more money with the head of the household to meet the cost of maintaining the family. Our efforts here are translated into benefits for the head of the household and his family.”

These bi-annual meetings were anything but irrelevant abstractions, they directly impacted the lives of every person in the country. There were faces tied to every decision made in Washington. A choice to stop now and abandon constructive economy — however insignificant it seemed to each little office in government meant priceless blessings to the future good of families all across the country. Coolidge wanted to remind those who had partnered with his effort to budget that millions of real people waited at the end of their determination to uphold their obligation.

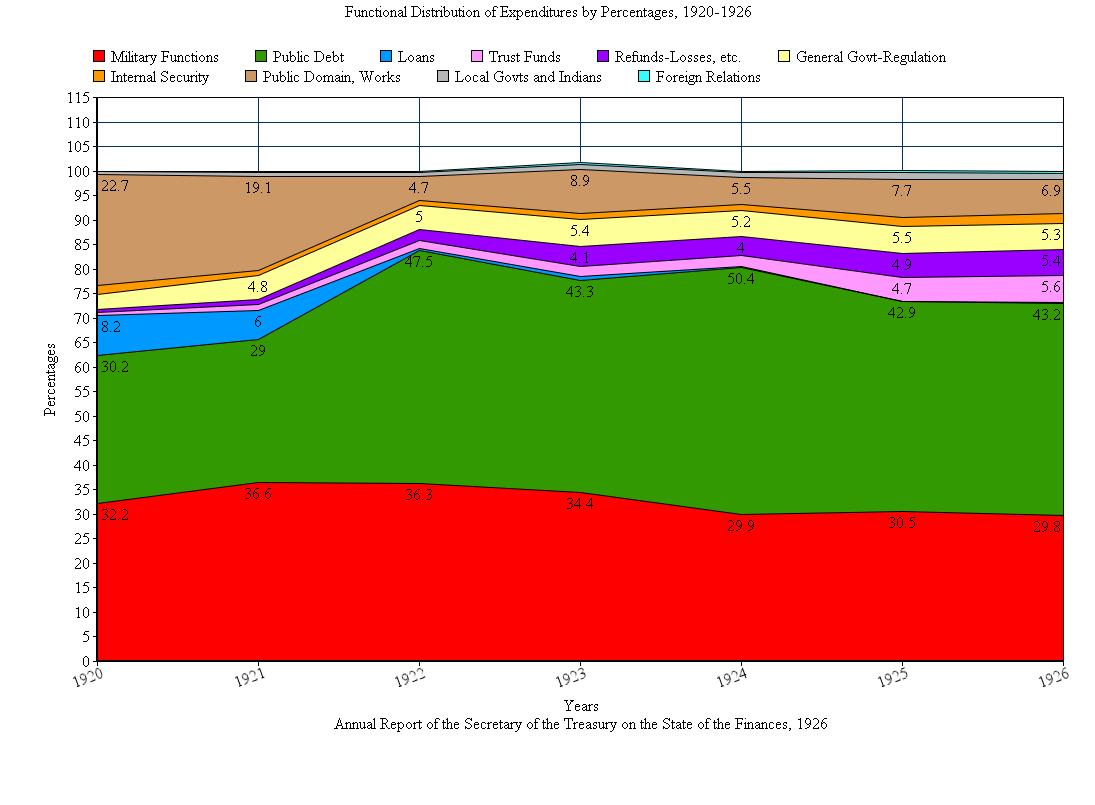

Functional Distribution of Expenditures FY 1920-1926. Courtesy of Fraser, http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/.

It was just as important to recognize that constructive economy was not simply an incessant negative, it sometimes called for reallocations of spending on new endeavors in order to secure even greater efficiency with the people’s money. The construction of public buildings, vacating the expensive rental of private property, would ensure that more was gained for less as property taxes would decrease and rental costs could be eliminated. Personnel, what everyone knew to be the biggest expenditure in the budget, had seen 5,000 names (roughly 1% of the total Federal workforce) at a cost of $8 million reduced from the payroll. These numbers were people to Coolidge who, he knew, would find the real value of their labor in the burgeoning marketplace without weighing down the American people at exaggerated prices from the public Treasury. Of course, when possible, efficiency meant moving one person unneeded in one department to where they were in need. Or, as Coolidge said in June, “I am encouraged in the thought that we can have further reduction of personnel without discharging a single person by the simple device of not filling all the vacancies that occur.”

The call of constructive economy summoned everyone to serve the taxpayer, from the newest clerk to the most senior administrator. Government work was not “good enough” to do less than any private business must do to meet the constant challenge of efficiency and solvency. This included travel costs and per diem rates. Government employees were not free to spend because it was there. The surplus of 1926 was no excuse to waste the money of the American people. “We are not striving to save the dollar simply to save it,” Coolidge declared. “We are not striving to save the dollar at the expense of the public service. Rather do we approach it from the other side and save the dollar for the good that it will bring to the people whom we serve. We can make the dollar purchase more by purchasing more wisely. We can eventually save money by a justified expenditure to-day which will reduce future annual unproductive expenditures. This is constructive economy.”

Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances, 1926. This chart especially illustrates the progressive rate of taxation in the Twenties, giving the lie to those who still claim taxation spared “the rich” while punishing “the common man.” The exact opposite was the case under Coolidge-Mellon tax policy.

The Revenue Act that would be passed in February 1926 finally achieved a number of the objections Coolidge had wanted done in 1924. Top marginal income rates were sliced to 25%, a 21% decrease from 1924. The new Act “relieved some 2,000,000 people from paying any direct tax and reduced the burden of all other taxpayers. General prosperity is the aggregate of the individual prosperity of our citizens. To permit the people to retain more of their own earnings is to increase their savings and purchasing capacity, which assures prosperity.” In 1926, married couples with no dependents, making the typical middle class bracket of $3,000 net, paid nothing. Single persons making $3,000 paid only $16.88. The laundry list of taxes invented during the war had governed some 50 categories of goods, now there were only 5. This meant a loss of $275 million in revenue and under the law “no compensating increases” were levied to replace them. Under the previous tax law, upwards of 40% of America’s businesses “with not one dollar of profit were obliged to pay a large tax.” In 1926, this ended so that businesses could make payroll, cover costs and barely break even without having to face a tax penalty for profits they did not make. Another provision withdrew individual income tax records from public disclosure requirements thereby helping to protect taxpayers from being targeted by those who deemed income or what someone else paid to be “unfair.” The rewards of this Act would continue to come to light in the coming year but it already confirmed the “theory that reduction of tax rates economically applied will stimulate business, and thereby increase taxable revenue.” Holding to the Budget system would ensure that the people obtained a maximum return on their investment.

“Who said they didn’t believe in Santa Claus?” by “Ding” Darling, The Des Moines Register, November 8, 1926.

Another cause of concern for Coolidge came from the budget estimates of the next two years, which held razor thin surpluses that could very easily evaporate should even the slightest unforeseen expense arise. It was evident that while revenue was increasing, several factors were going to begin undermining the success of future tax cuts if relied upon recklessly. First, President Coolidge was concerned that a reliance on the current sources of revenue to increase steadily was a misleading and faulty hope. The back taxes that had accrued so much of the increase in 1925 and 1926 were going away. There would not be another year of so ample a contribution to the surplus. The departments could not depend on this revenue in their appropriation requests to the President like they had in previous years. Constructive economy meant “preparation for the future.” If costs were wisely planned out, retrenchment would continue as it had the previous year, saving $24 million in reserve when all was said and done. This conscientious discipline of spending less than one had would only reap greater dividends for the future.

Second, President Coolidge was concerned that loose spending would foreclose any possibility of further tax reduction in the coming years. Tax rates had been cut three times by the summer of 1926, and the latest Revenue Act had secured much for the country that would only increase as the new year dawned. Yet, the President knew that government was even then taking too much from people’s earnings so that Americans were all the poorer for it. If those gathered to effect constructive economy deviated from that mission, surplus would soon melt into deficit, the budget would be overwhelmed with demands from every side and prosperity would be inundated with financial distress resulting in “want, misery, disorder, and the dissolution of society.” As he would repeat again in June, “The limit is close at hand when further expansion in the costs of government will bring the danger of stagnation and financial depression.” Little could anyone know how prescient this statement would be when, by 1930, market downturn would become depression through that very cause. Coolidge’s warnings were not political hyperbole either, the men and women gathered for the Business Organization of the Government had seen these dangers manifest firsthand from 1919 through the turmoil of 1921. While part of the increase in revenue from the Revenue Act of 1926 would come from business expecting reductions, it would not help anyone to infer more tax cuts were to be expected in the future. Doing so too soon would have the reverse effect of precluding cuts as government would become lackadaisical about responsible budgeting.

