Then-Vice President Coolidge presiding over the Regular Meeting of the Business Organization of the Government in Harding’s absence, January 29, 1923.

Most of us can certainly remember a meeting from which we were relieved to be released, an occasion that left us asking what was the point of that? By January of 1928, as the Fourteenth Regular Meeting of the Business Organization of the Government convened in Washington’s Memorial Continental Hall, the Nation’s stellar economic growth along with another Budget surplus for the coming year left many wondering how important these meetings actually were when so much “spending money” was coming into Government coffers. Since the Government continued to operate in the black, even after an upturn in expenditures following the devastating floods of the previous year, it seemed as if surpluses had come to stay, constructive economy had become permanently fixed in the foreseeable future, and living within one’s means was not such hard work after all. President Coolidge was making it look easy for the Government’s fiscal house to remain on the plus side. After seven years under the Budget and Accounting system it was almost being taken for granted the very difficult task and exacting discipline required to keep economy going strong.

The President, aware of this growing perception, focused attention to why these meetings were held, what their purpose was, and how the work upon which which they rested remained the very reason that prosperity persisted so strongly while retaining enough to meet not only the unexpected but also the times when spending was necessary and constructive for the country. To Coolidge, there was a time to spend just as there was a time to save. It was not an excuse to appropriate every project that came along any more than it was a basis for never saying “yes.”

“Nearly everyone,” the President began, “connects” these biannual meetings “with economy in Government expenditures. But that is not the real answer. The orderly and proportionate use of the resources of the people of the United States is certainly being sought. But that is only the method and the means of accomplishing our main object.” What was that main object? The President answered,

“The real purpose is nothing less than the true and scientific progress of humanity. It is the major effort in undertaking to establish the correct relationship between needs and resources. It works out into conservation of human energy. It is immediately translated into concrete results, not only for the people at large but for the people in the Government service. For the unemployed it makes the prospect of employment more certain. For the employed it makes hours shorter, tasks lighter, wages higher, and positions more permanent. It makes the cost of food and clothing less. It reduces rents. It makes the home easier to buy, and, having been bought, easier to pay for. It makes investments give better returns and increases the opportunity for saving. The margin for the comforts, and even the luxuries, of life is widened. The ability comes for broadening educational advantages. Leisure is secured for the better appreciation of literature, music, and art. Means exist for the ministrations of charity. Contentment and peace of mind come under these conditions, because people have the feeling of success and the consciousness that they are rising superior to their environment. Our efforts are not based on any mean and sordid materialism, but are inspired by a desire to promote the mental, moral, and spiritual welfare of the people.”

This was the actual meaning of the Budget system inaugurated seven years before. “If it is not worth working for, then I do not know anything that is worth working for.” Had the Federal Government not saved when it could have spent, paid down debts when it could have borrowed more and remained disinterested when it could have played favorites, the welfare of the whole people would never have seen the exceptional results, spiritual as well as material, the country was experiencing. Coolidge, never forgetting himself, resolved not to allow the partners in this great endeavor to lose sight of the truth that it is the people who “furnish the money to run the Government. They have a right to have it run for their benefit.” Washington operated at their behest, not the other way around. The tail did not lead the head.

“And the first thing he tackled was the lock on the chicken coop,” by “Ding” Darling, The Des Moines Register, December 11, 1923. Courtesy of the Darling Foundation and the University of Iowa.

A business operation as extensive as the Federal Government encounters problems continually, and as such must be regularly reminded of the principles which anchor and direct it, Coolidge declared. That was why these meetings were held twice every six months. All that had been accomplished would be undone if a cavalier attitude were indulged in “our future operations.” Each department, each bureau, each agency had a separate part in that noble task but by seeing the effect of everyone’s role upon the overall situation, all could understand how important small, organized actions were to the final outcome. Circumstances were only making it ever more imperative that the advantage of the people — the sole focus of their work — persist on every front, from diminishing little by little the public debt to three historic reductions in taxation. Neither would have ever been achieved without a conscientious management over the Nation’s expenses.

