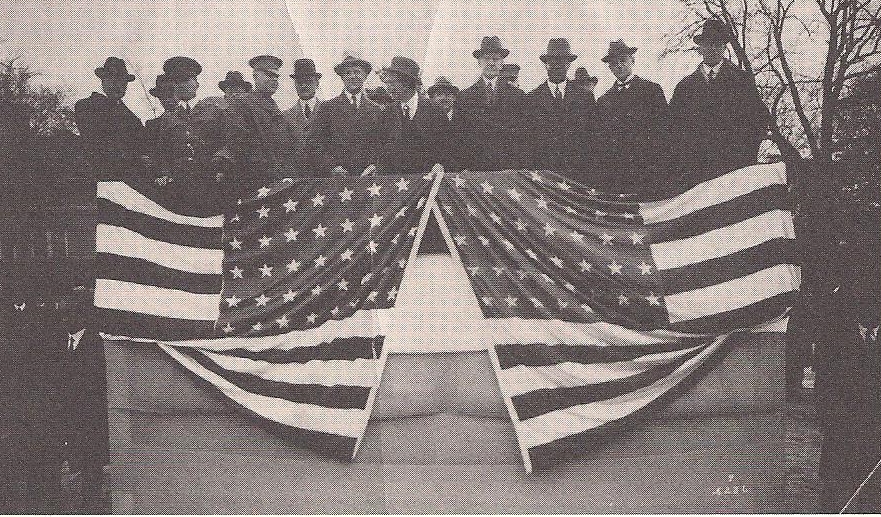

Gathering at the dedication of the hospital for veterans at Tuskegee, 1923. Then-Vice President Coolidge stands center above the flag to the right, to his left is Dr. Robert R. Moton, President of Tuskegee. Photo courtesy of Dan T. Williams, Archivist at Tuskegee University.

Many a social reform takes years to be implemented. Those deemed, in some places, outside the equal protection of the law have been known to wait for decades – sometimes centuries – all across human history before finally seeing a fair and just return recognized. We have written before here regarding three such instances during the Coolidge years alone. His era, collectively characterized as a hopelessly nativist period, actually furnishes valuable insight to the greatness of America’s ideals, not their repudiation. It is useful to study Coolidge and his time not with the arrogant blinders of moral superiority, denying our own ignorance and prejudices, but starting any study of human experience with genuine humility, without which we will fail to learn anything of importance. We will remain just as blind, if not more so, as we presume other generations to have been.

First, we have noted here that it was Coolidge who recognized the exceptional work being done at Tuskegee, the institution that would produce, as a whole, the finest tradesmen and airmen of World War II. It was Coolidge’s understanding of the potential of institutions like Tuskegee, Howard University, and others that brought his typically covert pressure – a pressure applied through subtle conversation in small meetings and the renowned clarity of his public speeches – to greatest effect. His six Annual Messages were his most direct opportunities at taking his whole agenda straight to the people via the platform aimed at Congress. He did not threaten or public malign but he applied pressure nonetheless with every nationally broadcast utterance. Within his first year he had secured generous appropriations to both institutions, and would see those amounts increase before leaving office.

