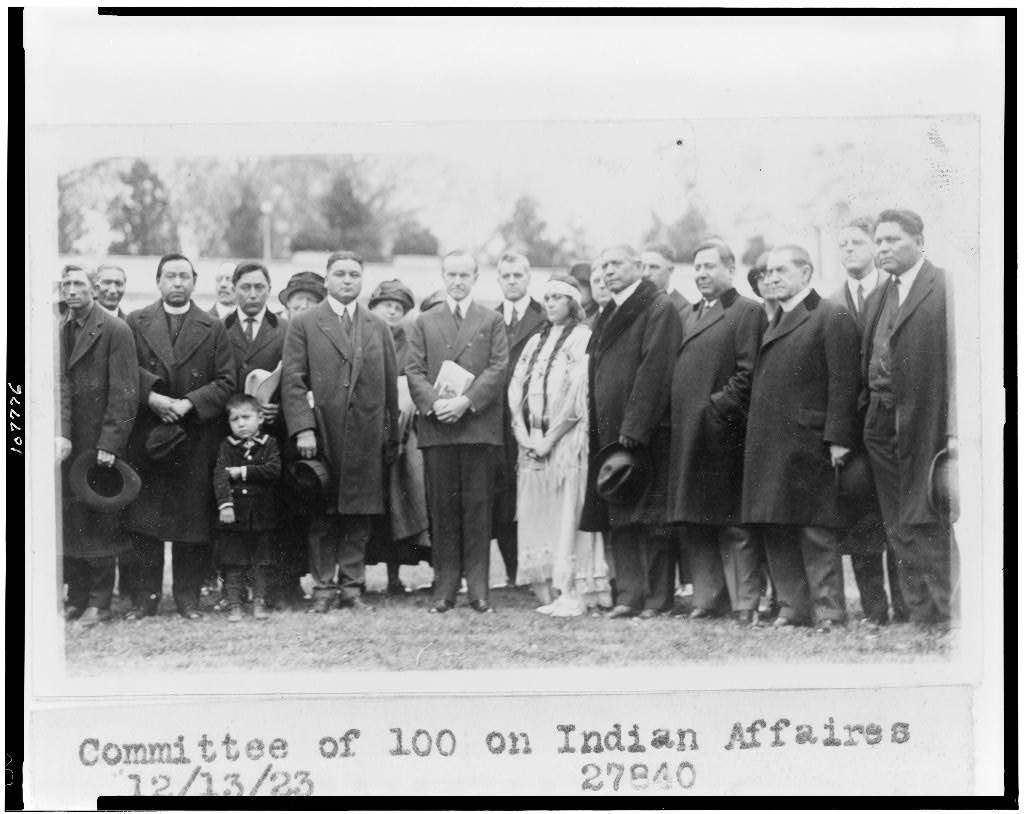

In the months leading up to newly inaugurated President Coolidge’s first Annual Message in December 1923, he invested an enormous quantity of time seeking out advice, input, and counsel from a very broad range of sources. This was not because he needed an agenda, sought to be told what to do, or lacked his own confident sense of himself and what he believed. While many he would summon to the White House left perplexed at what usually constituted a reticent reception and visit devoid of guarantees or enthusiastic assurances that action would be taken, they failed to appreciate what Cal was actually doing. He was exercising the discipline and strenuous effort of good listening. This was no less the case when the Committee of One Hundred, appointed by Coolidge, presented their findings to the President on the conditions of American Indians a week after his Message.

The status of tribe after tribe subjected to government paternalism through the reservation system of decades standing and the land allotment scheme under the Dawes Act of 1887 had been issues either skirted or punted altogether by one administration after another for far too many years. The report of this Committee of One Hundred would prove to be the start of a task that would span all of Coolidge’s tenure to overturn years of accumulated failure in government policy.

