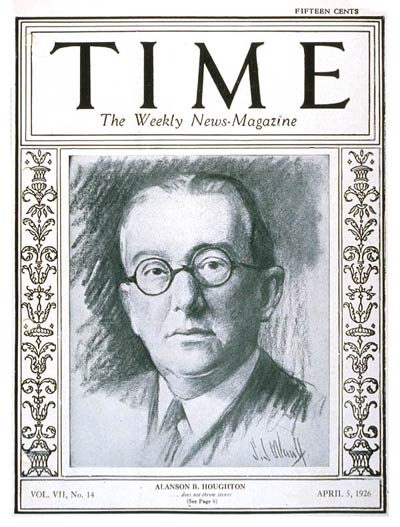

Eleven years ago Dr. Jeffrey J. Matthews, currently Professor of Business and Leadership at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington, launched out on the first of what have since become three fascinating books on leadership. His first work, published in 2003, ventured into previously untraversed territory with a biographical study of Alanson B. Houghton, America’s foremost ambassador during the Harding and Coolidge Era. Up to that time, there had never been an attempt so focused on reacquainting Americans not only with Ambassador Houghton but with his perspective on the “conservative internationalism” of the 1920s. Harding appointed him America’s first post-War envoy to Germany, Coolidge promoted him to the preeminent diplomatic post in Great Britain, and Hoover, whose disdain for Houghton was no secret, let him retire to anonymity after seeing him lose his race for U.S. Senator from New York.

Dr. Matthews, making diligent use of Houghton’s papers and never-published diary, reveals more than the competent entrepreneur of Corning Glass Works but also the dedicated public servant and conscientious critic who exercised pivotal influence on every major foreign policy accomplishment of that most active of decades. The Washington Disarmament Conference, the Ruhr Crisis, the Dawes Plan, the Locarno Treaties, the Geneva Conference, the Young Plan, and the Kellogg-Briand Pact are all explained and Houghton’s part in preparing the ground for their development and implementation each feature a central place in the book. The author includes a very useful timeline of Houghton’s life and career from his birth in 1863 to the attack on Pearl Harbor, less than three months after his death. The outbreak of World War II in Europe, a travesty Houghton not only predicted years before but strove mightily to prevent, shattered his spirit. It seemed to a repudiation of all he had tried to accomplish, an undoing of all he had worked for over the course of thirty years in business and public service. By then, of course, a much different policy had been adopted and the “first steps” taken to protect peace in the 1920s had long been rejected. It was not because his generation had somehow failed to do enough or try enough to avoid them. Peace is only ever as secure as each new generation resolves to attain it and build upon it. The prevention of war all through the 1920s into the early 1930s is a testament to something resilient, something worth learning from in what Houghton, President Coolidge and the rest of his administration built.

Dr. Matthews’ work is written from what historians have come to call the “revisionist” view, which largely means the body of scholarship that has challenged the accepted narrative that the Twenties were naively isolationist, Coolidge never did anything besides sleep and crack jokes while the laissez-faire policies of Mellon and company led directly to the Great Depression and, by extension, World War II. As such, Dr. Matthews makes an invaluable contribution to restore proper scholarship and a long-overdue correction of the record. However, Matthews’ book has limits. He makes a recurring case for the sharp differences between Ambassador Houghton and the Coolidge administration. Yet, each conflict, when examined more closely, must admit that President Coolidge really had no substantial disagreement with Houghton at any point. The author, along with Houghton himself, seems to need regular reminder that he is the administration. Coolidge chose him to do the job, knowing his talents and judgment would equip him for articulating the policy of the administration. The President expected this of all his appointments, delegating responsibility for the details while he set the overall goals and objectives. The best case Dr. Matthews can make is for the divergence between Coolidge and his ambassador in policy priorities at the Geneva Conference, but even then Coolidge tactfully decides what direction policy will take. In fact, Coolidge promoted him to the most prestigious diplomatic post for this very reason: Houghton was competent and thought for himself. Consequently, Coolidge consistently backed him against the meddling of Secretary Hoover, the blusters of Secretary Kellogg and the tempestuous attitudes of Britain, France, and Germany. Hoover did not set foreign policy. As Matthews later points out, Coolidge once opined, Hoover “had given him unsolicited advice for six years, all of it bad.” Not so with Houghton. The prudent Ambassador was a loyal and reliable subordinate. His one major blunder of holding the press conference that aired his dissent with Kellogg being the exception to the rule.