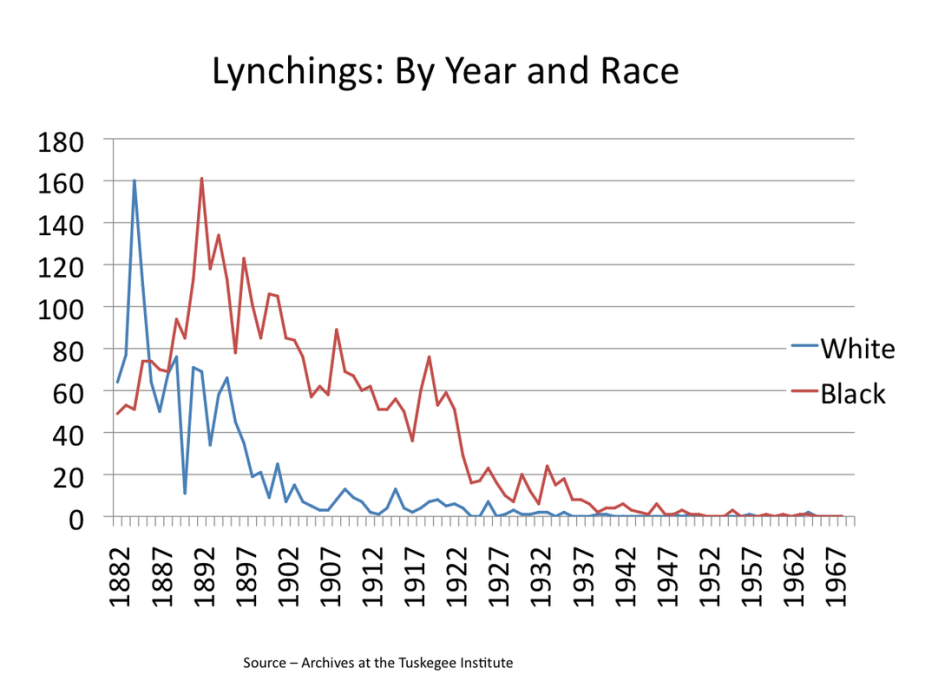

Second, while some accuse Coolidge of “dropping the ball” when it came to lynching, the record bears out that by the end of his term, he was the only one still seriously talking about its removal and criminalization under federal statute, as his final Annual Message confirms. Meanwhile, the number of lynchings continued to drop throughout the Coolidge years, no less due to the economic environment fostered by the President’s policies than by his regular insistence that Congress take up the matter again and finally address it. He persisted in reminding Congress every year for six years what it had failed to do in preventing another Democrat filibuster against it as happened back in 1922. Too intimidated by renewing legislative combat to reopen the issue, the Congress ignored the President’s position and no action was taken. It would serve as an ineradicable prick to the conscience in the years to come that a President of the United States had defended the rights of all people, as obligated under our Constitution and laws at a time when it was anything but politically beneficial to do so. Refusing to let the issue go away quietly, Coolidge was not silent on the race problem, even before audiences who remembered the violence in Omaha (where he condemned intolerance and bigotry before the American Legion), the struggle to properly provide care for black veterans at Tuskegee without prejudiced white management (where his involvement ensured black administrators, nurses, and doctors operated there independently for the first time), and the need to desegregate government facilities again, especially in the worst offenders at the Public Lands section, Census Bureau, Interior, Commerce, and Labor Departments, after the regression of the Wilson years (where departments found to have committed specific instances of segregation learned firsthand how fiery a temper Coolidge could unleash on perpetrators of such wrongs).