This is all the more noteworthy, Coolidge reminded his audience, when figures are consulted. In two short years, from 1917 to 1919, the debt went from $1.25 billion to an astronomical $26 billion. After just over eight years, $8.5 billion of that had been paid back, with another $8.5 in interest retired. “This shows how much easier it is to borrow money than to pay it.” Yet, thanks to the valiant efforts of many this massive burden had begun to lighten after ten and a half years since first incurring it. This meant more than numbers on a sheet, it translated to real advantages to every home in America. It meant $1 million less per day in interest payments or, put another way, two hundred thousand people at $5 a day out of a total population of one hundred and fifty million. The discipline exercised the past eight years had “released” untold “productive employment for the good of all the people.” Coolidge exclaimed, “What a saving of human energy!”

“The conditions which made,” the President continued, tax relief “possible did not occur by accident. They were the result of carefully conducted Federal business.” The Executive and Legislative Branches had coordinated to “make this possible.” The “great good” that had come from keeping expenditures within receipts was so vast that how could any other course be entertained? How could his audience, let alone the whole people, ever tolerate any other path?

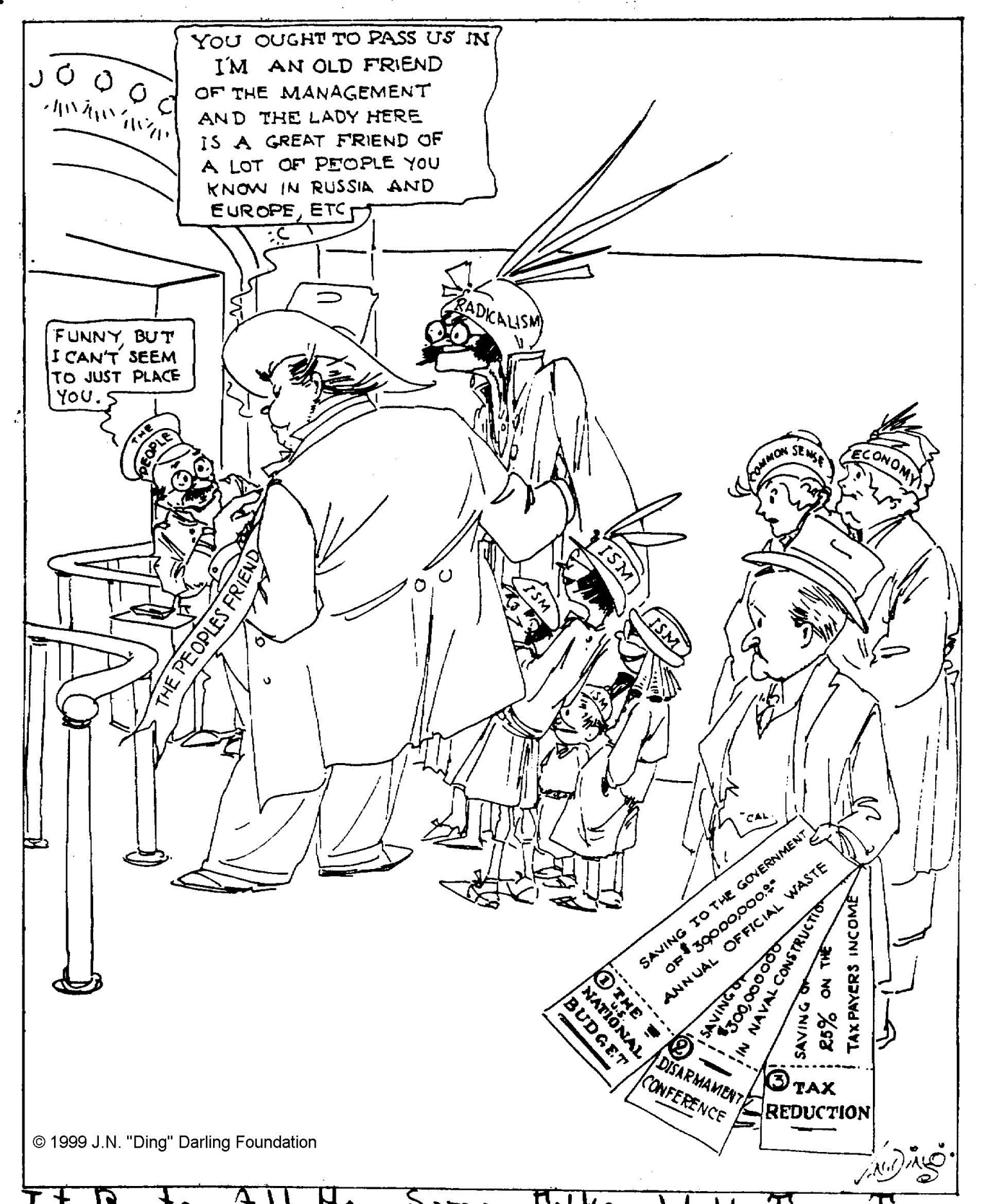

“It beats all how some folks will try to impose on a slight acquaintance,” by “Ding” Darling, The Des Moines Register, October 11, 1924. Courtesy of the Darling Foundation and the University of Iowa.

Already looking ahead to 1929, President Coolidge observed that a surplus of just over $252 million was then before the Congress in his Budget. While he saw little to threaten that surplus, he knew that danger remained if balance were cast aside and an excessive reduction in taxes became the policy. Coolidge was not so naive as to believe that continuing a steady program of tax cuts remained the universal answer for all occasions. There was a point at which tax reduction became detrimental, an evil of its own. As he put it, “It is far better to have no tax reduction than to have too much.” After all, retiring the debt was but another form of cutting down taxation. However, without tax revenue, that very positive good would end. As Coolidge would