Last December when we examined the First Annual Message delivered by President Calvin Coolidge, December 6, 1923, we observed that this speech shattered the perception that Cal had nothing to say, little to offer, and even less to do. A careful look at this and the Second Annual Message, delivered in December 1924, contradict this perception. Writing at the close of his administration, Coolidge would actually make the claim that most of what he had proposed in that first address had become law by the time he would leave Washington. How did such a historically-miscast “do-nothing” get so much accomplished? We will take a look at each of his proposals in brief as they reveal a Calvin Coolidge that simply has not been allowed out in public these days because it fails to fit the caricature or desired interpretation at a given time.

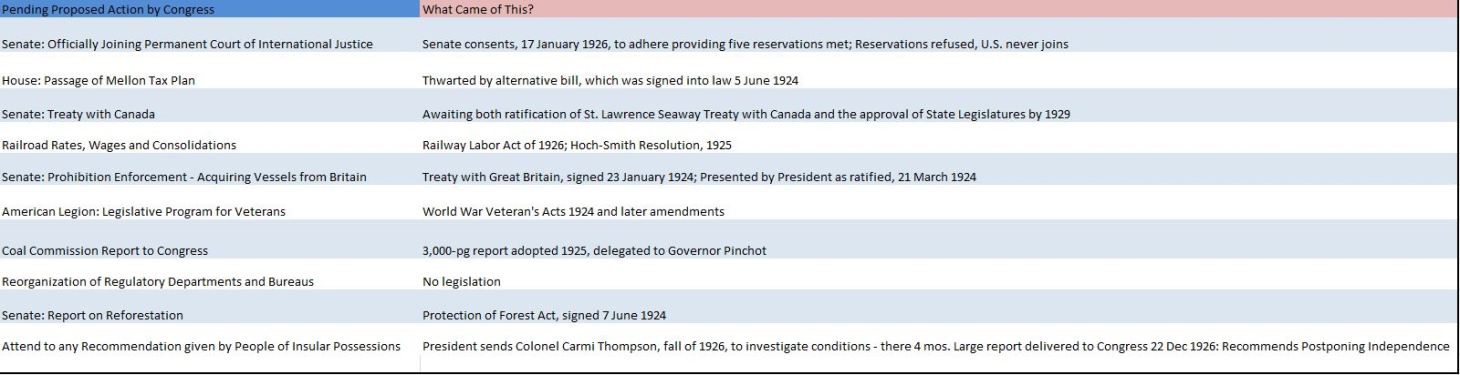

First, however, here are the issues the President observes were either pending before Congress in one form or another:

Residing in the Coolidge Collection at Forbes Library in Northampton, Massachusetts, is this surprising manuscript among his papers, entitled, “Recommendations 1923 Message and Actions Taken.” In it, Coolidge has kept track of each of his proposals but also what happened legislatively to them by the end of his administration. The very existence of this record defies the impression that Cal sat back, slept through his terms of office, and cared little or nothing about what was going on and what needed doing. It is especially instructive that he continued to keep tabs on the developments from his Second Annual Message delivered the December after Calvin Jr.’s death, when (as some has persistently claimed) that he checked out for good and rode out the rest of his time. Of course, it must be noted that many of these proposals had their inception under President Harding’s administration, but it is to Coolidge’s greater credit that these measures were adopted at all (rather than simply dropped by the new President), at times even shepherded to completion, by Cal’s diligent, if also steady and often unseen, pressure. Many thanks go to Mrs. Julie Bartlett Nelson, archivist at Forbes, for her kind assistant in securing a copy of this manuscript for our research.

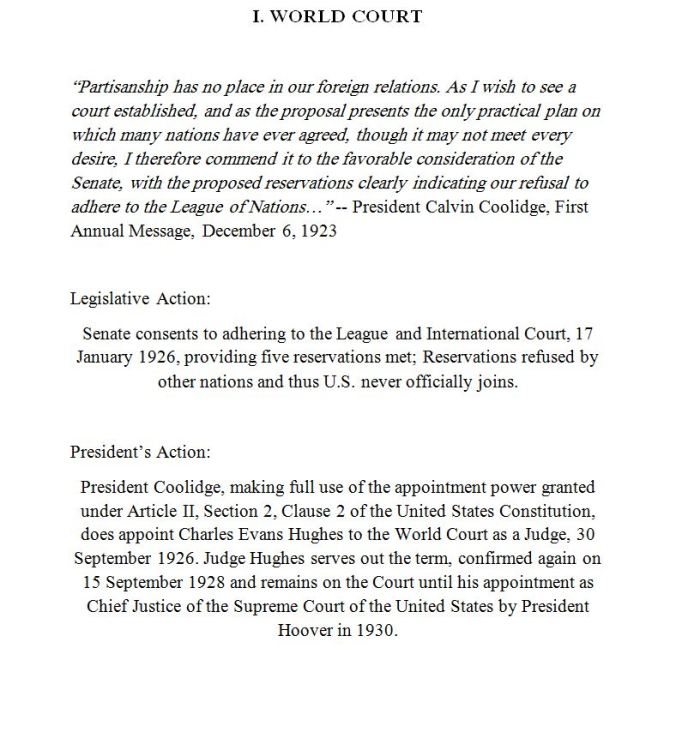

So, let’s begin. While President Coolidge, mistakenly dismissed as too provincial to lead policy abroad, delved right into foreign affairs at the outset of his First Annual Message, he displays both a good grasp on affairs overseas and surprised many for his clarity of thought when it came to the question of what to do about the World Court and the League of Nations. In the manuscript, he begins with what at the time was a very murky issue, fraught with political peril. It had doomed President Wilson and intimidated Harding, what would Coolidge do?

