When the Business Organization of the Government met for the fifteenth time on June 11, 1928, President Coolidge was less than nine months away from completing his term. He had close to five years at a task no other modern Chief Executive has come close to realizing: a Federal administration that spent an average $1 billion less than it took in each year; A balanced budget every year for six years by 1929, all the while reducing taxes four times, paying down nearly a third of the nation’s debt and passing a host of other legislative achievements from the Air Commerce Act, the Radio Act, the privatization of the Merchant Marine and the Flood Control bill among several more. There was much to be proud of given all that had happened and would continue to unfold in the next year. Coolidge would skillfully navigate both a Cruiser bill and what would become the Kellogg Treaty through both houses of Congress and leave the nation better than he found it in 1923. Coolidge, however, did not slacken his pace or ease off his pressure, as some Presidents do when nearing the end of their tenures. He hunkered down. There was still more to do.

He reminded the Cabinet heads, the department staff, and the bureau chiefs that they were not (and had not) been engaged in a work that served themselves, it was so conducted as to promote the welfare of all the people. This was so in good times just as much as in bad times. In boom or bust, there was an obligation that ran both ways: just as these officers were beholden to the people for their administration so the people were obliged to support their government “for its own sake.” That support in the paying of taxes and participation in the process did not hinge upon the merits of the officeholder any more than it loosed the constraints on government to squander the substance earned by the all the people.

Coolidge’s endeavor was managing the finances of the nation in such a way that the maximum benefit is “secured…to the people.” The hundreds gathered at Continental Hall that day were not rigging the system to benefit themselves or their friends. The results of their work were to accrue to those they served, the folks all across the country who had worked hard to provide for their own as well as sustain the proper functions of government. What was being done each year through these strict efforts to keep within our national means was being “felt in every home in the land. It has meant that the people not only have greater resources with which to provide themselves with food and clothing and shelter, but also for the enjoyment of what was but lately considered the luxuries of the rich. We call these results prosperity.” Lest the audience take this for granted, however, Coolidge reminded them of the attitude that forged it. “They have come because the people have been willing to do their duty. They have refrained from waste, they have shunned extravagance. They have paid their debts, they have improved their credit. If, out of all these efforts, the reward of prosperity has come, there is reason for national thanksgiving.”

Still, there were very real dangers, Coolidge warned. The Government could not take credit for the prosperity and begin to behave as if the administration of the nation’s finances was a game with a scoreboard to bolster friends or defeat political enemies. There was also the danger that affluence and prosperity would erode the “moral power of the people” by perverting success into something “to be worshiped,” using the rewards of success not to strengthen character or fortify the spiritual condition but for extravagant and disreputable purposes. “Prosperity is only an instrument to be used, not a deity to be worshiped.” In a very practical way, the President was reminding the nation not to lose its way in the advance toward material influence. He kept faith that the people were remembering that in the use of prosperity. He took the audience back to where conditions had been in 1921, the bleakness of depression, the suffering of wartime devastation, and the pessimism that pervaded the country. America was a different place in 1928. Everyone could see it but Coolidge saw the risks that success carried. It did not mean shut down the enterprise and creativity of the country and go back to some convoluted ideal of self-imposed subsistence or “morally superior” decline. It meant be careful with what you have and don’t lose sight of the importance of moral character and spiritual development. The trappings of technology do not substitute for the things that are unseen and eternal. Stuff does not make humanity better, only moral development can do that.