recount in his Autobiography regarding the heavy cuts in the 1928 tax bill, “As it passed the House, the reductions were so large that the revenue necessary to meet the public expenses would not have been furnished. By quietly making this known to the Senate, and enlisting support for that position among their constituents, it was possible to secure such modification of the measure that it could be adopted without greatly endangering the revenue” (p.225).

Before elaborating on the concept of benefits to keeping taxes from further reduction, Coolidge encouraged his listeners on the successes witnessed since 1923. The goal that year had set an even $3 billion as the impassable limit of annual expenditures allowed. Despite concentrated effort, another $295 million above the cap was tallied at the end of the year. It was left to the next five years to eliminate that odious $295 million. 1927 had been an especially rough one for constructive economy. So many demands were being pressed upon the Government, including an inordinately abundant number of unforeseen events, that the prospect of keeping under that $3 billion mark seemed more elusive than ever. Undeterred by millions appropriated by Congress, the resolute men and women Coolidge was addressing held fast to their work. As the fiscal year closed, expenditures stood at $2,974,000,000, what Coolidge hailed a “complete success.” It was not only possible to replicate that success, it was attainable to improve upon it.

If what Coolidge and those listening to him that evening were engaged was merely including “new and urgent requirements” to what was already being done, constructive economy would be nothing more than “mathematical addition.” Each year, as the President made plain, however, every dollar expended was given “exhaustive examination.” No program was presumed untouchable or beyond asking, “Why?” and “What for?” Only by removing the unnecessary and redundant, scaling them back where the situation warranted, could new and urgent needs be met without recourse to new levels of taxation to fund them. “This progressive and systematic examination of all of our activities must constantly go on.” This worked hand-in-hand with a reserve for unplanned costs, as the Budget system was intended, since the saving in one place enables a proportionate flexibility to meet the requirements arising somewhere else, as the law and occasion permitted.

