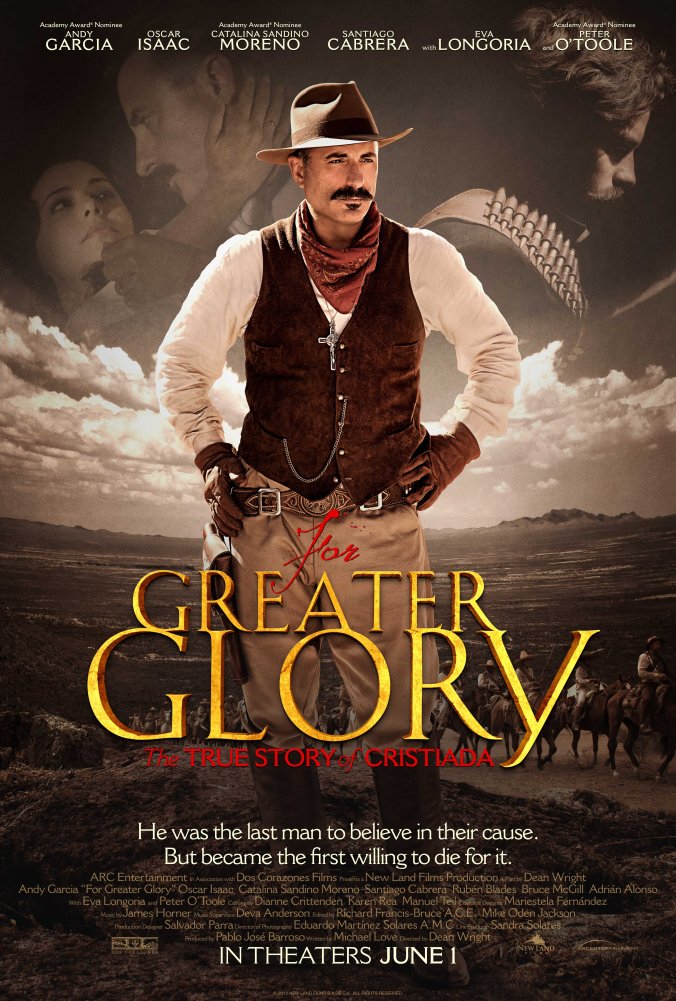

When the film For Greater Glory came out in 2012, it was met with the usual tepid reviews of skeptical critics. No less surprising was the outpour of enthusiastic praise from various conservative news sources for the historical drama. Some lauded it as a timely commentary on the fight for religious freedom against an intrusive government (read Hobby Lobby, Catholic contraception mandates and Obamacare). Others took the opportunity to grind an axe or two against the Catholic Church. This belated review will indulge in neither of these biased attempts at making the events relevant. Being an effort to relate a little known, and even less understood, conflict known as the Cristero War, the movie cannot possibly capture the full character of the people involved, events in sequence and the motives and decisions made over the course of three years with perfect inerrancy. No film can do that and not become an extended documentary. Still, it makes a number of avoidable mistakes that leave an impression not so much of what actually happened – the “true story of Cristiada” – but what many are comfortable believing about America’s role in that controversy. Aside from the horrendous casting and introduction of President Coolidge, along with placing a fine actor in a part that doesn’t fit the real Ambassador Dwight Morrow, the movie leaves the viewer with too simplistic and predictable a concept of how this terribly violent period of the Mexican Revolution resolved. It merely ties it neatly together in captions after the virtual martyrdom of General Gorostieta, played by Andy Garcia. The viewer is left to understand that while the churches reopened and the enforcement of government mandates on Catholics stopped, American involvement did nothing for the real martyrs and heroes, the Cristeros. The message between the lines is that America unwittingly helps the villain. It may have even made things worse for the script’s heroes, certain dialogue seems to say. In fact, Americans did what they always do, it is claimed by some: a deal with the devil in order to protect oil interests and our incessant policy of intervention. Morrow, played by Bruce Greenwood, is introduced as articulate and clearly able, but succumbs to the stereotypical persona of a well-meaning yet unprepared and ill-equipped American, blundering through his culture shock with conventional diplomacy to broker an agreement that works for the government but hurts the governed. Such a distortion is neither an honest rendition of what took place nor does it do justice to any of the original participants.