It is to the credit of President Coolidge that the buck finally stopped with him. The grave inadequacies of government involvement which had kept these peoples from even the basic advantages of American citizenship would be ended only after a harsh analysis of the facts, however unpopular, had been undertaken. It would finally lay bare the reality that must lead to genuine changes for the better. It is significant that this finally happened under Coolidge’s leadership. It remains one of his finest accomplishments for civil rights. Three important actions by Coolidge merit brief consideration as we mark the day, ninety-one years ago, that one of these actions, his signing of the Indian Citizenship Act, took place.

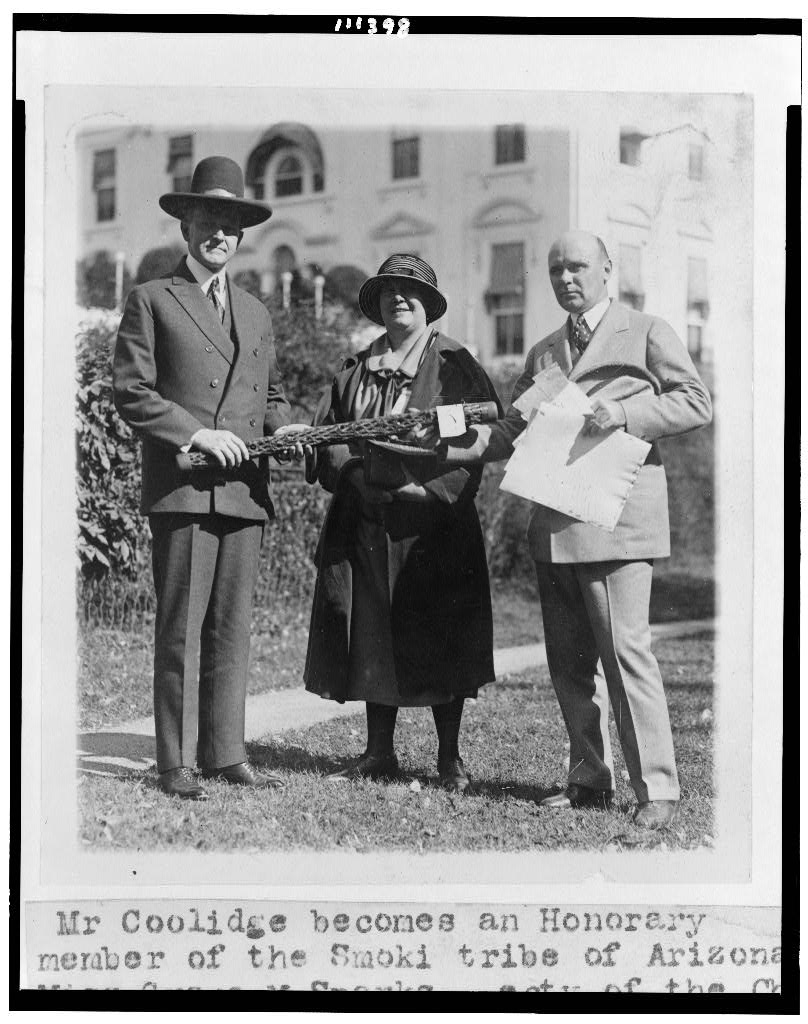

1. He took the time to meet with the tribes and later to be inducted into their membership. From the Navajo and Apache to the Sioux, Cherokee and Osage, Cal met with representatives from all of them and more. He accepted their gestures of regard and returned his gratitude for a proud and brave people. He appointed the Committee of One Hundred, meeting in mid-December 1923, to begin the process of correcting the deeply entrenched mistakes of a flawed system. Once asked about his frequent joining of Indian communities, Cal replied, “Just because I belong to one tribe is no reason why I shouldn’t belong to another.” When Coolidge was named part of the Sioux at Fort Yates in South Dakota in the summer of 1927, a chieftain turned to Calvin and said, “They tell us you are the thirtieth President of this great country, but to us you are our first President.”