Real economy did not mean saying “no” whatever the particulars. “True economy means the discouragement of unnecessary expenditures.” It was not through an indiscriminate refusal of all new expenditure but by taking on new needs in measured increments, “as much as possible” from the total of “prospective new requirements” that the actual meaning of economy was realized. Coolidge then waded into the specifics of beneficial spending, assessing the items entailed in national defense. Together, the costs would approach $650 million in the following year. Breaking it down further, this meant an average expense of $1,233 every minute, or $20.50 for every second in the year. The needs of facility construction would amount to $350 million, including the building of customhouses, post offices, and other structures in service to the public. Army expenditures would exact another $100 million while $10 million would go to house those who represented America, serving overseas. All this was made doable by constructive economy. Without it, no great expenditure could be maintained for any length of time. This was expensive but it was a case of beneficial expense for the Nation. The Navy’s building plans were likewise approved by Coolidge not as a means toward international competition or dependence, committing America to uncertain and dubiously financed programs, but in conformity to the principles of constructive economy. Such entailed the replacing of the obsolete and making sensible improvements where “conditions dictate[d] and Treasury balances warrant[ed].”

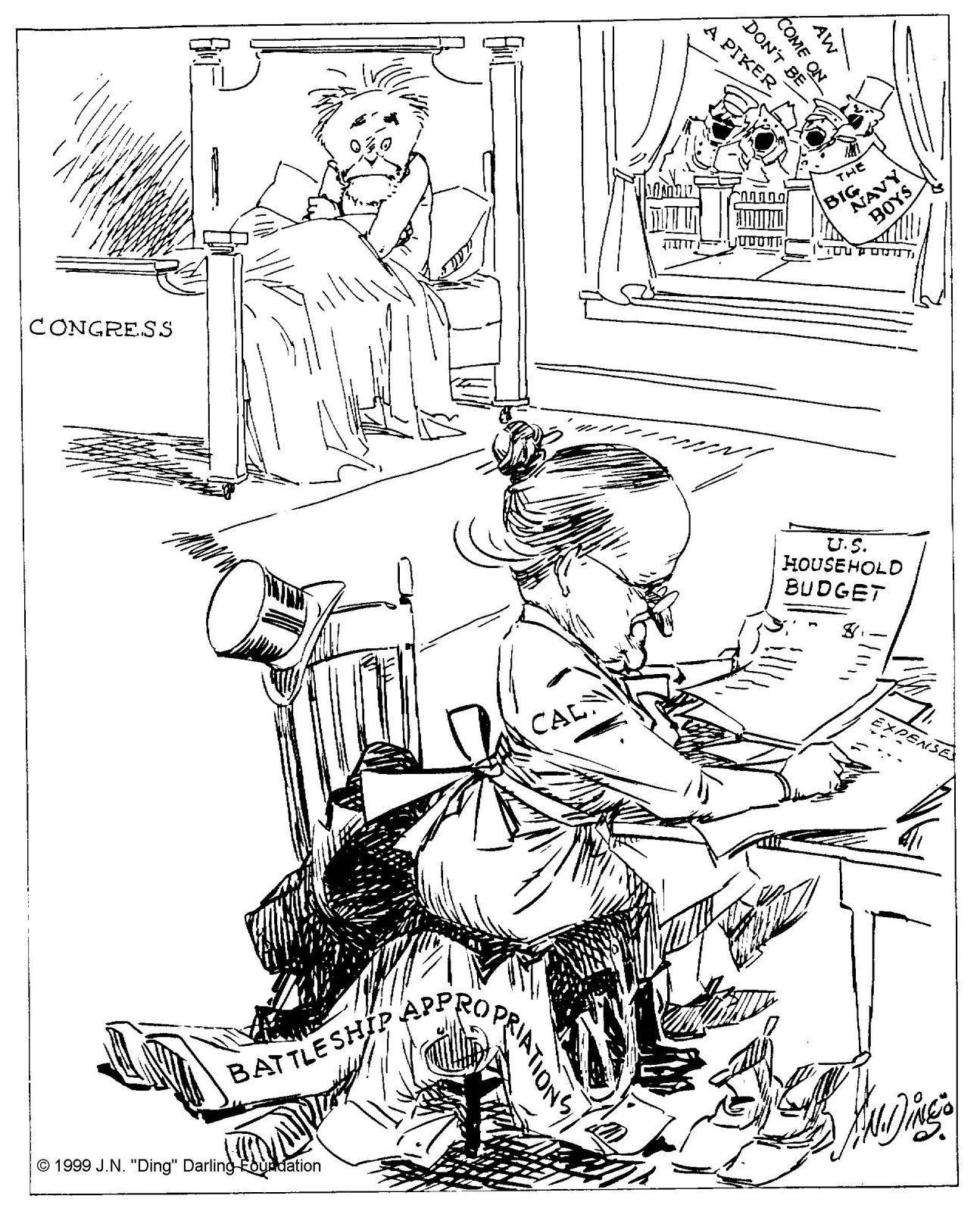

“Not much danger of his getting out on a wild debauch,” by “Ding: Darling, The Des Moines Register, February 3, 1927. Courtesy of the Darling Foundation and the University of Iowa.

As President Coolidge neared the close of his message before the Fourteenth Meeting of the Business Organization of the Government, he surveyed the challenges of the coming year. The first of these was in keeping Budget expenditures below the $3.3 billion allotted for that purpose. Estimates already held figures well within that mark, but it would be up to the men and women of the Executive Branch to make that goal a reality before the end of the next fiscal year. As they all knew well, plans and estimations are great but they need the daily adherence to constructive principles if they are to become anything more than numbers on the page of a Government report. On this basis Coolidge encouraged those present that night that constructive economy was “not a policy of negation.” On the contrary, he asserted,