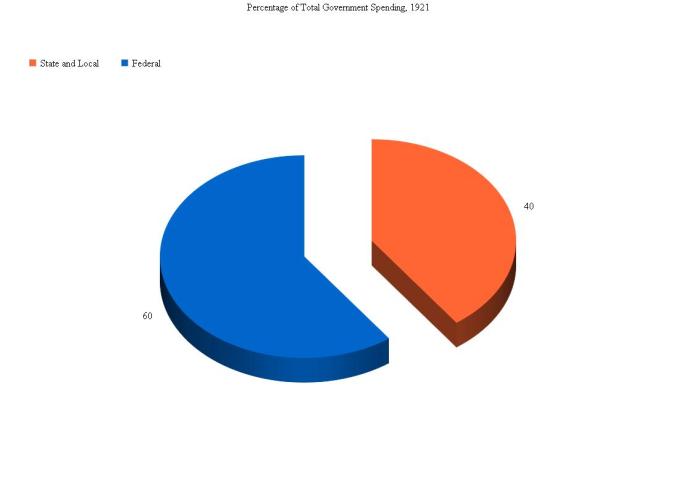

Third, President Coolidge was concerned with state and local spending trends. While the Federal Government had faithfully maintained the cutting of expenditures with an accompanying reduction in debts and taxes, States and municipalities around the country embraced a “mounting tide of expenditure and indebtedness.” During the same five years that the Federal Government had brought expenses down more than $2 billion, $4 billion in increases were being expended by State, county and municipal authorities. When the cost of all government nationwide approached $9.5 billion in 1921, 60% of that total was Federal. In 1925, when the cost of all government stood at $11.5 billion, only 27% of the total fell to the Federal level. Coolidge explained the basis for this dramatic turn-around. “The answer to this reduction of 33 per cent in the Federal share of all government costs is not that we are performing less service for the people or neglecting our physical plant. The real answer is that we have so far put our house in order as to decrease our demands upon the people and to give them more efficient government at less cost…There is cause for concern in this situation. It is fraught with grave consequences to the public welfare. The Federal Government has decreased its cost by practicing the homely virtue of thrift. This has not been an easy task. It has required cooperative effort and sacrifice in every direction. If the interests of the people demanded this action on the part of the Federal Government, surely they would seem to demand similar action with regard to the increase in these other local governmental costs. This suggestion is not meant as a criticism of the officers of our local governments. It is rather a statement of fact. It shows how hard it is in these times to reduce the costs, taxes, and debts of governments. But it can be done if the people will cooperate.”

The President signs the Revenue Act, 1926. Legislative leaders of both parties bask in the light of the Coolidge team, L to R: Democrat Furnifold M. Simmons of North Carolina (concealed by the flag hanging in the foreground); Democrat John N. Garner of Texas (directly behind Coolidge), who vehemently opposed tax cuts; President Coolidge (seated), flanked by Republicans Senator Reed Smoot of Utah, House Majority Leader John Q. Tilson of Connecticut and Representative William R. Green of Iowa; followed by Treasury Secretary Mellon, Budget Bureau Director Herbert M. Lord and the President’s secretary, Everett Sanders. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Legislators stand in the midst of the Coolidge tax policy team, with Democrat Senator Simmons standing in front of Mellon to flank the President’s chair with fellow Democrat from the House, “Texas Jack” Garner.

The people of the country had to remain behind these efforts of constructive economy just as much as the Congress, the President and his Executive Department. It was larger than any one person, one department or even one administration. Yet every individual, doing one’s part, was indispensable to the overall result. The President had relentlessly made the case for this effort every year for five years but without the experienced logic of Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon, the creative leadership of Budget Director Lord, the tenacious legislative skill of Appropriations Chairmen, Representative Martin B. Madden in the House and Senator Francis E. Warren in the Senate, the intense accounting discipline of Comptroller General John R. McCarl, or the rugged perseverance of thousands of Federal employees, who made all these ideals reality, the Budget System would have failed and the country probably would never have experienced the historic prosperity of the 1920s. It was a test throughout the country of the “success of self-government.” By using money, not as the end result, but as any other “utility — to advance the welfare of the human race” through “a wise expenditure, well balanced and within the means of the people,” America would pass that test worthy of freedom.

Senator Francis E. Warren of Wyoming, Chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, was instrumental with Representative Madden in the fight for tax reduction.

Comptroller General John R. McCarl served as head of the General Accounting Office for fifteen years, 1921-1936. As his term of office came to a close, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote of him, “Among the welter of Washington’s yes-men, he was a forthright, solitary and heartening no-man.” At the same time, the Hartford Courant observed, “McCarl was neither negligent, careless nor open to ‘suggestion.’ He made his rulings without fear or favor.” We can understand why Coolidge found him to be a steadfast ally and faithful public servant.

Representative Martin B. Madden (R-IL), who chaired the powerful House Appropriations Committee, is seen about to visit Coolidge at the White House, September 6, 1923.

“That is constructive economy,” Coolidge affirmed. “It does not partake of a mean and sordid nature; it is not narrow and selfish, but rather broad, generous, and ennobling, undertaking to deal justly with the whole situation by raising such revenues as the people can fairly bear to meet such expenditures are are fairly required…The result is America. Into the making of that result and its continued success your patriotic service and devotion is a contributing factor of enormous importance.” When all had been tallied, it meant something far more than “the saving of money.” It was a justification of our “wonderful American experiment for the advancement of human welfare.” After all, it “is not the only method by which we have built railroads, developed agriculture, created commerce, and established industry, not only the method by which we have made nearly 18 million automobiles and put a telephone and a radio into so large a proportion of our homes, but it is also the method by which we have founded schools, endowed hospitals, and erected places of religious worship. It is the material groundwork on which the whole fabric of society rests.” This meant so much more than material goods. “It has given to the average American a breadth of outlook, a variety of experience, and a richness of life that in former generations was entirely beyond the reach of even the most powerful princes.”

All the energy expended would be in vain were it not for “the keeping of our faith.” Our framework of popular government would implode at its very core if it throws “away self-restraint and self-control,” adopting economically unsound laws that squander this moral inheritance America is exemplifying to the world. “America has demonstrated that self-government can be administered as fairly to protect each individual in all his rights, whether they affect his person or his property. Under constitutional authority we tax everything, but we confiscate nothing. It is not through selfishness or wastefulness or arrogance, but through self-denial, conservation, and service that we shall build up the American spirit. This is the true constructive economy, the true faith on which our institutions rest.”