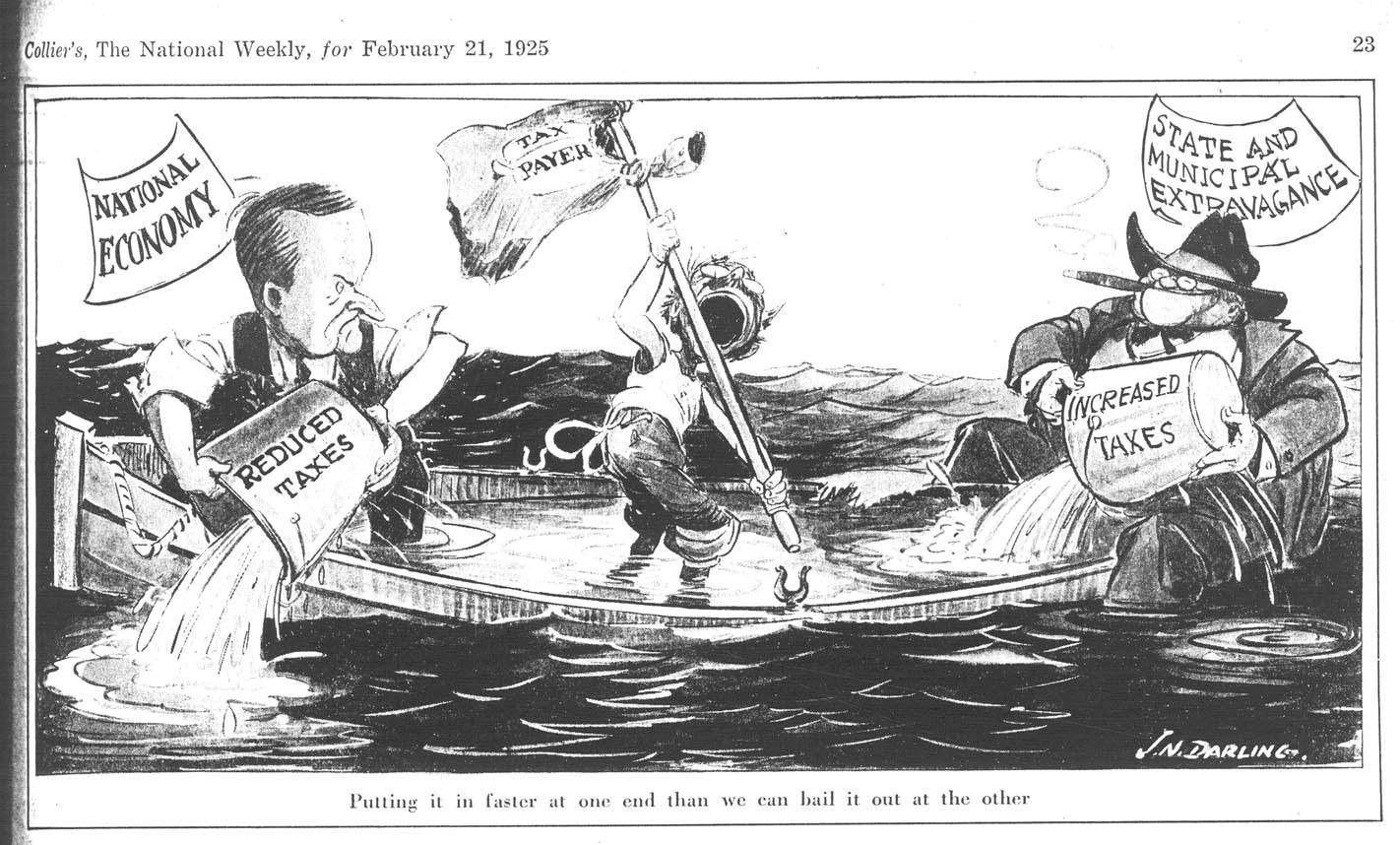

Cartoon by “Ding” Darling, “Putting it in faster at one end than we can bail it our at the other,” Collier’s magazine, February 21, 1925. Courtesy of the University of Iowa.

There were other dangers, Coolidge noticed. While the national government had been commendably moving back in the right and responsible direction, the States and local governments were piling wasteful expenditures into the growth and expansion of their roles. It was equivalent to pouring water back into the boat which Washington had been bailing. It was undoing the gains for which Coolidge and his administration were working. To some degree costs were slowly rising but the spending habits of States and local authorities had gone far beyond that. While Washington had sliced $2 billion from its expenditures between 1921 and 1925, States, counties, and municipalities had ballooned costs by $3.5 billion. Coolidge identified another $500 million had been added in 1926 alone. “This steady increase…is a menace to prosperity. It can not be ignored. It can not longer continue without disaster. It will not correct itself.” This from the man so many mistakenly characterize as “laissez-faire” is revealing. The market would not simply take care of this. It had to be stopped.