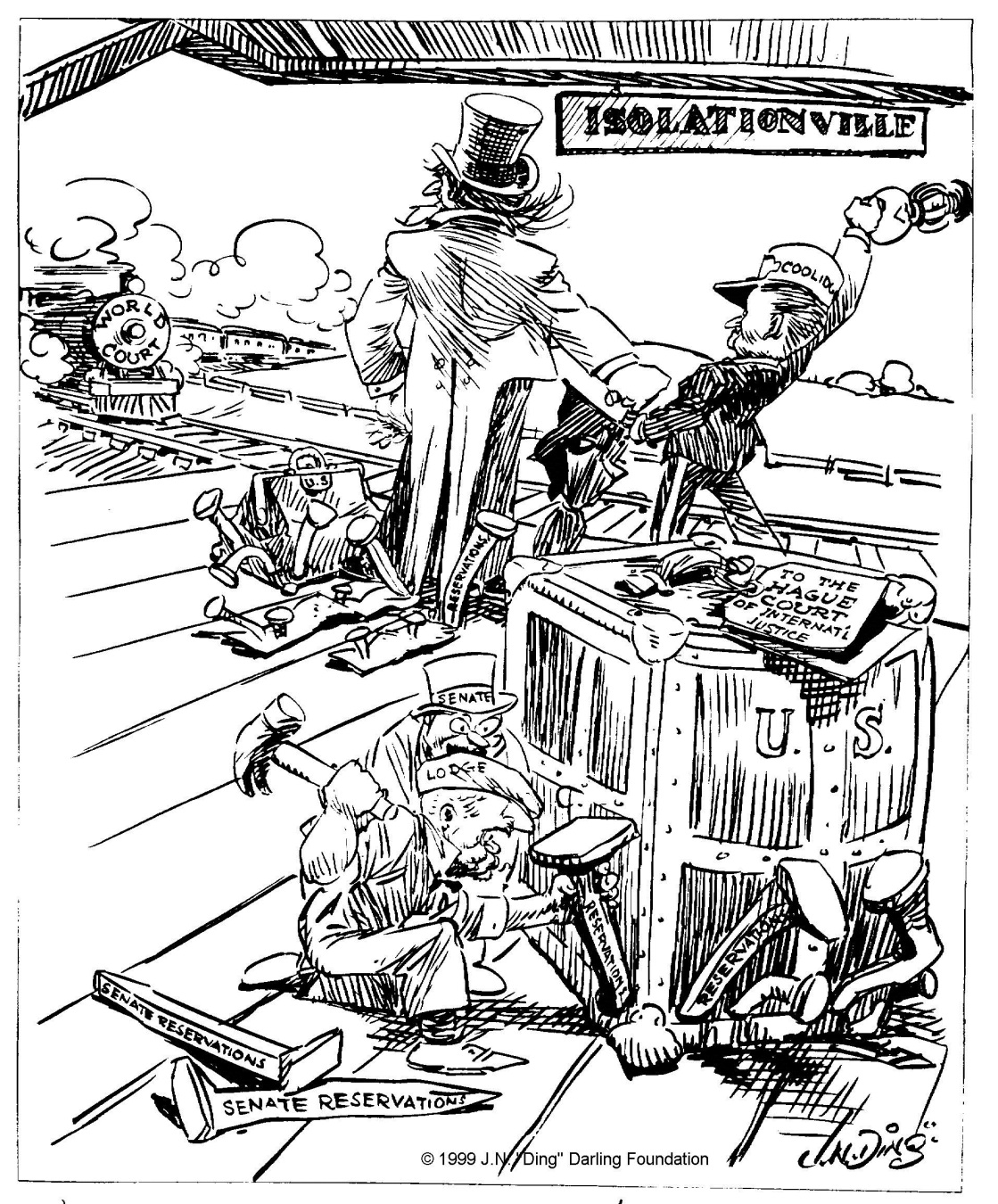

“Begins to look as if we never would get out of this jerkwater town,” cartoon by “Ding” Darling, The Des Moines Register, May 26, 1924. Courtesy of the Ding Darling Foundation.

Matthews’ book is, for the most part, very readable. His style is meticulous but not dry. His major fault surrounds his summaries at the end of each chapter. It is as if Matthews forgets some of the crucial details he has covered beforehand and omits them in his rush to harp on those pesky differences between Houghton and the administration the ambassador represented. He seems to forget where he was going with the points being made at times. Still, he has the talent of narrating a compelling life story with plenty of insight on the challenges and triumphs of Coolidge’s foreign policy. The essential difference between Houghton and Coolidge rested on whether Europe constituted a “vital” role in America’s national interests. The experiences of the late War had convinced both of the historic obligation the United States now possessed as a world power, yet Coolidge, who held a far better sense on the temperament and needs of the country, disagreed that we shared had to assume Europe’s burdens as our own. Both Houghton and Coolidge agreed that Latin America was a different story. Other differences from debt cancellation to disarmament negotiation were matters Houghton deferred to Coolidge, as his Chief and the final authority on administration policy.

His excellent rapport with the President makes it all the more fascinating when it comes to Hoover’s nomination and election in 1928 in Matthews’ book. Houghton, seeking to block the selection of Hoover, found the camp too divided between multiple “anti-Hoover” candidates that the eventual victory of Hoover was decisive despite Coolidge’s unenthusiastic response to his successor’s rise. Coolidge’s effusive commendation of Houghton, upon his resignation as British ambassador, was a distinction not lost on contemporaries. Houghton, virtually drafted into running for United States Senator from New York, found defeat not because of some deficiency in his credentials or personality but due to the overconfidence of his managers and the Republican Party in New York. Houghton did make the mistake of agreeing to campaign for Hoover in the Midwest, as he had so ably done for Coolidge in 1924, despite an already abbreviated campaign schedule. As such, he helped Hoover win while losing his own bid. It is telling as well that Hoover never attempted to reward Houghton with any of the positions he clearly merited after serving so ably in Europe through some of the most difficult problems following the War. Houghton and his wife would finally step out of the limelight and into the quiet of private life. Watching the events of the 1930s, however, was anything but restful. When a new war finally came at the close of that decade, Houghton felt a depth of sorrow for his country and the nations of Europe he had never known before. He was gone before the Japanese attacked.

The push to publish his diary, honoring his crucial part in crafting a coherent and principled foreign policy, was quickly swept aside when his sympathetic views of Germany opposed to the reckless pressures of France and Belgium in 1922 came to light. Unfortunately, Houghton’s impressions, accurate as they were at the time, ran up against current events in Germany and the rest of Europe in 1941. Houghton was regrettably shoved into the shadows by events over which he and his contemporaries from President Coolidge on down had no part and no control. Sadly, a very insightful life with all its lessons learned conflicted with the times as they now stood. It would be left to Dr. Matthews to finally return to this most neglected of central figures in American foreign policy during the Coolidge Era.