The demands of the Mexican Revolution, officially ended some six years before, continued to impact the country as the movie opens in 1926. A Constitution, duly ratified in 1917, included a number of Articles codifying nationalized ownership of land, curtailment of Catholic Church influence in government and other elements of a nationalist-socialist ideal to which Mexico was aspiring. Most of the provisions went unenforced for years and the Mexican government would be officially recognized contingent upon a legal respect for the property rights of foreigners agreed upon between then-President Obregon and the Coolidge administration in December 1923. The Mexican Supreme Court, two years before, had even ruled that property rights remained unimpaired by the 1917 Constitution. The relationship between Mexico and the United States began to decline again, however, with a new election inaugurating Plutarco Elias Calles in 1924, who before long made clear that he was not so inclined to honor the agreement made between America and his predecessor. As he launched a firm program to enforce the 1917 Constitution, an effort which began in earnest in 1926, his early successes in reform and administration were eclipsed by this leftward drift. Perceived as moving too slowly toward the goals of the Revolution, Calles sped the pace. The Mexican Congress passed the Petroleum Law, December 26, 1925, set to go into effect January 1, 1927, that not only asserted the Nation’s ownership of all oil lands but included the “Calvo Clause,” stipulating that foreigners who owned property in Mexico would no longer be able to seek “diplomatic protection from their own governments,” leaving them at the mercy of Mexican jurisdiction alone.1 The registration of clergy, prohibition on the public wearing of vestments, ban on the holding of political office as well as other regulations found resistance come to a head by 1926. Despite the diverse, and at times, subversive opinions of the Mexican bishops, it was the Vatican which decided to close the doors of Mexico’s churches, boycotting the observance of Mass, at the expense of its service to believers, in hopes of pressuring the government into full capitulation. As diplomatic relations between the United States and Mexico deteriorated on all fronts, it was not too far-fetched to imagine events may be leading directly to open war with our southern neighbor. President Wilson had deployed troops across the border in 1914, with less than decisive results. A much more disastrous and costly engagement could erupt as spring became summer in 1927, needlessly sacrificing lives on both sides, unraveling the the hard work done to achieve calm restoration at home and neighborly partnership abroad. It was then that President Coolidge made a decision that was only ever his to make. He would send a new Ambassador to Mexico, his fellow Amherst graduate, long-time ally and masterful problem-solver, Dwight Morrow.

