“With worms you played more fairly with the trout. You offered him what he wanted most. You bet a worm and he wagered himself. If the trout lost, he usually had the worm, or most of it, not just a mouthful of deception to add bitterness to surrender. Fly-fishing, comparatively, was a cheap fraud in which the victim staked his all against an utterly inedible jigger that looked like something it wasn’t. The trout could not possibly gain anything; he could lose everything on nothing more estimable than vanity. The sole death-bed comfort he possibly could derive was the knowledge that he had been hooked by a purist. It is easy to understand why a politician might come to prefer flies” — Frederick Van de Water, In Defense of Worms and Other Angling Heresies (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1949), pp.71-72.

“…[I]t perhaps adds to the spirit and emphasis of our dissent when we are told that fly-casting for trout is the only style of fishing worthy of cultivation, and that no other method ought to be undertaken by a true fisherman. This is one of the deplorable fishing affectations and pretenses which the sensible rank and file of the fraternity ought openly to expose and repudiate. Our irritation is greatly increased when we recall the fact that every one of these super-refined fly-casting dictators, when he fails to allure trout by his most scientific casts, will chase grasshoppers to the point of profuse perspiration, and turn over logs and stones with feverish anxiety in quest of worms and grubs, if haply he can with these save himself from empty-handedness. Neither his fine theories nor his exclusive faith in fly-casting so develops his self-denying heroism that he will turn his back upon fat and lazy trout that will not rise” — former President Grover Cleveland, “Some Fishing Pretenses and Affectations,” in Fishing and Hunting Sketches (New York: Outing Publishing, 1907), pp.122-123.

When it was discovered that the President used worms rather than flies when he went fishing in the Adirondacks, as he had done all his life, some “professional” fly-casters were appalled. It should be beneath the dignity of the President, they huffed. A few among the press even encouraged the sensationalism with stories recounting this supposed affront to the sport of fishing. Coolidge and his regular fishing partner, Secret Service man Edmund Starling (who introduced Cal to fly-fishing), knew better, as did most of those who practiced the noble sport. It was much ado about nothing for anyone aware of the joy and challenge found along countless streams, rivers and waterways. Bait fishing was the sport at its most fundamental, removed of all pretense or snobbery. It relied not on the sophistication of equipment or the scientific precision of the caster but on the simple gambit that occurs whenever human nature matches wits with fish. Through bait fishing, the challenger swimming at the other end of that line and rod was rewarded not with empty promises or mere guile and deception but with a return for its efforts, should it elude capture. This showed a natural respect for the fish as well as a human’s place in nature. Surrounded in the majesties of the outdoors, it only made common sense for men who lived simply, as Coolidge did, free of ostentation, vanity or the need to impress others, to fish consistently with that manner of life. It lived in step with nature not against it. Just as Frederick Van de Water and Grover Cleveland put it, the fly-caster may look down on bait fishing but when the best cast fails and the fish refuse to fall for the fly, all default to good bait. The simple forthrightness of this truth strips the veneer off a politician’s guarantees just as effectively as a fly-caster’s attitude of superiority over his method.

Mrs. Coolidge, in her Autobiography, recounts three favorite memories of her husband’s fishing experiences, the first of which revealed Mr. Coolidge’s previously untapped fascination with the art and sport. It started the summer of 1926 in the Adirondacks. She writes, “It was here that the President took up the serious business of fishing, and with the success which usually attends his efforts, for we served a fish course at luncheon every day.” Sometimes in search of pike or pickerel, he usually went fifteen miles away in the quest for trout. “Enthusiasm for the sport had so taken hold of him that at the close of the fishing season he was reluctant to give it up. He scanned the New York State fish and game laws and learned that while fishing was not permitted in the county in which we were living after the first of September, it was not prohibited in the adjoining county until Labor Day, a fact which was not known to the guide or to the caretaker of the camp, himself an ardent sportsman.” Here it was beneficial to know the gaming laws better than the experts did.

Her second favorite memory unfolded the next year as they stayed at the Game Lodge in the Black Hills of South Dakota. She narrates, “The President took a second summer course in fishing, which resulted in increasing skill. A kind neighbor gave him the exclusive privilege of fishing in a stream which ran through his farm, and many a delicious trout did he bring home for the family dinner. There was one experienced old fellow living in a certain hole, which he tried to attract with every sort of alluring bait, but the finny creature proved wary until in an unguarded moment, on the last day of fishing, curiosity got the best of him and he rose to investigate a salmon egg sandwiched between two worms, only to find himself impaled upon an ugly hook.”

