A view of the Willard Hotel during the 1920s. Note the flag out front identifies that the President is staying there.

“It had been our intention to take a house in Washington, but we found none to our liking. They were too small or too large. It was necessary for me to live within my income, which was little more than my salary and was charged with the cost of sending my boys to school. We therefore took two bedrooms with a dining room, and large reception room at the New Willard where we had every convenience” — Calvin Coolidge, writing of their arrival in Washington in the spring of 1921, The Autobiography, pp.157-8.

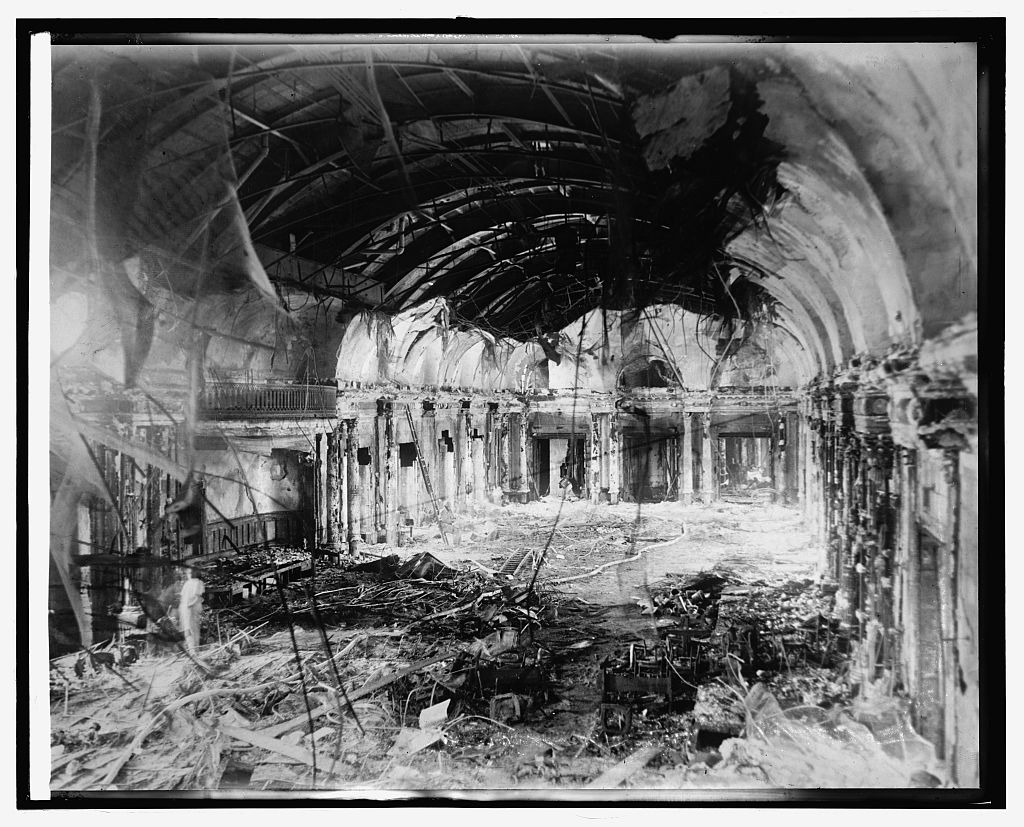

Known today as the Willard InterContinental, the hotel which the Coolidges called home from the spring of 1921 through much of August 1923, already enjoyed an illustrious reputation before their arrival. It would continue to function as a central location for several events throughout the Coolidge Era. It had been the host of every president since Franklin Pierce, who staged here before leaving for his inauguration in 1853. It was here that Pinkerton hid President-elect Lincoln, thwarting more than one assassination attempt in the weeks leading up to formal inauguration and subsequent history. Lincoln met leaders in the lobby and carried out business from his room, not unlike what the thirtieth President would do throughout August 1923. It was said that Grant, in his time, frequently sat down in the lobby to enjoy a cigar and drink. Established in 1816, the New Willard had many a story to be told. It would go on to make several occasions in history, such as the place where Martin Luther King composed his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial across from the Washington Monument. Yet, some of the hotel’s most dramatic moments happened during the stay of Calvin and Grace Coolidge. The best known of these is the fire that raged on the tenth floor, seven above the Coolidge’s rooms, on April 23, 1922. Incurring over $3.5 million in damage (by 2014 values), the danger was seen too late to avoid demolishing the ballroom on the top floor. Mistaken for the Vice President of the Hotel, Coolidge was first allowed to pass the fire marshal and begin to walk upstairs. Quickly confirming that Cal was the Vice President of the United States, he was kindly told to come back and wait from a safe distance, which he calmly did. The following day, he dispatched a gracious thank you to the officials who handled this unfortunate event so capably.

As the fire is put out, the Coolidges and some of their fellow guests watch from below. L to R: Miss J. Letley, A.H. Duerno, of Springfield Mass., O.H. Wigley of New York, Mrs. Coolidge and Vice President. Coolidge. Courtesy of Corbis Images.

Another instance, kept from public knowledge for many years, concerned the new President and a burglar, who had sneaked into their room during the night on August 23, 1923. What happened, told by Coolidge to a reporter named Frank MacCarthy who relayed it confidentially years later to Richard C. Garvey, the editor of The Daily News, out of Springfield, Massachusetts, was finally published fifty years later in 1983. MacCarthy would die soon after Mrs. Coolidge in 1957, but not before writing the incident down and passing it on to Mr. Garvey. Garvey brought the incident to light to mark the memory of Coolidge’s passing and remembrance week that year. The account goes like this: Coolidge awoke to see a figure in the room, having climbed through the window, searching through the President’s clothes. Finding his wallet, a watch and a charm, it seemed the thief would obtain what he was seeking with ease. “I wish you wouldn’t take that,” Cal said regarding the charm. Startled, the intruder was told to read the inscription on the piece, “Presented to Calvin Coolidge, Speaker of the House, by the Massachusetts General Court.” “Are you President Coolidge?” the young man asked with astonishment. “Yes…if you want money, let’s talk this over,” the President said coolly. Discovering that the youngster was there to get money for a train fare so that he and his schoolmate could get back to college, the President opened his wallet and gave him a $32 loan, exactly enough to cover the fare. As Garvey recounts, Coolidge called it a loan so that the young man would not have obtained the money by theft. The young man later paid back the amount in full.

The Coolidges, in their reception room at the Willard, August 4, 1923. Courtesy of the Everett Collection.

The Coolidges look through some of the many letters sent to them over the previous two days. Courtesy of Shorpy.

The final instance concerns another night visitor, this time a small bat which flew in through the open window one night, followed quickly by an owl. The bat was “herded” to the bathroom while the owl took up a perch on the mantel. There was no small excitement on the part of Mrs. Coolidge, whose stalwart hero, Cal, took care of their guests without much ado. It certainly brings an interesting element to the 1883 poem placed over their mantel back in Northampton, which read:

“A wise old owl lived in an oak

The more he saw the less he spoke

The less he spoke the more he heard.

Why can’t we all be like that wise old bird?”