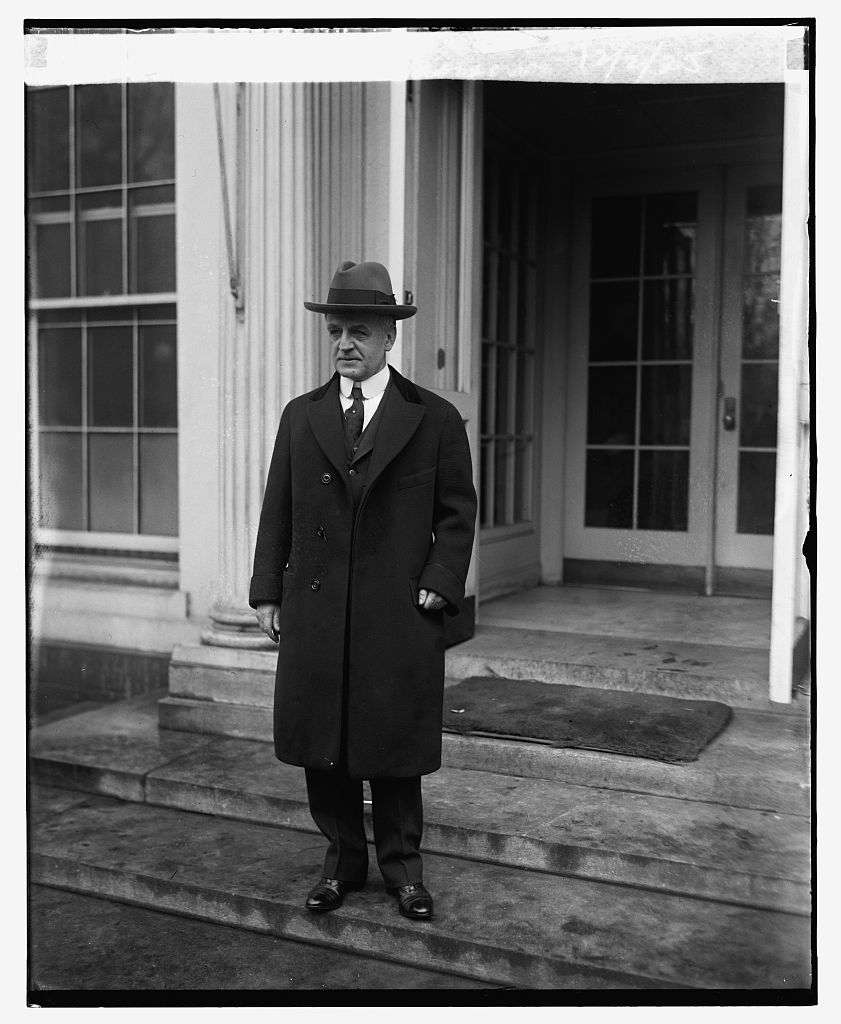

Discussing the appointment in South Dakota late in August 1927, Morrow would begin preparations for his assignment immediately, meticulously studying all he could obtain about the range of problems concerning the two nations. He carefully researched the source of the conflict as well, the Constitution of 1917, the Petroleum Law, the history of pending claims, Mexican finances and court decisions. Back in April, President Coolidge had already begun to prepare the ground for a new direction in the approach to Mexico, declaring that the United States would continue to protect its citizens abroad but not impugn the authority of Mexican legislature on the matter. Coolidge was laying the groundwork for a dynamic departure from business as usual. The days of “Dollar Diplomacy” were numbered. Coolidge, trusting Morrow to know his task well, gave no other instructions save, “Keep us out of war.” Coolidge knew Morrow would figure out how best that should be done. Formally appointed in September, the Morrow family would arrive on October 23, 1927 in Mexico to begin the new Ambassador’s work. His thorough study had identified four basic problems: 1) Oil; 2) Land; 3) Claims; and 4) Debts. Morrow would tackle each in a unique way but our main focus here centers upon oil and the Church-State conflict. As Mar Rubio has noted, investment in oil had been falling since its peak in 1921, to its lowest point in ten years when Morrow arrived.2 Mexico had supplied twenty-five percent of the world’s petroleum and stood right behind the United States in oil exportation. It would furnish a mere three percent of world supplies by 1930. This effort by the Coolidge administration meant far more than the value of oil. It was about peaceful relations with one of our closest neighbors. Meanwhile, Coolidge would confirm the seriousness of his determination to correct past mistakes by conversing directly with President Calles over newly installed telephone lines between Washington and Mexico City. Calles, too, had expressed a desire to repair the damage between the two nations. Without both sides being ready to reason together, the circumstances would not have been ripe.

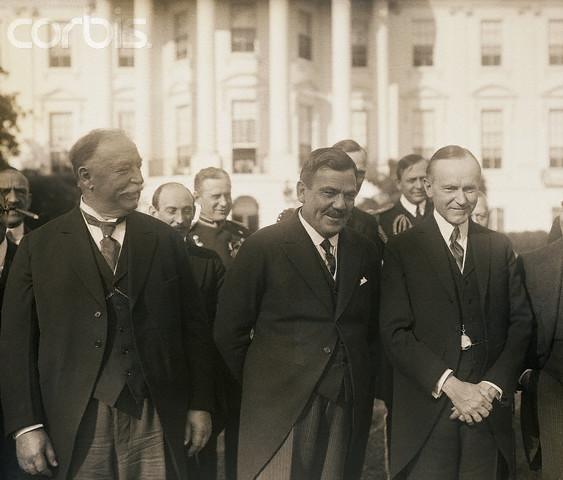

Chief Justice Taft, Mexican President Calles and President Coolidge, during the visit of Calles to America, 1925. When the large Justice Taft was asked by the photographer to move in closer, he turned to Coolidge and said in self-deprecating fashion, that would likely crowd out Mexico, which is something we would never do. To that Coolidge and Calles are photographed chuckling at the joke. Courtesy of Corbis.

