“That young chap Coolidge certainly has more stuff on the shelves and outs less in the show-window than any fellow I’ve ever seen” — Northampton shopkeeper on the future President.

We all know someone who, upon learning of new information or undergoing an event important to him or her, immediately dashes off to “share” it on social media, text it to friends, and generally advertise whatever it is, was, or will be, however trivial, to the rest of the known world. Good and fun-loving people otherwise turn what could be an enjoyable time alone (gasp!) or in the company of friends, family, and those actually present, into a communal experience of imposed participation. Not everyone wants to know where your new tattoo is located. The web is not anticipating with whom you had a picture taken tonight. Not everyone is waiting breathlessly for your next cryptic reference to the latest chapter of self-imposed drama in your life. Social media is no less immune to those old-fashioned standards of polite, considerate, and discreet behavior that used to govern all relationships. Life is fraught with difficulty and exciting things happen to us all from time to time but we seem to abhor ever going through any moment of it alone, in the solitude of our God-given individuality! Of course, we all desire to be important — an achievement that seems even more all-consuming these days with the globe a click away. Also, it is not to detract from life-changing occurrences that can now be communicated without ever picking up a telephone. It seems that rather than leaven a balance into one’s perspective, however, all manner of news items become open season to disclose to everyone within range that you know about this or that, you feel such and such concerning it, or you have a comment on something about which you have an opinion, whether it is informed or not.

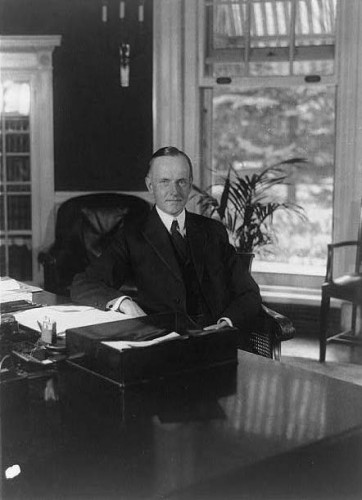

Calvin Coolidge was not this kind of person. He did not display all he was for just anyone to see. He didn’t wear his heart on his shirtsleeves either. This hardly means, as some have interpreted his silence to mean, that Cal simply buried his head in a pillow, closed his eyes and slept through life, oblivious to what was going on in his world. He knew a great deal more than he admitted. He observed everything and little could escape his notice, however small or insignificant it might be to others. He had a way of discovering who people were – what made them tick – and what was going on in their lives, without all the effort of lengthy conversations. When something exciting, like the arrival of Mrs. Longworth’s new baby hit the news and Mrs. Coolidge learned of it, she discovered that he not only already knew, he had projected the due date from listening to others. When people sought to know how Cal had enjoyed a certain theatrical performance, after he and Mrs. Coolidge attended one in Boston, they could be left wondering for quite some time until he would acknowledge that he had been back to see it several times since.

One of his teachers when Calvin was little, Miss C. Ellen Dunbar, describes this incredible aptitude Coolidge had for both a discretion and, at the same time, a complete awareness of what was transpiring around him. She helps put this quality of his personality in perspective, recalling,

“I taught Cal when he was eight years old. He looked as sedate then as he does today…If you had called him ‘Judge’ when he was a little boy it would have fitted him well. He had a deeply thoughtful mind almost from babyhood. I knew his parents before he was born. Those who meet Cal today speak of his apparent aloofness. He was the same with his schoolmates.

“I never knew Calvin to get into mischief. He didn’t play much with the other boys, not because there was any unfriendliness, but what appealed to them didn’t appeal to him. Calvin was trained not to bring his troubles to his mother. He kept them to himself. His mother was sick and mustn’t be worried. John Coolidge was wonderful to his women. Calvin’s sister died in her father’s arms, of what would be called appendicitis today.

“Calvin gets a lot of his characteristics from his grandmother, Almeda Coolidge. As school teacher I used to board around. I lived for a long time with Calvin’s parents and also with his grandmother. Almeda Brewer Coolidge was a widow when I knew her and had a wonderfully friendly personality. She had the greatest way of finding out all you knew; Cal’s that way, too. I wasn’t in Almeda’s house three days before she had me turned inside out–knew everything I knew. Cal’s like her that way. And I never heard Almeda Coolidge criticise her neighbors…

“With him ‘to be a man’ was the thing, not to be CALLED a man. When he was a little boy he was Calvin Coolidge of today in miniature, except that now his mouth shuts down a little tighter. Calvin Coolidge can’t dodge his heredity or his long years of training. He wouldn’t lie to save himself from the gallows” (Horace Green, The Life of Calvin Coolidge, New York: Duffield & Company, 1924, pp.18-19).

He was not given to effusive reaction, it was simply his nature. This did not mean he did not care. A calm restraint and disciplined discretion defined all of his life, with friends and strangers alike. His reputedly expressionless exterior concealed a genuinely caring and observant man. Secrets, however great, were always safe with him. If anything, it illustrated his respect for people that he would not violate a confidence – even when one had not been expected. It confirmed his regard that each person has sovereign right to do what they wish with what is their own property, including one’s experiences. Not only is each individual to be master of his or her own speech but personal information was no less sacrosanct to him. Some folks seem all too eager to abdicate that sovereign power and distribute it in ways that prove harmful to themselves and to others, actions or words that can never be undone or reversed. Freely giving away this kind of control over one’s life, mind, and person was simply undisciplined, illustrative of bad judgment, and foisted an absence of thoughtfulness toward others in public. It was not walking in love (i.e., the Golden Rule) to which Calvin appealed time and again.

This is not to say we become “silent as the grave” or take up monastic living from henceforth in all our dealings to somehow realize what we mistake Cal to be saying. It is an irony noted by Coolidge biographer Claude M. Fuess that Cal did not like to be alone yet he did not need the interaction that is usually thought to be inseparable from it (The Man from Vermont p.470). He had that way of learning what a person knew without divulging his own thoughts and feelings, without leading a life lived in what he would call, “the Show Window,” where everything in our makeup is on display out front for all passersby to see. Cal did not live that way yet he still learned who people were, sometimes, better than they knew themselves. He made good use of the silence.

Coolidge understood that there is a time to speak and a time to be silent. Our right to speak and be heard is no more absolute than the rights of others not to listen or be compelled to take part whatever we want to share. This is but a reminder from wise Mr. Coolidge that respect never be lost in the way we relate to each other and that discretion for how others are “hearing” us is just as important. Let our speech give grace to those who hear and our ability to listen be improved in the quiet times. Being alone in our thoughts is not always an intolerable prison from which to escape, it can be a refuge and comfort, an occasion to rally strength and prepare for doing better by others than we have done. We will find that much of what we feel compelled to say, especially in the heat of the moment, does not improve upon the silence and we would avoid a great deal of trouble by talking less. This may be obvious to many, but thank you, Mr. Coolidge, for reminding us of its importance.