“No American coming to Philadelphia on this anniversary could escape being thrilled at the thought of what this commemoration means. It brings to mind events, which in the course of the century and a half that has passed since the day we are celebrating, have changed the course of human history. Then was formed the ideal of the American nation. Two years later this was put into practical effect by the Declaration of Independence. Here too was prepared and adopted the Federal Constitution, guaranteeing unity and perpetuation of our national life…”

The anniversary to which Calvin Coolidge was referring ninety years ago today commemorated the meeting of the First Continental Congress on this same day, one hundred and fifty years before. It marked the first time that the Colonists, after more than two decades of escalating hostility from their King and Parliament, came together to collaborate in constructive and unified action, to appeal to the reason of all free people and to defend their liberties against the subtle and insidious encroachment of government loosed of its lawful limits. Reflecting on the men who bravely took that first great step and what they did at severe risk to themselves has much to teach us, Coolidge declared. Tyranny, most of all in republics, does not happen overnight. It comes by a series of incremental pretensions to which it is easier to comply and acquiesce than challenge and refuse while those violations are still slight and few. Left unanswered, the abuses grow and those who exploit them embolden until the population finds itself shackled in servitude through its silent tolerance of freedom’s erosion. Coolidge reminds us what made them extraordinary. “They were men of faith. They believed in their cause. They trusted the people. They doubted not that a Higher Power would support them in their effort for right and freedom…they still rank as a most remarkable gathering of men. Their deliberations and actions are worthy of the most careful study by the American people. If we could better understand what they said and did to establish our free institutions, we should be less likely to be misled by the misrepresentations and distorted arguments of the hour, and be far better equipped to maintain them.” The cynicism of today toward these men and the institutions they confirmed for posterity is not grounded in a thorough acquaintance with them, a knowledge of something more than what has been spoon-fed to us, but rather in a shallow-rooted (and close-minded) certainty that textbooks tell us all there is to know. No further curiosity is needed or sought. Who needs wisdom when you have knowledge? Who needs logic when you have trivia? In short, we are trained by the delusion that our ignorance has actually empowered us, making us independent thinkers when we are not thinking for ourselves at all.

Coolidge resumes, “[T]he principle which the people declared was of supreme importance…[T]hey had no hesitation about making a plain statement of the truth, because they politely observed, ‘as Your Majesty enjoys the signal distinction of reigning over freemen, we apprehend the language of free men cannot be displeasing.’ “ Personal and public freedom meant nothing if they could not publicly speak the truth and, when necessary, speak it to the highest authority of human government. To free people, even Kings are not above giving account of themselves. The First Congress, by balancing candor with restraint, not only avoided giving place to distortion and accusation but strengthened the reasonableness of their cause. “It is easy to draw broad indictments or indulge in sweeping promises,” Coolidge observed. “It is no trouble to indulge in invective. But denunciation does not provide a remedy. In moderation and restraint is much more likely to be found a way to agreement upon constructive measures.” Make no mistake, Coolidge says, the participants in the First Congress, from the Adamses to John Jay, were not pandering moderates, they were revolutionary conservatives, appealing to the moderation and restraint in the logic of their principles. Coolidge explains further, “Appeals to violence and hatred in the first Continental Congress might have produced a rebellion, but they could not have accomplished revolution. They might have led to war, but they could not have secured victory.”

The pivotal nature of this first great collaboration is seen in what Coolidge said next.

“Almost all our history as an independent and united nation can be traced back to the assembling of the first Continental Congress, which we are met to celebrate. Our achievements have been wrought by adherence to its policies of reason and restraint, accompanied by firmness and determination…The case which the Congress stated was unanswerable. One side or the other must either give way or maintain its position by force of arms. That conflict for which the Congress had laid the logical foundation was not long in beginning. Liberty never won a more substantial and far reaching victory than that which resulted from our Revolutionary War…The idea of a republic was not new, but the practical working out of such a form of government under separate and independent, and yet well balanced departments, was a very new thing in the world. The governments of the past could fairly be characterized as devices for maintaining in perpetuity the place and position of certain privileged classes, without any ultimate protection for the rights of the people. The Government of the United States is a device for maintaining in perpetuity the rights of the people, with the ultimate extinction of all privileged classes.”

Coolidge saw no disparity between the purpose for which the Revolution had been fought and the establishment of its practical ideals in the Government inaugurated in 1789. The Declaration and Constitution were not at odds with each other, not parchments of two conflicting visions but one, continuous thread of logic binding both together as the latter a reasoned consequence of the former. Just as the “first Continental Congress met to redress grievances which were the result of government action” so the “Revolution was fought to resist those same grievances. And finally, the Constitution was adopted to prevent similar impositions from ever again being inflicted upon the people.”