Contrary to the film’s portrayal, Morrow did not disembark from the train and begin talking issues with Calles. Morrow would not only sidestep diplomatic protocol to deal directly with Calles, he would stop by the various Ministries and visit with officials whenever time allowed. Bringing his own small team of trusted confidants, Morrow ensured that he would learn all the facts without institutionalized filters of suppressed and tainted information. Working at a time when Soviet envoys, diplomatically recognized by Mexico since 1924, were present in the capital city, there was no shortage of espionage and counter-propaganda when Morrow arrived. That quickly changed.3 The embassy, suspicious and uncertain at first, came to marvel at Morrow’s ability to fix issues that had been deemed un-fixable for ten years. Morrow had to first build trust and credibility after years of subterfuge and hostility between our ambassadors and the Mexican government. Morrow would begin by hosting President Calles to ham and egg breakfasts, meeting three times before Calles finally broached the subject of oil. Calles wondered how the ambassador perceived a solution to this long-standing diplomatic problem. Morrow’s answer arrested the President’s attention and began a long confidence in the American ambassador’s judgment. The problem was not diplomatic, Morrow stated matter-of-factly, it was a question of law.4 Article 17 of the 1917 Constitution was clear that no law could be retroactive. It had been on that basis that the Mexican Supreme Court had ruled the ownership of oil lands could be not confiscated retroactively, hence the Petroleum Law violated the nation’s own Constitution. The forfeiture of lands whose leases had not been renewed by January 1 of that year, could not simply be taken by the government. The Ministry of Industry and Commerce, was violating both constitutional and municipal law, Morrow said. With this Calles could not disagree. It was not the conventional American position: you do this or we invade; you do this or we accuse you of international law violations. Mexican law precluded this extra-constitutional land seizure program. To Morrow’s astonishment, it would be less than two months before the Mexican Supreme Court had ruled the Petroleum Law invalid and the Mexican Congress, at the request of President Calles, abandoned the “Calvo Clause” and reaffirmed property rights if the land in question was already under development. By March of 1928, the State Department, with no little amazement, announced the question of foreign property rights solved. Morrow stood high in the estimation of those on both sides of the border as a result. However, he was not done yet.

