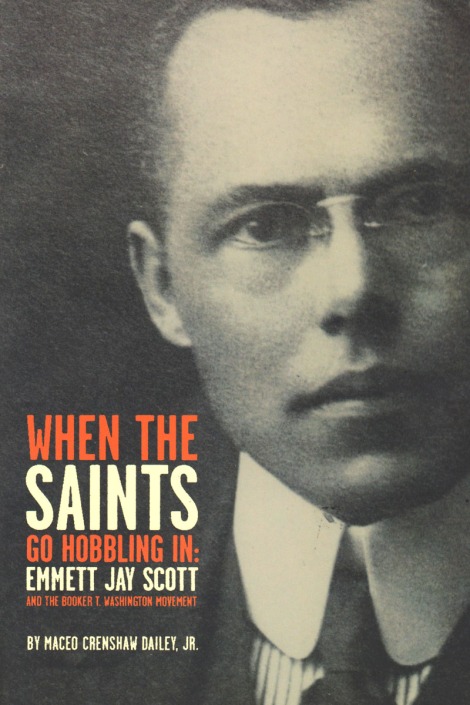

This book is a collection of seven essays composed over the course of thirty years on Emmett J. Scott, the Booker T. Washington movement, and its often denigrated reputation among those who wear the name “scholar.” Dr. Dailey’s lifelong study of Scott, from his biographical dissertation of Scott’s life at Howard University to his more recent writing in journals like Business History Review, equip him to supply a seriously neglected area of historical study. Rebuking the biased tone and outright hostility to Washington and Scott in academia, with their deeply-ingrained refusal to understand them on their own terms, it reminds us that the same tactic has been launched against Coolidge, the contemporary of these two men. Approaching these individuals with a superimposed caricature derived through second hand sources, authors have executed the very same kind of historical hatchet job that has dominated Coolidge historiography as well.

While many academics have come to their task with a conclusion to be forced rather than discovered, even among black historians, Dr. Dailey restores that proper role of intellectual skepticism to challenge the narrative, test received judgments, and overturn the notion that the Tuskegee experiment has nothing to contribute to real solutions on race relations or the civil rights debate. Rather than accepting the prejudicial, even vague, categorization of these leaders as “Uncle Toms” or “accommodationists,” Dailey returns to the deeds, writings, and terms which they used to speak for themselves: “constructionalists.”

In so doing, it illustrates how similar the goals for racial uplift were with Coolidge, who just like Booker T. Washington, believed in the dignity of work, doing the day’s task well, and focusing on the exercise of the liberties of ownership, education of the whole person, entrepreneurship, and service rather than merely criticizing institutions or agitating for political power. Washington, Scott, and Coolidge understood that full political recognition and social equality – already declared in the Constitution and our founding documents – though not fully realized, would come (and were coming) through the industry, character, and judgment of people engaging in commerce, building neighborhoods from the bottom up, and demonstrating the progress of civilization even among those less than three generations before had been slaves. The first object, they knew, was to free the mind of prejudices and obstacles to advancement, and then to get busy exercising the business of independence rather than expecting others to recognize it for them (Washington’s Up From Slavery, written in 1901, sounds remarkably Coolidgean when talking about labor, the artificial versus essential, service, and tolerance, pp.73, 84, 93, 131, 148, 155, 161-2, 165, 182, 188, 312, 208, 220, 223-4, 249, 258, 318). Even Washington’s famous phrase to “cast buckets where you are” (p.219) conveyed the same message of individual responsibility for improvement to which Coolidge appealed, for all people, all his life.

As with any good historian, Dr. Dailey’s essays illustrate his growth as a thinker over the years. Starting from so hostile a position to Washington and Coolidge, it is not surprising that one his earliest essays, “Calvin Coolidge’s Afro-American Connection,” omits a fuller treatment of the Coolidge record and even leaves the reader wondering how this commended the Washington movement at all. That essay, while failing to report a more complete picture in regard to the Coolidge record, still helps supply a gap so wide in race studies of the 1920s that just about anything reported is beneficial to better understand the times and the people. However, as we noted, Dailey does not do justice to Coolidge, faulting him for his reliance on the leaders of Tuskegee at the expense of others in the black community. Dr. Dailey accepts James Weldon Johnson’s incorrect observation that Coolidge, after meeting with him at the White House, seems never to have seen a Negro before, let alone collaborated with them. While that 1923 meeting unfortunately defines subsequent opinions of Coolidge on issues relating to blacks, it is not true. Coolidge, as Dailey notes, recognized fellow Amherst graduate and lone black student, William H. Lewis’ talents early in school. Lewis would later meet with and advise Coolidge after reaching the Presidency and as a liaison between Cal and W. E. B. DuBois, helped secure Dubois’ appointment as the minister plenipotentiary to Liberia, to address Afro-American affairs. DuBois’ quick resignation from that post in disgust at “the system” speaks more to his disdain for working out practical solutions beyond simply finding flaws in the way things were than it besmirches Coolidge, who readily looked outside Tuskegee for able problem-solvers.