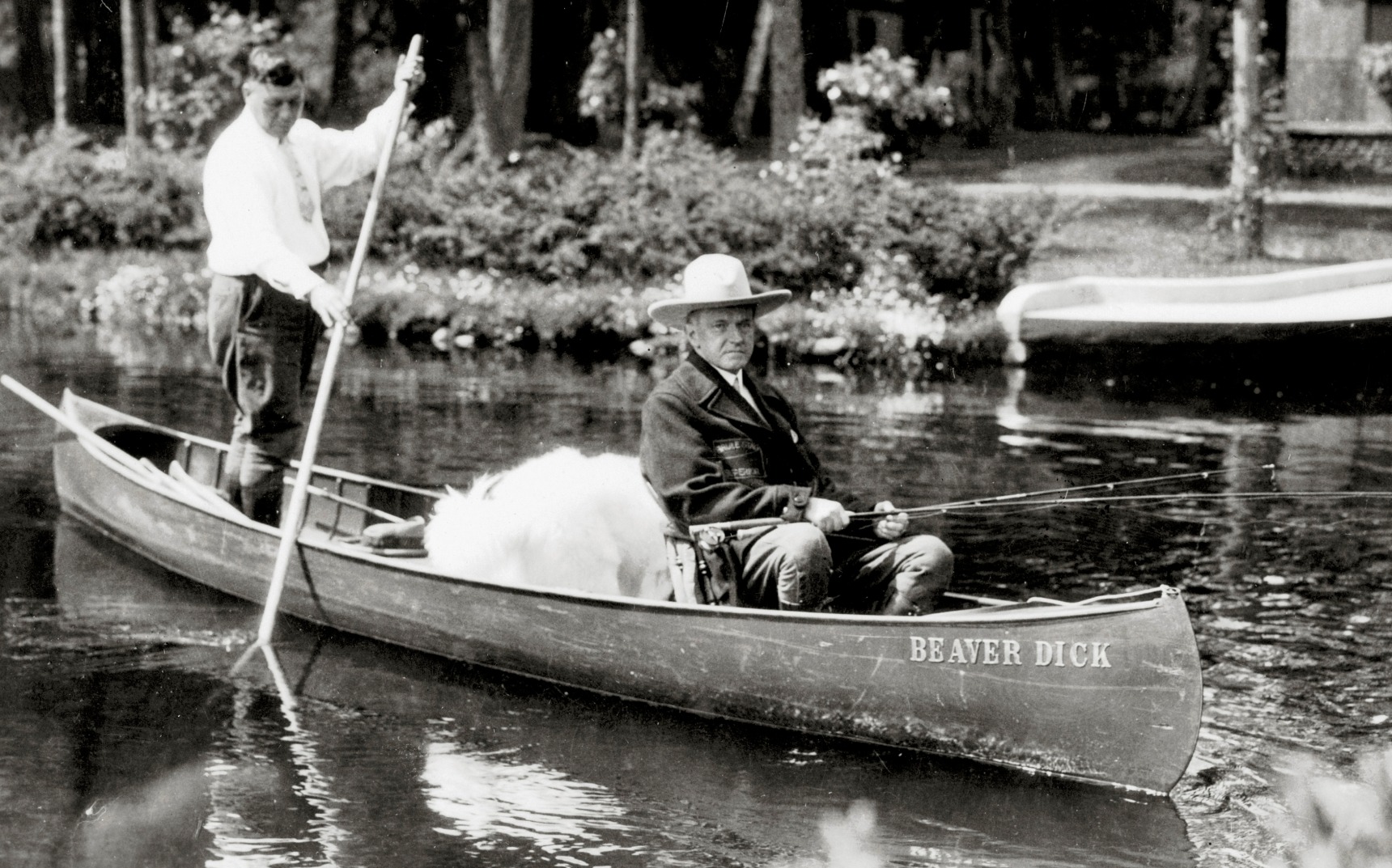

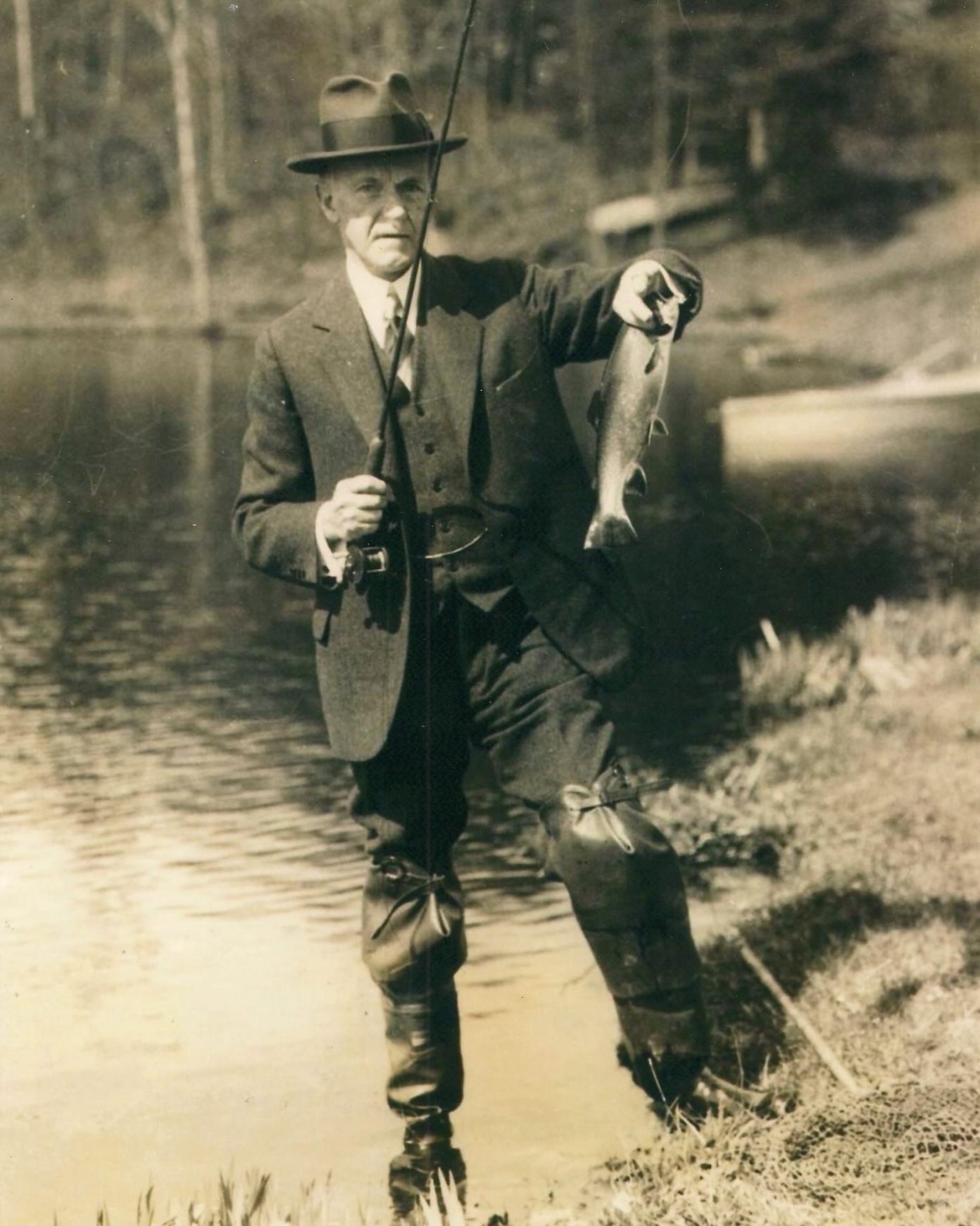

Coolidge held scrupulously to accurate fish stories. He made a point of photographing what he had caught in order to have visual verification. Here he holds his latest catch up for confirmation.

Her third memory came in their last summer before leaving the Presidency, as they stayed on the Brule River in Wisconsin. Their cottage, located on a small island, was accessible from a roughly hewn wooden bridge that spanned the two shores. It was underneath that bridge where President Coolidge met his toughest challenge yet, among “several large trout who were rather tame and looked to us for their daily food consisting of crumbs from the table.” A particular trout, a “very greedy one” (in Grace’s words) was named by the President. He called him ” ‘Danny Deever’ — ‘for,’ said he, ‘I’ll hang him in the morning.’ ” Referencing Kipling’s popular 1890 poem, Coolidge relished not only the play on words but also the dramatic personification of his piscatorial nemesis, as any admirer of literature can appreciate. In the trout’s case, despite repeated efforts to lure him up with “pretty flies” (notice Coolidge was no purist theoretician, using flies and bait as circumstances warranted), Grace kept Danny fed so well that the “hangin’ in the mornin’ ” never took place.

One wonders how many more fish stories might have been told had time and opportunity allowed Mr. Coolidge and his friend Starling to go on that great cross-country fishing expedition they had planned. One thing is sure: Cal would have brought the worms.