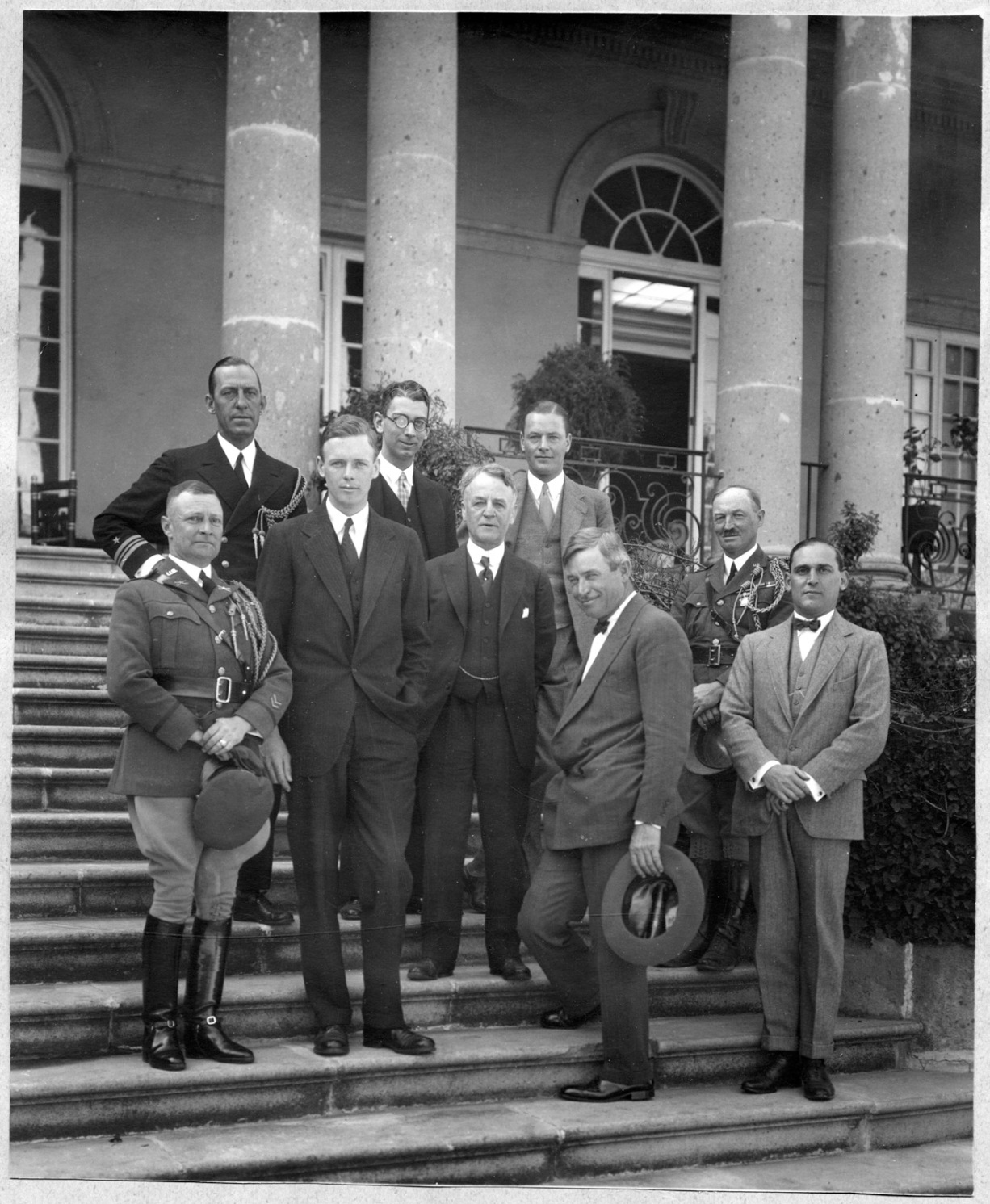

Ambassador Morrow, with some of his specially-chosen team of American envoys, including aviator Charles Lindbergh and humorist Will Rogers, Mexico City, 1927. Source: http://consecratedeminence.wordpress.com/2014/03/16/the-lone-eagle-meets-the-ham-eggs-diplomat/.

Morrow had to continue building trust with Calles if any resolution was to come from the ongoing turmoil between the government and the Catholic Church. In this Morrow had to employ multiple approaches working simultaneously. The most difficult personal risk came when he agreed to accompany Calles on his tour of northern Mexico. Angering Catholic activists in the United States, who felt he had betrayal their cause, Morrow traveled with Calles, accompanied by Will Rogers in fact, to win the proud President’s faith. It allowed Calles to assert his independence from American intervention and in exchange, Morrow secured a platform of credibility that enabled the churches to reopen, the Calles Laws to quietly go away, and the Cristero War to end. The issue was too sensitive to ride in on a conventional interventionist tack and dictate how it was going to be. Morrow had be strategic if the fighting was to end on terms agreeable to both sides. As Spenser puts it, “This appearance of not exerting any pressure on the Mexicans was precisely one of Morrow’s achievements: to avoid the appearance that he was really exerting pressure on the Mexicans.”5

This was not the old game of deception and domination, Morrow had no condescension, a sense of superiority dealing with inferiority. If the problems between these two sovereign nations were to find resolution, we had to regard one another as equals. Consequently, Morrow approached Mexico as a partner, not a subordinate. Its laws were the laws of a sovereign nation, whether Americans agreed with them or not. America would have to respect the rule of law abroad just as it did at home. Improvement in relations could not come through disrespect of that rule, even in the effort to help people. If the law needed to change, it would have to change within the framework of Mexico’s institutions. Morrow was a genuinely humble and benevolent-hearted man. He loved Mexico and consequently won the Mexican people with his boyish curiosity and consistent openness with all. He even recruited his future son-in-law, Charles Lindbergh, to foster a healthy dose of good will by requesting a special flight into Mexico City in December 1927, to the admiration and fascination of the people in both nations. Still, not all Catholics were acting from honorable motives, as the conduct of Father Vega illustrates. Tuck observes that it was the brutal attack on the train in early 1927, that led to the harshest responses by the Federalistas.6 Until then, Calles had been implementing a gradual escalation of enforcement. The film conveys nothing of this. Rather, it leads the viewer to assume that the government showed up one day and began mowing people down while “at church.” Bailey7 and even Meyer8 show that Vega deliberately burned the train with civilians as retaliation for the death of his brother, himself a merciless soldier in the Cristero army. The Mexican bishops, even the Cristeros themselves, had networks of propagandists and schemes. The movie, decidedly favorable to the Catholic Church exonerates Vega and glosses over the eighteen months of intransigence by the Vatican when all other parties were prepared to reconcile on the terms worked out between President Calles and Father Burke, facilitated by Ambassador Morrow.9 The movie also never mentions the radical underground led by Madre Conchita, who inspired young Catholics to resort to bombing and assassination in order to overthrow the government, in the midst of the Cristero War.10 One of them, Jose de Leon Toral, succeeded in the second attempt to kill the in-coming President Alvaro Obregon, at a critical moment when the conflict seemed about to resolve and a constitutional transition of power from Calles to Obregon was at hand. Another of Madre Conchita’s disciples bombed the Chamber of Deputies, demolishing the chambers but hurting no one. These actions were only thwarting Mexico’s recovery.