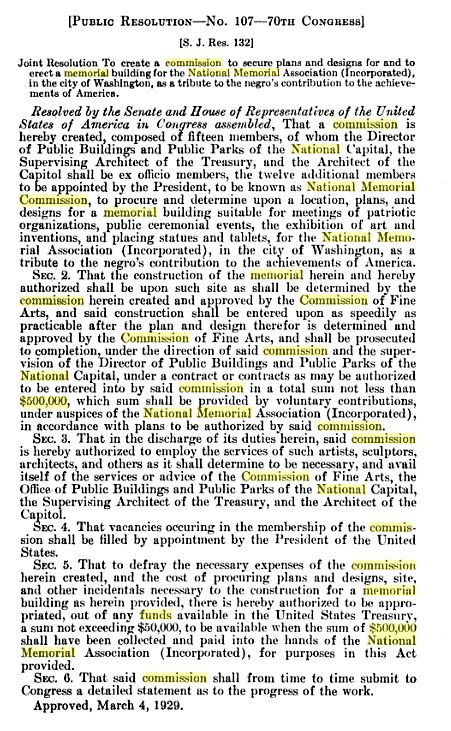

And third, Coolidge took the first step to finally recognize the contributions of black Americans to the country. A devoted group, known as the National Memorial Association, had been trying for fourteen years to secure this goal. It was Coolidge who became the first to do something about their quest. Having personally seen the bravery of veterans during the Great War, having honored one such veteran with a visit to the White House (“Harlem Hellfighter” Henry “Black Death” Johnson, whose deeds warranted the recognition that would finally come to him posthumously in 1996 and 2001), and having seen what strides were being achieved institutionally and economically through the hard fought march to equality by Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, Robert R. Moton, Thomas Lee, Emmett J. Scott, A. Philip Randolph, James A. Cobb, Giles B. Jackson, Blanche Bruce, Maggie Walker, Georgia D. Johnson, “Duke” Ellington, Monroe Trotter, Hattie Brown, Mary Church Terrell, Bessie Smith, Mary Bethune Walker, Walter Cohen, Paul Revere Williams, William Matthews, George H. Woodson, George W. Carver, William Lewis, W. E. B. DuBois, Jefferson S. Coage, Arthur Brooks, John R. Hawkins, and countless others, Coolidge signed on his last day in office what became Public Law 107, which reads:

“That a commission is hereby created, composed of fifteen members…to be known as the National Memorial Commission, to procure and determine upon a location, plans, and designs for a memorial building suitable for meetings of patriotic organizations, public ceremonial events, the exhibition of art and inventions, and placing statues and tablets, for the National Memorial Association (Incorporated), in the city of Washington, as a tribute to the negro’s contribution to the achievements of America…”

The law went on to state that the Commission would be appropriated $50,000 from the Treasury after it raised $500,000 in private funds, reporting its progress, toward this goal, to Congress from time to time. Sadly, the Depression intervened and those funds were never raised thereby precluding the subsequent provision under the law from the public Treasury. It would not be until the 1960s that mention of this commission and its work would begin anew. It would take another forty years, when in 2003, President Bush signed a renewal of the law his Vermont predecessor had approved that the the resulting development of the Black History Museum would at last take shape, finally underway this year (as the video below depicts). Cal will likely not appear anywhere on the site of this Museum nor feature in any of the displays recognizing the historical achievements of Americans in realizing the contributions of so many to our experience in individual liberty and self-government. He nonetheless brought this long overdue recognition to life nearly nine decades ago. It all began with the brave step he took on March 4, 1929.

When he could have left the whole business to his successor, he would not see it relegated to chance and ensured that at least the cause (as important as it was) would be championed, the law would be born, the commission created, and the money authorized. Blacks in America were no less worthy of the same honor that goes to whom it is due, no less deserving of the same rewards of full citizenship that came through the hard-fought march of generations, whatever their ancestral home, be they the Irish, the Chinese, the Japanese, the Italians, the Slavs, the Polish, or anyone else. As Coolidge put it to one audience, “Whether one traces his Americanism back three centuries to the Mayflower, or three years to the steerage, is not half so important as whether his Americanism of today is real and genuine. No matter by what various crafts we came here, we are all now in the same boat.” He took pains to ensure all Americans realized full participation in that shared experiment, that we could recognize each other as equals, fellow travelers, and that we could live together in peace and still live free. Cal’s actions throughout his public life, including this, among the last of his official acts as President, strove to see that the colorblind equality proclaimed in the Declaration and made possible by the Constitution be no less cherished in his day and time. It is the ideal America means to us all.

Is the name of the museum REALLY National Museum of African American History & Culture? That is disgraceful for anyone who would put America first. My God! Wake up, people! They are sending you back to Africa in a museum that looks like a giant boat on top of a sacrificial alter! I love all of my American brothers who would see themselves as equal and not be programmed by the elites! Please don’t let these elites do this to you as individuals. We fought many wars for the freedom of individuals…so that we each would not have to be grouped in any other way than as Americans.

Well said!