Regrettably, Dailey, by accepting James W. Johnson’s hardly unbiased assessment of Cal, overlooks a longstanding collaboration with and support for influential blacks beyond the Tuskegee sphere. Senator Coolidge rendered crucial support for the Boston firebrand Monroe Trotter in 1915, casting the necessary vote to prevent reconsideration of the Boston ban on showing Birth of A Nation, D. W. Griffith’s racist film, despite it being a project openly praised by President Wilson. Coolidge would go on to meet, as President, with Trotter and listen to advice from such diverse views as A, Philip Randolph, members of the Associated Negro Press and the NAACP. His quiet manner in these meetings, speaking little and promising nothing, while a mystery to many a petitioner, illustrated his way of receiving everyone. It was not an expression of ambivalence or indifference to the audience. It manifested the old adage of one being best able to listen when not talking. As Vice President, he would travel to Atlanta, the heart of the Old South, for the Southern Tariff Congress, and speak to and meet with members of the black community during his visit there. The community in Atlanta, centered around Auburn Avenue, where Dailey notes, operated the largest concentration of black businesses anywhere in the country (166-167). When the time came to act, as it did against lynching, in favor of appointment of qualified men and women to public posts, against confirmed instances of departmental segregation and bigotry, and in favor of greater political representation, through party delegations and candidates like Dr. Roberts of Harlem, Cal proves to be one of the most conscientious advocates blacks had in the 1920s.

All of this escapes inclusion in Dailey’s view of Coolidge, however. It is never mentioned that while the Democrat Party, devastated by its approval of the Klan, tried in vain to live that legacy down without alienating its support base in 1924 tried in vain to project the conflict onto Coolidge. While Democrats and Progressives wrangled in a battle of words, Coolidge simply met with the very groups the Klan was targeting without ever providing the rhetorical fuel and free publicity his opponents were seeking. While some endorsed Cal to discredit his campaign, he went to black baseball games in the D.C. area, addressed Howard University, met with black entrepreneurs, collaborated with Emmett J. Scott and William Matthews, held interviews with black journalists, even hostile ones like the regular columnist “Hezekiah” of Philadelphia, drew upon the administrative talents of Mrs. Mary Bethune, Mrs. Hallie Brown, the grassroots work by the ladies of the National League of Republican Colored Women, kept naming blacks to federal offices from Judge James A. Cobb to Customs Collector Walter Cohen to the first ever all-black diplomatic team dispatched to study and report on conditions in the Virgin Islands. It never seems to occur to “scholars” that Coolidge’s tax reduction and constructive economy programs were as much civil rights achievements as anything more overt. By enabling people to work more for themselves and less for government, it would furnish the environment that was the boom of the 20s, enhancing opportunities, not merely for whites but for everybody to a level never experienced before. Moreover, this came at the culmination of a quarter century that had seen incredible advancement, by every measure, in property ownership, wealth creation, and raised standards of living felt by blacks, realizing what being free meant. It was a time of vibrant institution building and construction of culture, commerce, and churches that had been non-existent three generations before. All this and more never makes it into the “official” narrative but it belongs there right beside Coolidge’s other accomplishments in tax and debt reduction as well as flood relief, air and radio development, and reforms in the judicial system.

Dailey’s book renders a substantial service to an area of study misunderstood from downright neglect for far too long. It does not bridge the gap but it certainly supplies crucial building materials upon which to reach a fuller view of the importance of the Washington movement and Coolidge’s contributions toward racial healing and progress as Americans together.

We give this book 3 1/2 stars.

‘Coolidge, who just like Booker T. Washington, believed in the dignity of work, doing the day’s task well, and focusing on the exercise of the liberties of ownership, education of the whole person, entrepreneurship, and service rather than merely criticizing institutions or agitating for political power.’

This is why I have admired Coolidge and Washington since I studied in depth on the two back in high school and college. These traits produce people who don’t need much government in order to survive. Not many politicians are interested in those kind of people any more.