This is not to indulge in the same bashing of Catholics as some have done. These instances show that both camps had villains and it is all the more incredible that Coolidge’s ambassador successfully navigated a path to reconciliation.11 With Calles not constitutionally allowed to serve another term, and Obregon murdered, the crisis devolved around who would assume the government, avoiding further loss of life and lawlessness? Finally, the talks between the government and Father Burke agreed that the churches would reopen and services would resume, unencumbered. Registration would only be done if requested by the bishops, a move virtually taking the teeth out of Calles Law enforcement. The Cristeros would have to lay down their arms and calm finally returned with the clang of church bells, announcing the reopening of Catholic services throughout Mexico, June 30, 1929. Turning to Mrs. Morrow on that occasion, he asked, “Do you hear that? I have opened the churches in Mexico.” As the noise continued and increased for several minutes, he again turned to her and said with a smile, “Would you now like me to close the churches in Mexico?”12

By this time, Morrow had helped Calles back off from his unfettered socialism and he began a shift as a more conservative counterweight to Cardenas in the 1930s. Calles would even begin to look statesman-like as it became increasingly clear that the administration of Portes Gil, his successor as President, needed to fire two department ministers, who were dragging the government back down the path of ignoring Mexican law regarding land once again.13 Until cooler heads prevailed, the new administration was rushing headlong into new indebtedness by demanding more land be nationalized than Mexico’s annual budget could handle. Tying Mexico’s fiscal solvency to the rate of socialism was one of Morrow’s shrewdest recommendations to Calles, proving to be an effective means of slowing radical changes and allowing time to be bought for calmer policies to prevail at a pace that would not leave the country further divided and class-driven. Morrow had a profounder impact on Calles than either could have realized. Yet, through it all, he simply sought to solve the problem for the best of all concerned. He cared nothing for glory or recognition. As he would tell his son, “The world is divided into people who do things and people who get the credit. Try if you can to belong to the first class. There’s far less competition.” As Norman Davis says, Morrow belonged to both classes.14 For all the film’s heroes, two of them are glaringly marginalized, Morrow and Coolidge. The important part played by these men is missing from the film. For Greater Glory presents a poorer narrative for failing to do so, failing to convey a fuller understanding of men determined to craft peace outside of old, conventional modes of thinking. Morrow is a credit to his country and a powerful demonstration, at its very finest, of the Coolidge approach to foreign policy in action. It rested on something more than material forces. It is an affirmation of Coolidge’s courage and sound judgment that Morrow accomplished far more than what could be secured by mere force of arms or diplomatic convention alone.

Endnotes

1 Harold Nicholson, Dwight Morrow, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York, 1935, p.327.

2 Mar Rubio, “Oil and economy in Mexico, 1900-1930s.” Essay, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, 2003.

3 Daniela Spenser, The Impossible Triangle: Mexico, Soviet Russia, and the United States in the 1920s, Duke University Press, Durham, 1999, pp.139, 143.

6 Jim Tuck, The Holy War in Los Altos: A Regional Analysis of Mexico’s Cristero Rebellion, University of Arizona Press, Tuscon, 1982, p.65.

7 David C. Bailey, ¡Viva Cristo Rey! The Cristero Rebellion and the Church-State Conflict in Mexico, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1974, p.141.

8 Jean A. Meyer, The Cristero Rebellion: The Mexican People Between Church and State, 1926-1929, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1976, pp.61, 121, 168-9.

9 L. Ethan Ellis, “Dwight Morrow and the Church-State Controversy in Mexico,” The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 38, No. 4 (Nov., 1958), pp. 482-505.

10 John W. F. Dulles, Yesterday in Mexico: A Chronicle of the Revolution, 1919-1936, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1961, pp.363ff.

11 Jurgen Buchenau, Plutarco Elias Calles and the Mexican Revolution, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, 2007, pp.145, 153.

14 Norman Davis, “Dwight Whitney Morrow.” Lecture at Englewood Public Library, Englewood, New Jersey, 2006.