This was not calculated courtesy, or political opportunism, he had earned a respectful place among these men and women because he first respected them as individuals worthy of the fullest citizenship, as brethren not subjects or even foreign savages. They had sacrificed and died beside the rest of us, Coolidge asserted, in the Great War. Did not that alone warrant their full recognition as fellow heirs in all the blessings and responsibilities America made possible? He would return to the West after leaving the White House — when no possible political ambitions were even remotely sought — and dedicated the dam which bore his name, smoked a ceremonial pipe of peace with the local chief and ate together with the Americans of all backgrounds who lived and worked there.

2. He signed the Indian Citizenship Act, June 2, 1924. By some calculations this one measure granted citizenship to more than 125,000 Indians from a population of 300,000. It did not create standards sure to exclude the lowly or reinforce a sense of class under the new law. Citizenship came to the illiterate just as equally as to those who could read and write. The arrangements for property, both tribal and personal, were not impacted at all by the law and it is significant that as early as two years later, the New York Times could report the progress of voluntary assimilation: twenty tribes out of 371 chose to remain in their ancestral tepees while the rest had willingly joined the mainstream of American society. Coolidge knew this was only the beginning but it had to begin somewhere. Closing his message to seven thousand Sioux, he set the scene of an instance at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, “A group of old Indian warriors…arranged themselves around the tomb, while one, acting for the whole Indian people, laid upon the bier his war bonnet.” Coolidge drew the lesson, this was “not an idle gesture…It symbolized the outstanding fact that the red men and their neighbors had been brought together as one people and that never again would there be hostility between the two races. As one of those old warriors said: Who knows but that this Unknown Soldier was an Indian boy?” (Johnson, Why Coolidge Matters 193-194).

3. He commissioned the Meriam Report that resulted in the most careful study yet undertaken of overall policy direction, health, education, economics, family and social life, migration, legal issues, and missionary work among the Indians. To understand how important this was, a study this thorough had not been done since 1850 and the most determined effort to restore and correct the Indian problem had not been seriously waged since President Grant in 1871. Equally significant is the fact that Coolidge did not turn to the bureaucrats of Indian Affairs to accomplish a self-policing examination. He had his Secretary of Interior task a group of researchers independent of the government – members of the Institute for Government Research, what would later become the Brookings Institution – each assigned to their established specialty. The men and women of the project, working autonomously, visited 95 reservations in 23 states, interviewed hundreds of individuals, and spent seven months in the field gathering a body of data that would produce the necessary changes to the law in five, short years. Their findings, published in 847 pages as the Meriam Report (named for the team’s director, Lewis Meriam), were presented on February 21, 1928. It had the effect of an artillery shell in a tightly packed trench. Without resort to hyperbole, the Report furnished the solid reasons that policy needed to change. As with any government program, however, the wheels moved slower than Cal would have liked under his successor, Herbert Hoover. Still, it is a testament to Coolidge that any of these efforts took place at all, let alone that the opening volleys he authorized to end the old system would at last bear fruit the year following his death in 1934.

On this day, we mark not only the citizenship of the American Indian but also Calvin Coolidge’s actions to bring the races together, to restore a peace long needed, and live an example of respect for every individual on the basis of character and sacrifice instead of color and class. We are all Americans now and in that, we should not only remain humbled but proud of our shared inheritance.

(Note to the reader: The above caption, entered by earlier archivists at the Library of Congress and perhaps by news correspondents beforehand are mistaken about the Smoki tribe, which was not actually a tribe at all, but a group of white Americans appropriating some of the cultural elements and traditions of the Hopi, see here. Thanks to one of our attentive readers for making this distinction).

I appreciate this piece. There’s lot’s of Great info. However, there is one point that should be corrected. The Smoki (mentioned in the text concerning tribal memberships, and below a photo of Coolidge wearing a Smoki Stetson) was not a Native American tribe. It was a group of White business people who performed ceremonial dances for money. Many tribes, particularly the Hopi, objected to what they viewed as sacrilegious displays.

Thank you very much for clarifying this point. The article has been corrected to reflect this important distinction. Thanks again for visiting, reading, and contributing!