The fallout eight months after his departure from public life vindicated Coolidge’s warning. That was not all, however. While his successor, Herbert Hoover, wrote many years later blaming Cal for saying nothing to avert the disaster of Stock Market speculation, he conveniently forgets the President’s next warning. “Another adverse tendency is for people to take their money and use it in speculation, which contributes nothing to the sum of our national wealth.” That, spoken as stock trading was about to skyrocket over the next fifteen months, fell on deaf ears. Blamed years later for the indiscretions of many other people, Coolidge did warn of the danger. Few, if any, were inclined to listen. He can hardly be held responsible for that. His statement later that year, based (ironically) on reports from the Commerce and Treasury Departments. He stated simply on January 6, 1928, that “I haven’t had any indications that the amount was large enough to cause particularly unfavorable comment” and on January 8th of 1929, that “I was advised this morning by the Department of Commerce that the last six months, according to their reports, was better than the first six months of the year 1928…So far as they can determine present conditions in business throughout the country are good and the prospect for the immediate future seems to be as good as usual” (Quint and Ferrell, The Talkative President pp.137-8, 143). These were hardly unqualified endorsements of the prosperity of the country as “absolutely sound” and stocks “cheap at current prices” that Hoover remembers Coolidge saying (The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover p.16). In fact, such statements were even more restrained than the speeches Hoover was giving at the time to reassure the country how prosperity stood on the verge of eradicating poverty and was just about as permanent as ever.

President Coolidge and GOP candidate Secretary Hoover at the White House, 1928. Though only two years younger than Coolidge, Hoover was about as different in temperament and outlook as any one could be from his predecessor. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Coolidge continues his warnings before the Business Organization. Conducting the business of the Federal Government necessitated looking beyond what was required in the present. They had to “look to the welfare of the future as well.” The estimates of the coming year did not guarantee another surplus. It suggested a deficit. This made it all the more imperative for everyone, working together for the same constructive economy, to ensure receipts were not swallowed by expenditures. This would be achieved not merely through a few expansive cuts done for effect. If a deficit was to be accomplished, it would happen through dozens of small savings achieved at every level that would total a large reduction in the end. Coolidge would prevail and the next year’s budget escaped deficit by a sizable amount. This remained to be seen, though, that summer of 1928. “The business of our Government is a real business and it must be conducted as such,” Coolidge reminded them. It impacted the lives of 120 million people and so everyone present that day had to do their part in holding course for the balance of the Budget. Coolidge spoke of the 1930 Budget soon to be laid before the Congress. Setting the cap at $3.7 billion, “the importance of continuing our pay-as-we-go policy…can not be overemphasized.” Preempting the submission of budget requests by the various departments, Coolidge underscored again that “no latitude” existed where law had not authorized it and where conditions did not warrant authorization. They had to work within the limits already set. The President knew they would do their duty.

This still did not preclude commending the expenditures that had increased each year for veterans, made possible by the very discipline they had and must continue exercising with the public money. Federal personnel compensation had been vastly improved, lifting out of its arbitrary and haphazard conditions in 1923 to properly compensating on the basis of merit and ability. The governing principle had never been to avoid all costs but to recognize what befits competence. Just as he was opposed to “overcompensation” he favored an “adequate compensation” that took care of people as valuable assets to good and efficient business. “What we are seeking is justice to the employee and justice to the tax-payer.” If the person on the pay roll was not able to earn high rates of salary – doing the level of work worthy of the pay – that person “should be replaced by those who are more competent.” Under Coolidge, justice to both the employee and the taxpayer would be met.

President Coolidge closed with a brief tribute to one of the great allies in their cause for disciplined budgeting, Representative Martin B. Madden, who had recently died. His chairmanship of the powerful House Committee on Appropriations had been invaluable to the restraint of Federal spending and the continuance throughout the Coolidge years of constructive economy. Though it may been seen as the first notice that the Coolidge Era was fast approaching its close, Cal reminded them that they still had General Lord, the Director of the Budget Bureau, a “great restraining influence upon us all” and the “originating agency of Government economy.” Ever humble, Cal did not take credit even then for what five years of intense work had wrought for the betterment of the country. He, characteristically, turned the meeting over to General Lord and sat down, consistent in the conviction that he was not “Mr. Indispensable” to the nation. Other leaders would rise to future challenges and faithfully serve for the good of all.