“It calls for positive action…It looks ahead. It undertakes to make plans to-day for the needs of to-morrow. It is because of care in expenditure that the surplus has been accumulated which reduced our debt, which cut down our interests, which gave relief from taxation, and which has still left a margin for public buildings, for internal improvements, for national defense. All of this is preeminently constructive. As I indicated at the outset, it has brought brighter opportunities to every home in the land. If there is any one thing on which the people of this Nation should insist, it is the continuation of this policy in the handling of their national finances.”

This made cooperation and coordination between the departments and the Budget Bureau all the more essential. This was not a work turned over the consultants or highly-paid experts from outside institutions, it was carried out to completion by the people already employed in public service. Those responsible for coordinating between the various offices and the President, as his representatives, deserved all the encouragement and credit that is due their difficult charge. These coordinators were among many to whom a full appreciation to all “who have contributed to the success of the efforts for the orderly financing of our national revenues under the Budget system” would be impossible to catalog. None of this would have been successful had it not been for the people themselves, insisting on its implementation year after year, Coolidge reiterated. One wonders if the same energy had been behind Budget discipline today as was the case then, would we be on the way to paying down an even more astronomical debt than Coolidge ever imagined? Still, it is needful to remember that the adherence to the Budget system was not a one-man operation.

President Coolidge concludes his address recognizing those who were fighting relentlessly to keep us living within our means. Not merely given to lip service, dreaming for it without ever acting to achieve it, there were men in both the House and Senate with the courage to carry out the vision of President Coolidge when it came to constructive economy. These men, Representative Madden and Senator Warren, were matched only by Cal’s Budget Bureau Director, General Herbert M. Lord, commended “because he has had the judgment to say yes when the facts warranted and the courage to say no when the facts warranted.” His experience, clarity of mind, and ability made him central to the success of Coolidge’s program year after year just as General Washington was crucial to the triumph of American Independence. As 1928 dawned and some began to question why these meetings kept going, Coolidge anticipated their protests and furnished abundant answer to their objections. The Coolidge program would roar forward into the new year with a clear grasp of what it was there to do and how it benefited the country immeasurably.