Coolidge made clear that the remedies for future abuses are anything but housed in some obscure archive somewhere or somehow out of our hands. The means of redressing violence to our freedoms and institutions remain immediately before us, they are right in the Constitution itself. Those “priceless guarantees,” as Coolidge called them, “are all in that precious document.” As demonstrated by the First Congress, however, the power of these principles exists in our will and our ability to make use of them. The very last vestiges of freedom, like any muscle in the body, shrinks and languishes with disuse.

“The people do not propose again to entrust their government to others, but to retain it under their own control. No one can tax them or even propose a tax upon them, save themselves and their own representatives. Instead of encroaching upon local Assemblies, it guarantees each state a republican form of government. It regulates suspension of the writ of Habeas Corpus. it protects the home from the uninvited intrusion of the military force of the Government. It guards the right of jury trial and undertakes to make judicial officers independent, impartial and free from every motive to follow any influence save that of the evidence, the law and the truth. These are representative of the great body of our liberties, of which the Constitution is the sole source and guarantee.”

President Coolidge understood that these liberties are ours only insofar as we exercise them. If they are neglected and taken for granted, we will find them gone when in most dire need of them. The First Congress did not wait for those freedoms to be stripped away or for someone else to act on their behalf before decrying the injustice of even slight government abuse. It was experience that had taught them a rational skepticism toward unquestioned compliance with arbitrary governance, authority devoid of responsibility, and a reliance in wise experts to administer our freedoms better than we can ourselves. Coolidge hammered the point home.

“Ours, as you know, is a government of limited powers. The Constitution confers the authority for certain actions upon the President and the Congress, and explicitly prohibits them from taking other actions. This is done to protect the rights and liberties of the people. The Government is limited, only the people are absolute. Whenever the legislative or executive power undertakes to overstep the bounds of its limitations, any person who is injured may resort to the courts for protection and remedy. We do not submit the precious rights of the people to the hazard of a prejudiced and irresponsible political determination, but preserve and protect them by an independent and impartial judicial determination. We do not expose the rights of the weak to the danger of being overcome in the public forum by popular uproar, but protect them in the sanctity of the courtroom, where the still, small voice will not fail to be heard. Any attempt to change this method of procedure is an attempt to put the people again in jeopardy of the impositions and the tyrannies from which the first Continental Congress sought to deliver them. The only position that Americans can take is that they are against all despotism whether it emanate from a monarch, from a parliament, or from a mob. A significant circumstance of the First Congress, one which ought never to be overlooked, lies in the fact that it resulted from the voluntary effort on the part of the people to redress their own grievances and remedy their own wrongs. We pay too little attention to the reserve power of the people to take care of themselves. We are too solicitous for government intervention, on the theory, first, that the people themselves are helpless, and second, that the Government has superior capacity for action. Often times both of these conclusions are wrong.”

The lessons of what has now become known as the Progressive Era, the period just coming to a close as Coolidge came to national office, afforded helpful direction on this front. The perceived abuses that had fueled the intervention of government may have been helpful at times and in certain locales. It may yet be necessary, Coolidge granted, but it was a serious mistake to believe that intervention, once introduced, was “always wisely administered.” The Progressive Era had not been so progressive or successful, as it appeared it would be at its inception. In the effort to curtail wrongdoing, “its restrictions often hamper development and progress, retard enterprise” and bring government, as it is supposed to function, into disrepute. “The real fact is that in a republic like ours the people are the government, and if they cannot secure perfection in their own economic life it is altogether improbable that the Government can secure it for them.” Given this reality – that in America the people are sovereign, “capable of owning and managing their own government” — how can anyone credibly maintain that those same people are incapable and unable “to own and manage their own business”? Coolidge’s example of keeping utilities outside of Government middle men, owned instead by the tens of millions of Americans who invest in its growth and maintenance, validates the principle insisted upon since those early days of the Continental Congress.

“Our forefathers were alert to resist all encroachments upon their rights. If we wish to maintain our rights, we can do no less. Through the breaking down of the power of the courts lies an easy way to the confiscation of the property and the destruction of the liberty of the individual. With railways and electrical utilities under political control, the domination of a group would be so firmly entrenched in the whole direction of our Government, that the privilege of citizenship for the rest of the people would consist largely in the payment of taxes. The Fathers sought to escape from any such condition, through the guarantees of our Constitution. They put their faith in a free republic. If we wish to maintain what they established, we shall do well to leave the people in the ownership of their property, in control of their Government, and under the protection of their courts. By a resolute determination to resist all these encroachments we can best show our reverence and appreciation for the men and the work of the first Continental Congress.”