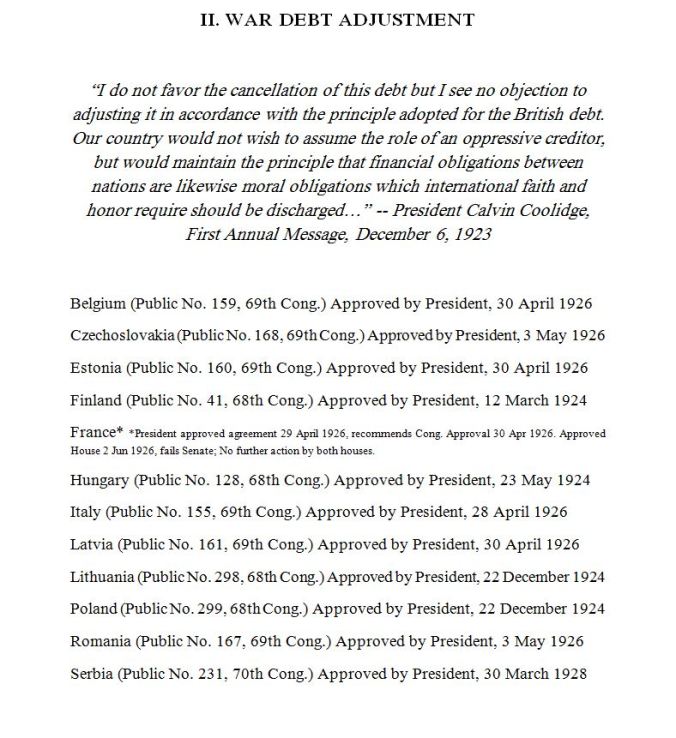

Fittingly, second in Coolidge’s list is the settling of World War I debts owed to the United States, despite it appearing fourth in his actual speech:

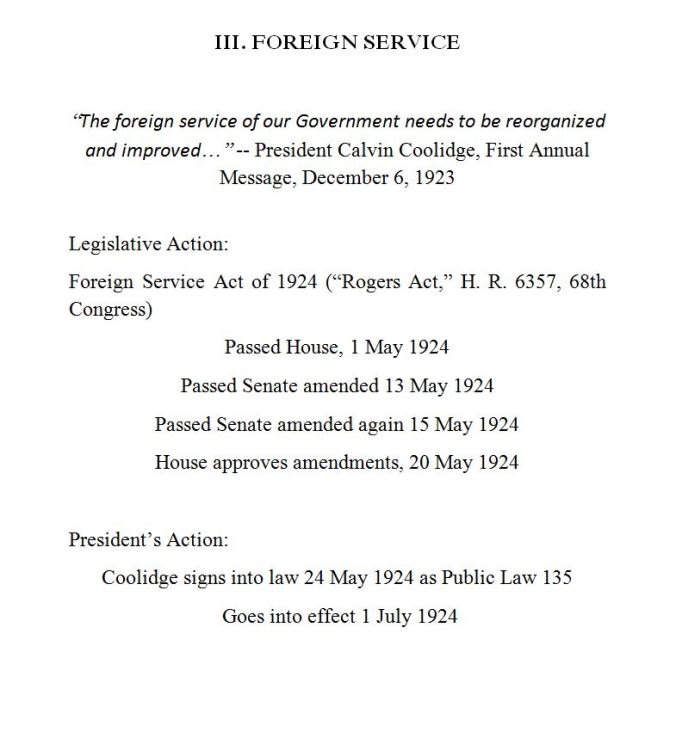

Next is President Coolidge’s proposal to reorganize and improve the Foreign Service:

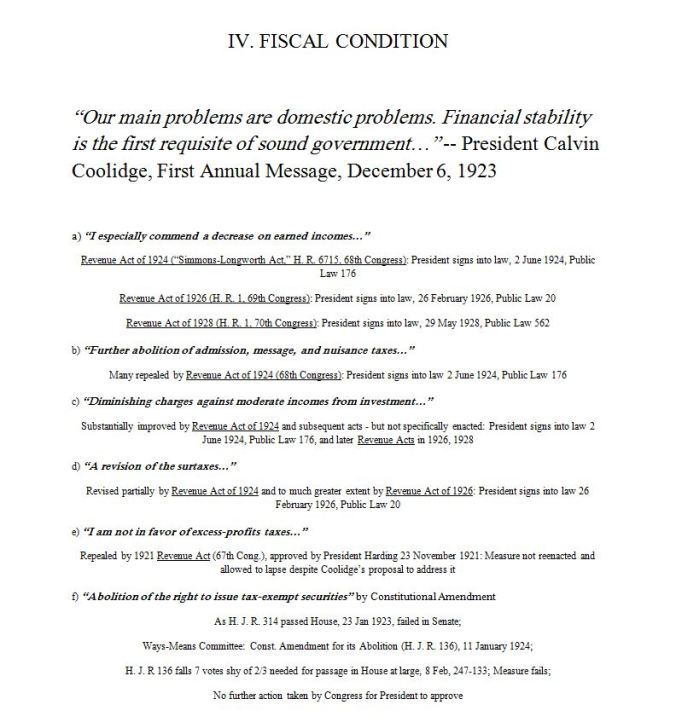

Fourth in his listing is are the Fiscal Conditions of the country, with six proposals for action:

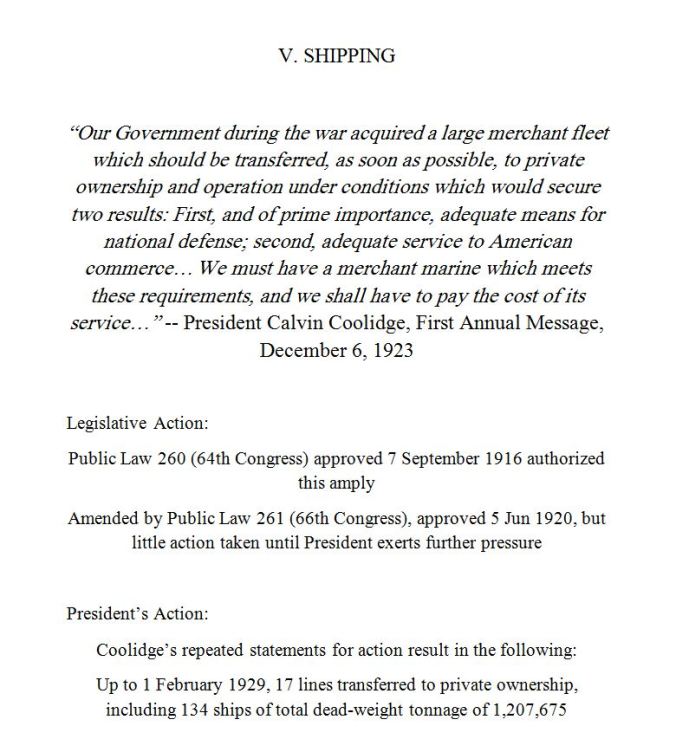

Shipping is featured fifth in this manuscript, while it falls ninth in his First Annual Message. It is noteworthy that the Merchant Marine Act of 1928 (popularly known as “Jones-White”) attempted to serve Coolidge’s twin goals of adequate defense and commerce yet after a long, difficult fight over the expense of the legislation, Coolidge signed a significantly less costly version on 22 May 1928. Interestingly, it is noticeably absent from his list of “Recommendations” held at Forbes Library.

:

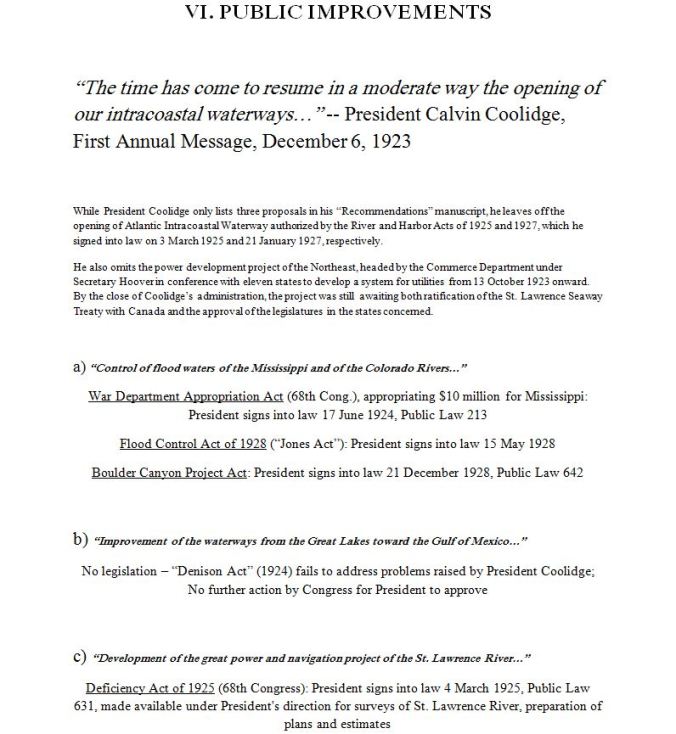

Public Improvements are enumerated next in the Coolidge manuscript, mirroring their placement in the First Annual Message:

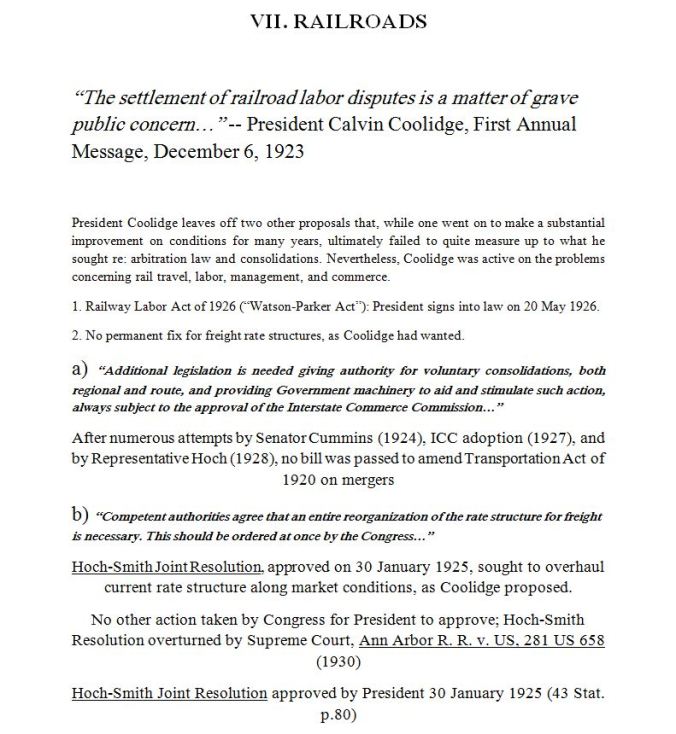

One of Coolidge’s lifelong interests – the Railroads – comes next in the lineup:

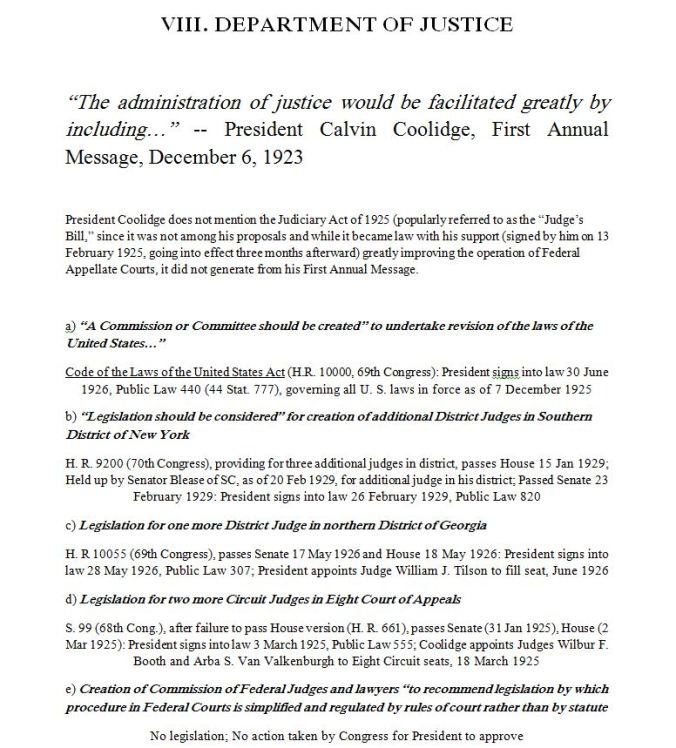

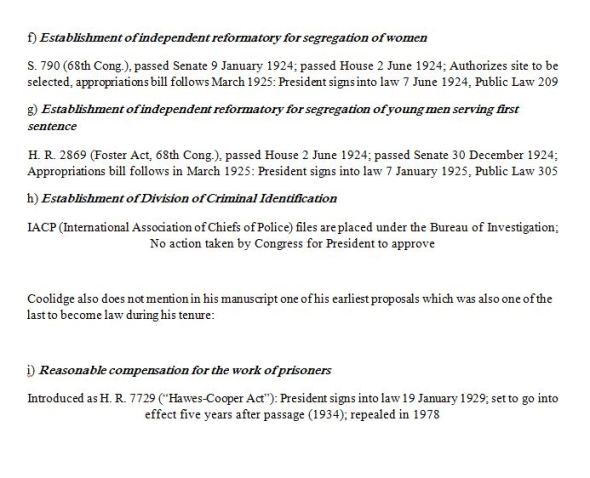

Eighth in our manuscript are Coolidge’s proposals for the Department of Justice:

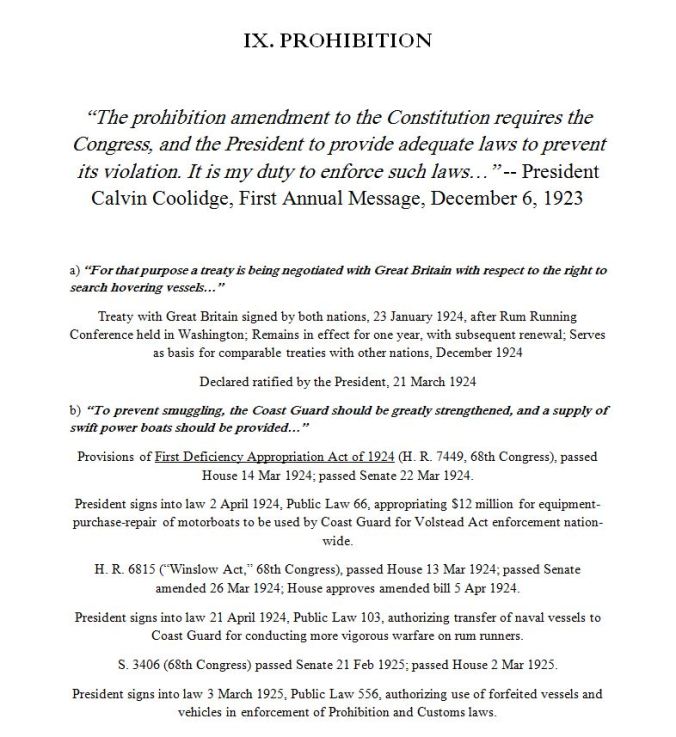

The unpopular and politically “mine-laden” issue of Prohibition comes next. His personal feelings aside, he had taken an oath to uphold the Constitution and the laws, including even the bad ones. Coolidge proposed the following:

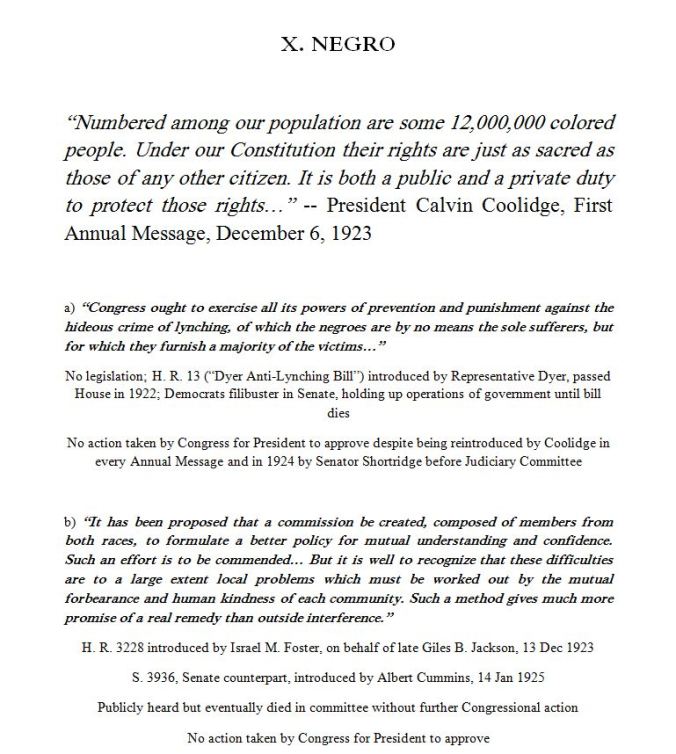

Next in the broad range of subjects Coolidge includes in his manuscript tracking what came out of his First Annual Message proposals is this perhaps even more controversial issue, the Negro. It is important to note here that not only did President Coolidge make a point of reminding Congress every year he was in office of the situation concerning black Americans but also of his two principal recommendations for the betterment of the whole country, regardless of color. The sooner the nation moved forward together, judging people on the basis of character, the better conditions would be. It is also insightful that while the lynching law never passed, lynching went down steadily throughout the Coolidge administration from its appallingly high numbers in the decades preceding him. This was hardly coincidental. It is also revealing that on more than one occasion Coolidge writes, “No legislation,” when, in fact, legislation had been drafted, even passed one chamber of Congress, but because good intentions did not stand in for substantive action in Coolidge’s estimation, without concrete results he could honestly declare nothing came of the matter.

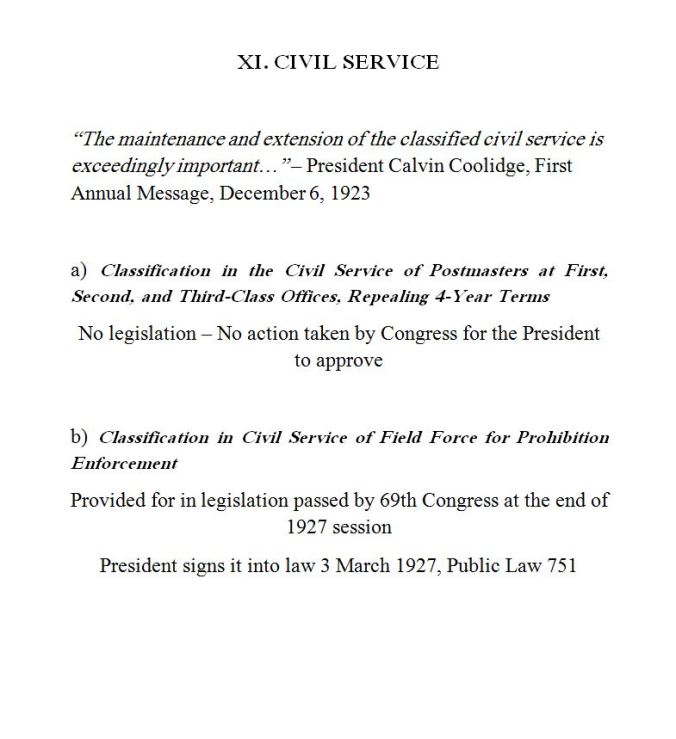

Civil Service recommendations follow:

The long-time neglect of sound public buildings is met by Coolidge’s next proposal. It is a reminder that Cal did not always say “no” to any expenditure, there were legitimate needs to spend sometimes:

A series of regulatory proposals are put forward by President Coolidge next. Among them are some of his best-known legislative successes, foremost of which are the Air Commerce Act of 1926 and Radio Act of 1927. To Coolidge, there there was both a time to save and a time to spend. There was a time to regulate and legislate just as here was a time to refrain from legislating:

Few items have engendered as much misunderstood, even misinformed, emotional responses as military spending these days. In Coolidge’s time, before the growth of a vast Department of Defense bureaucracy, differentiating between an adequate defense and an unnecessary expenditure was easier to accomplish. Coolidge understood what so many fail to grasp now that not all military spending is beneficial nor essential to national defense. Defense spending meant those expenditures necessary for actual defense materials.

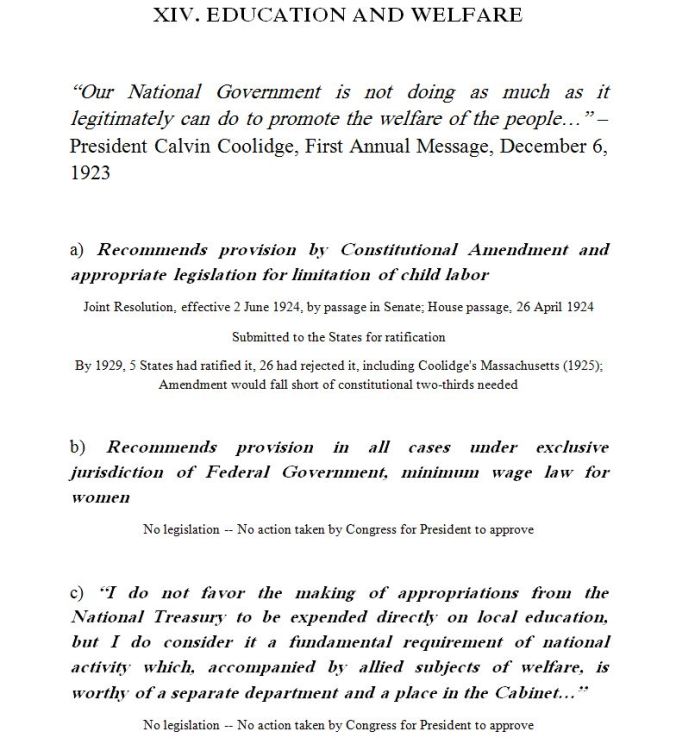

Proposals concerning education and public welfare are presented next:

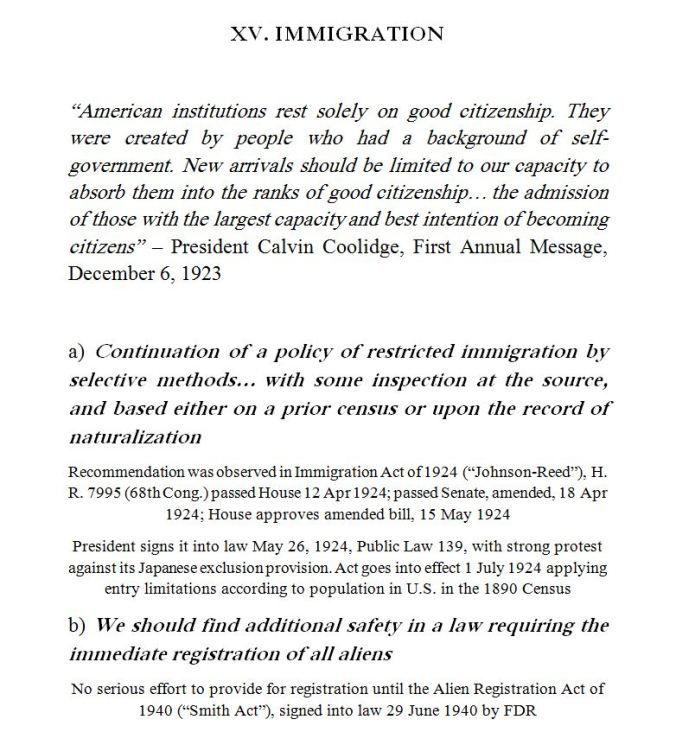

Coolidge would continue a policy of limitation when it came to immigration, believing that the Constitution does legitimately authorize Congress to make and the President to approve laws of entry and citizenship. He also knew from the practical experience of years in immigrant-rich Massachusetts that removing all restrictions – aside from the criminal and dangerous – harmed those, born and naturalized, already here by taking away opportunity from those who had become established as citizens, presenting those most recently arrived with the lesson that rewards precede responsibilities, the preferential treatment of simply arriving rather than the honor of work and earned citizenship. Coolidge recommends:

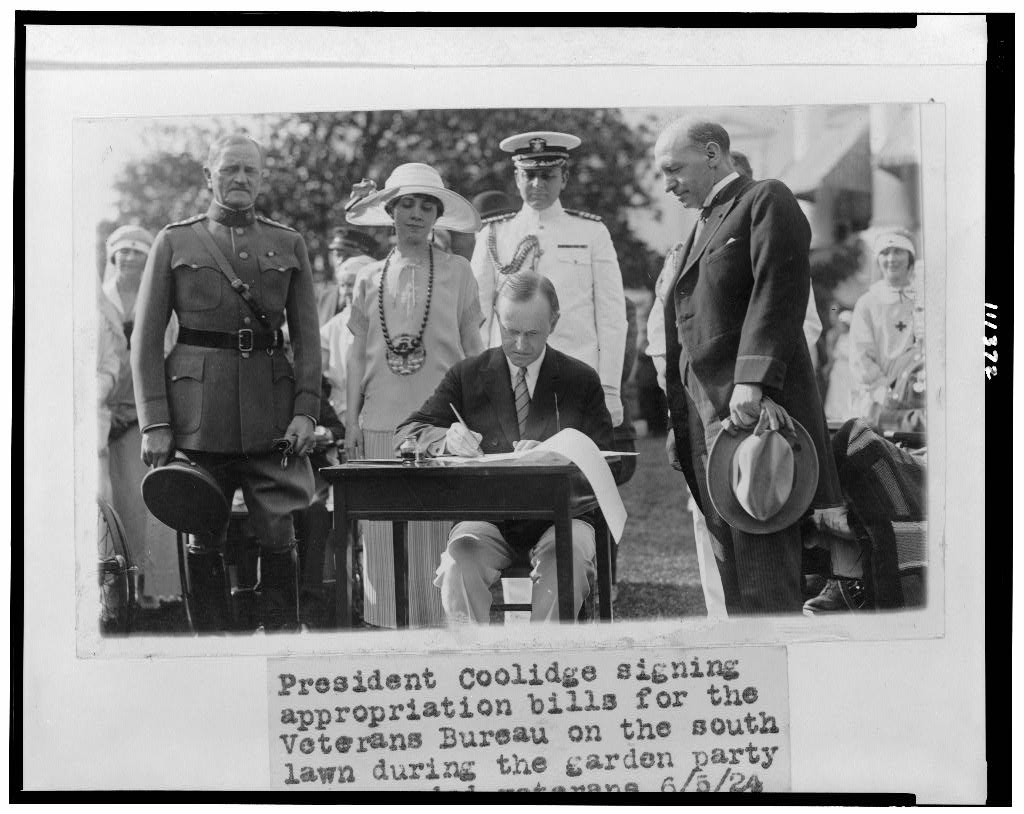

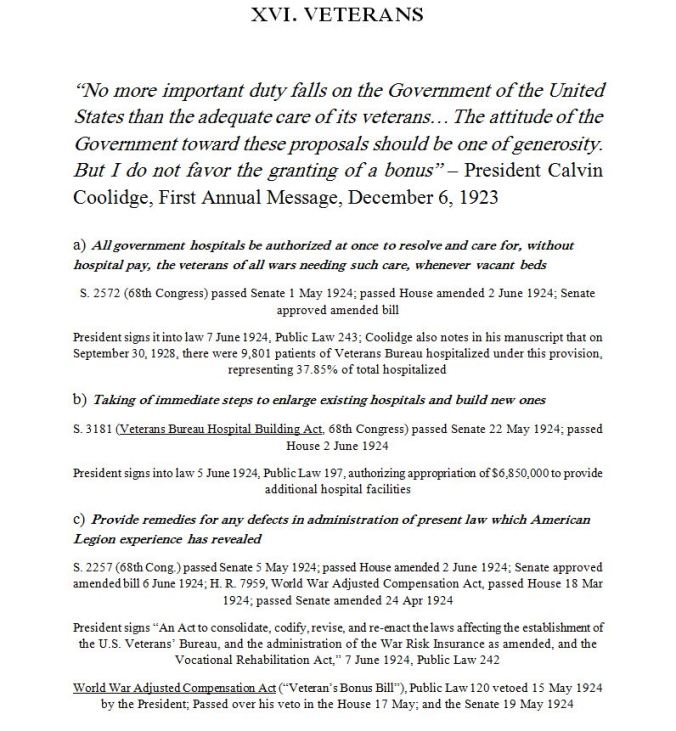

Veteran’s benefits are as accepted and expected today, if not more so, than any of the other welfare programs that have become part of society. Not so in Coolidge’s day. There certainly was one of the strongest legislative lobbies for veterans in existence but the President was not afraid to make enemies when it came to government picking winners and losers, preferring some and ignoring others. Calvin Coolidge held a different view. Not only was a Veteran’s Bonus playing favorites with a specific demographic at the expense of the whole people, it was presuming to place a monetary value on their service, something Cal regarded as beyond material reward. It demeaned their sacrifice not honored it. This is why he vetoed the Bonus Bill but also why he gives these three alternatives to best help our veterans:

President Coolidge then turns to address potential trouble in one of America’s crucial industries, Coal:

Reorganization was Coolidge’s most unfortunately unsuccessful proposals, directed as it was against the creeping bureaucracy that had accumulated in his day. It was something he had already tackled at the state level, reorganizing twenty departments out of the one hundred and twenty that dotted Beacon Hill when he took office as Governor of Massachusetts. Anyone who had watched Coolidge knew he could do it again, if given the chance, even at the Federal level. The President bravely “went there,” where few are bold enough ever to venture. Here stands his recommendation and its frustrating reply by Congress, for the ages:

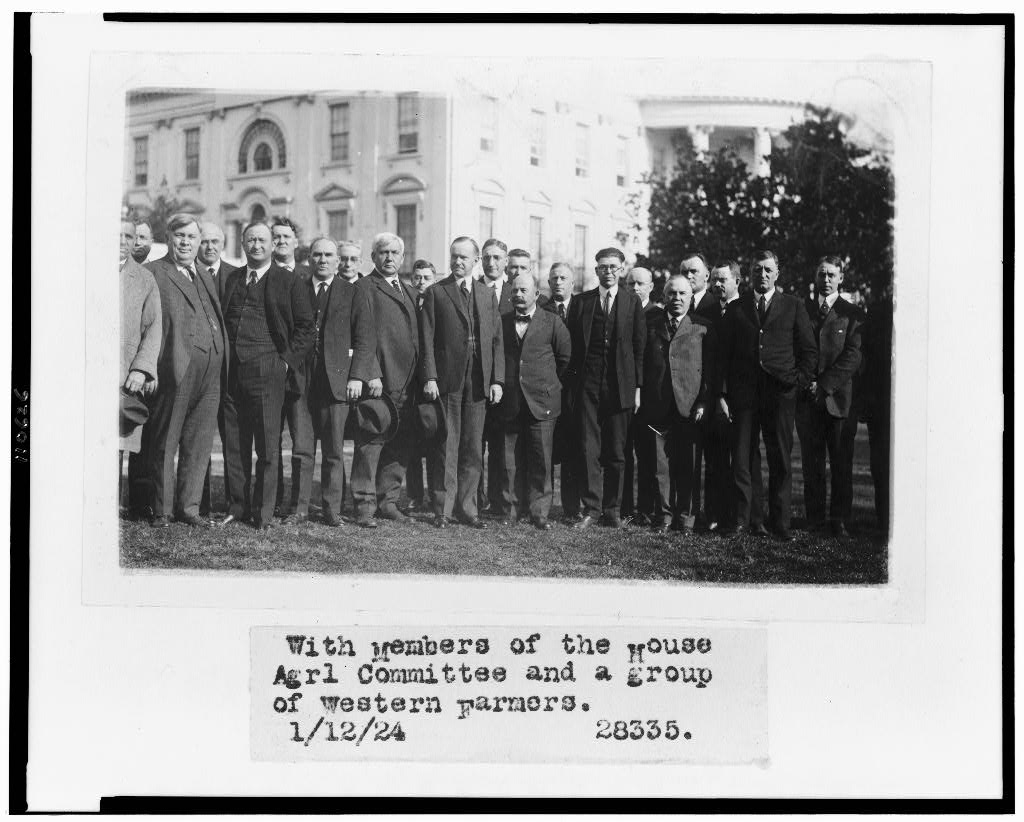

Coolidge then directs his focus to agriculture, a recurring source of confrontation between the White House and what was known as the Farm Bloc, the Representatives and Senators of various agricultural states. Coming from one of the most rural areas of the country, Vermont, Coolidge appreciated better than most what it meant to struggle with the land but that also meant he knew that government ownership of any part of the process neither would nor could solve the farmer’s plight. His recommendations met with skepticism, even hostility, from the Farm Bloc, which wanted guaranteed prosperity delivered courtesy of Washington, D. C. There were things Government could do to encourage better circumstances, but the power to improve rested where it always will: with the farmer directly. The President presents a different take on the situation:

Another nagging problem that seemed to refuse resolution during the Coolidge years was what to do about Muscle Shoals, the water-power plant seized under President Wilson to produce munitions. Again, the Farm Bloc would stand in the way of selling the property and getting government out of its operation, as we see below:

The final two issues President Coolidge includes in his unofficial record of 1923 legislative proposals and their outcomes concern Reclamation and Highways and Forests:

Coolidge’s manuscript does not end there, however, it goes on to enumerate the policies he recommends in the Second Annual Message and what was done about them during his five and a half years in office. For our purposes here, however, it seems obvious from looking at his First Annual Message alone that President Calvin Coolidge was anything but a “do-nothing,” with no agenda, no direction, no focus of his own. The contents of this document refute that oft-repeated perception. He was anything but inactive, continuing to keep this kind of legislative diary all the way to February of 1929.

These legislative items are only a partial glimpse into the thorough care Coolidge poured into his Presidential work. It says nothing of the hundreds of laboriously considered appointments, his judicial selections, his vetoes, his executive orders, his carefully crafted speeches (all of which he wrote himself), his diligent attention to every correspondent’s inquiry, need, and concern, and the countless number of executive decisions that have been relegated to the footnotes of history not because the times were insignificant or the President’s leadership lacked something but because he usually reached the right conclusion, the one that diffused the situation, brought resolution and met his obligations to best serve the people.

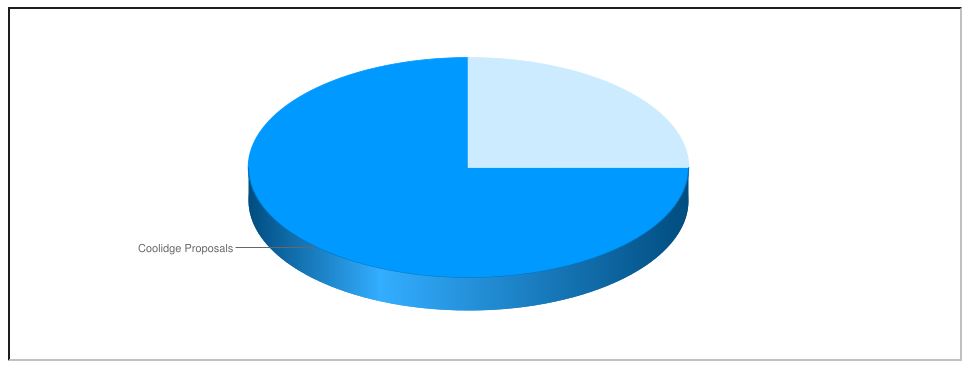

This simple pie chart illustrates the success rate of his proposals: 74.9% of them becoming law, while 25.1% were either not acted upon at all or simply fell short of full passage in Congress.

As this document should reveal, Coolidge was anything but inactive during his six years in office. Though he had a gift for delegation and a practiced hand for refraining after years of Presidents rushing in to handle an issue, Coolidge still did when the time came to do what needed doing. His sixty-six recommendations – from his First Annual Message alone – grouped into twenty-three categories, would be combined with numerous others pushed in his subsequent speeches. There was no sitting back and waiting for others to present the vision for his administration’s policy, he would do it himself. Moreover, while a mere sixteen of his recommendations met with no action on the part of Congress, the vast majority produced some result, just as Cal would claim in his Autobiography.

Moreover, his greatest legislative achievements, measures he actively fought to secure, such as the Revenue Acts, Air Commerce, Radio Act, Revision of the United States Code, and War Debt Readjustments speak to a much more actively involved Coolidge than is thought. Even his failures to secure the Federal Anti-Lynching Law, the Commission on Race Relations or the Reorganization of Government Departments reveal an engaged Chief Executive who, even out of his setbacks, saw lynching and racial tensions decrease as well as government do more with less. Coolidge, a “do-nothing” President? Think again.

Reblogged this on The Importance of the Obvious and commented:

In difficult times, we very naturally seek out those who are often underrated and forgotten examples of courage and strength to steel ourselves for what needs to be done. When substantive heroes are wanted, we quickly find leaders like Calvin Coolidge who seem to be prepared for the occasion. Just when the times need most the qualities and perspective he possessed, an awareness and rediscovery of him is steadily and deservedly occurring. Here, contrary to the myth circulated by friends and foes alike, is a glimpse at a very productive and even busy President, who did more with less than we often realize. Even after the devastating loss of his youngest son early in his Presidency, he seemed to hunker down and work even harder not slackening his sense of duty but intensifying his efforts to serve the whole nation. His rediscovery could not come at a better time.