Closing his address to all those gathered this day, ninety years ago, President Coolidge left his audience with the reminder that the best commemoration of this day and the work that was begun — now two hundred and forty years later — is observed when we make full use of our freedoms and kindle again that alert resistance to government’s penchant to encroach on them. The experiences of the First Congress serve as a warning that “small infractions” can demolish “great principles of liberty.” However, it also carries a hopeful reminder that though “any kind of tyranny” can follow an abandonment of the integrity of our courts, tyrants cannot withstand the resolute determination of a united, watchful and sovereign people.

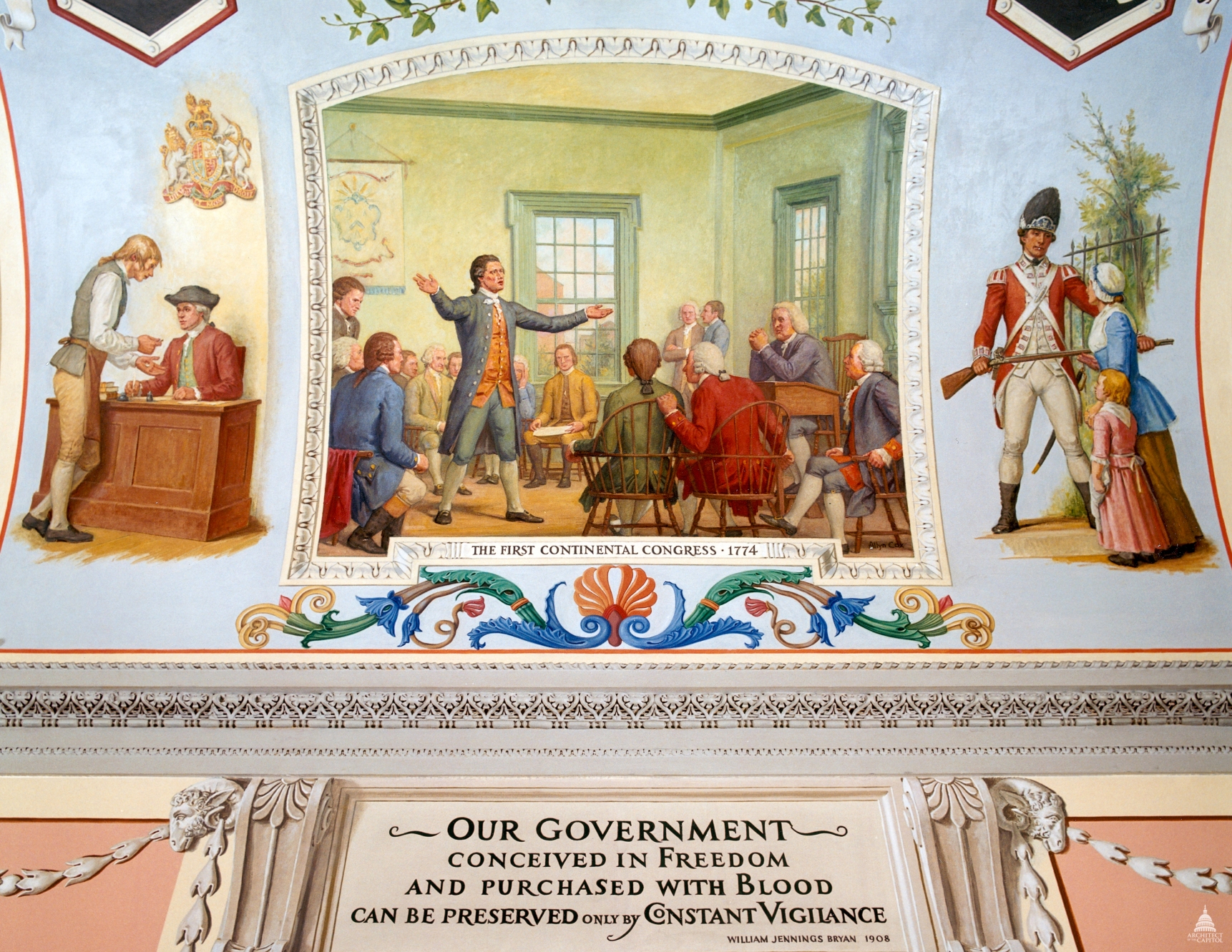

Carpenter’s Hall, where the first Continental Congress met, September 25, 1774. President Coolidge commemorated the 150th anniversary of that meeting here in 1924.