It is regrettable that Professor Timothy Moy is no longer with us, having died in 2007 in a tragic attempt to rescue his son from the surf off the Hawaiian coast. Moy wrote a superb book, published in 2001, on the institutional identity, doctrinal development, and technological innovation of the Air Corps and Marine Corps from the 1920s to the eve of World War II. It is a fascinating look at a largely neglected subject. It is a fine companion to John T. Kuehn’s Agents of Innovation: The General Board and the Design of the Fleet That Defeated the Japanese Navy, which focuses on (as the title indicates) the simultaneous endeavors of the Navy to overcome the challenges imposed by the political forces, technological limits, and institutional outlooks of the 1920s and 30s.

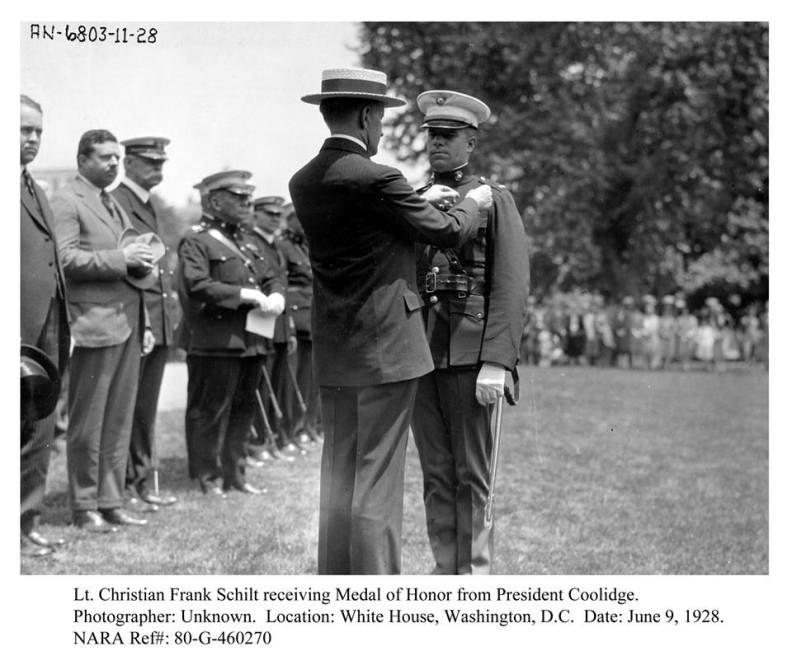

While President Coolidge plays merely a supporting role in the developments of this era. Moy reminds us of a principle Coolidge often voiced, the spiritual must precede the material. Such was the case with the Air Corps and Marine Corps. Moy points out that both, possessing distinctive institutional identities, had to reinvent visions for themselves to step forward into the future. The attitude and the dream had to come first. The technological advancements and even institutional permanence would follow only after the creation of a vision of who each was and what its purpose should be.

The Air Corps envisioned itself as the high-tech knights of the sky, bringing war to a higher art through precision bombing. Meanwhile, the Marines embraced the identity of the low-tech all-purpose warriors, carving out the unique turf of advance-base, amphibious warfare. Once these fantastic, even outlandish, visions had been imagined the late 1920s into the 1930s would produce the tactical training, the testing of equipment, and finally the production of materiel that just a few short years before had been impossible. The imagination, freed to design and adapt, became reality as blueprints were built into the tools that both the Air Corps and Marine Corps would introduce to the world, with incomprehensible results and devastating effects, during World War II.

The B-29 “SuperFortress,” the Norden bombsight, the LCVP “Eureka,” and the Higgins’ hinged bow ramp were, as Moy observes, anything but foregone conclusions. There was no inevitably logical process that produced these amazing leaps in technology. Nevertheless, they grew out of the institutional identities and collaborative visions born in the 1920s. It was that decade, with all its optimism in hard work and the attitude that no dream is impossible with persistent effort, charted and informed the direction each took to stake out its significance and move forward.

The Washington Arms Limitation Conference in 1921-22 certainly set the basic parameters of where America allowed itself to go in the next twenty years. However, significantly, Coolidge, as Commander-in-Chief (even through the failed Geneva Conference and annual budget fights), did not attempt to micromanage the planning, R & D, or institutional purposes of air power or the Marine Corps, as Hoover would later try through extensive cuts in personnel and funding. The Washington Conference, having placed obstacles on the contingency and war plans of Army and Navy, Coolidge wisely did not indulge a temperament of dictating how each branch would get around the challenges presented to them. He left that to those closest to the situation, the officers and enlisted men themselves in each service. They were the best experts to solve the problems politicians and bureaucrats had imposed.

The Conference, in extracting concessions from Japan, promised that no bases would be built or reinforced in the Pacific. This clause created more problems to the Navy and Marine Corps than anything else could. Though the administration differed with the military on the basis of “good faith” between nations: The military believing the other signatories needed to show “good faith” first by enacting the limits upon which all had agreed whereas the administration believed the United States needed to exemplify “good faith” for the others to follow. In the end, as the failure of the Geneva Conference in 1927 illustrated, the other signers were anything but impressed by the American example of “good faith,” as both Britain and Japan had been cheating on the agreement, the former using legend tons as opposed to standard tons and the latter outpacing the U.S. in naval construction, defying the original 5:5:3 ratio.

It showed Coolidge that the United States had been suckered in, something he personally despised learning. He corrected course and signed the largest naval construction legislation of his tenure, providing for fifteen cruisers and one carrier. Through it all, Coolidge could have camped in the Navy and War Department offices, setting the exact terms on which each ought to develop its personnel and technology. He could have deployed the bureaucratic machines in Washington to inject themselves in the process. He did none of these things. The credit for the solutions the Navy, the Air Corps, and the Marines would discover belonged, rightly, to those most directly involved. They were the best qualified experts, not politicians. He left all this for others to work out, and they did. The development of carriers – self-sufficient mobile bases – in lieu of land sites, with all the tactics and strategy this entailed, became the Navy’s answer to their part of the dilemma. The speed, range, and capabilities of strategic bombers, instead of merely improved fighter planes, became the answer of the Air Corps. This was set to overturn the conventional wisdom in military aviation, breaking the deadlock witnessed in trench warfare during the First World War. Also overturning conventional tactics and strategy was the Marine Corps’ preparation of amphibious campaigning, answering the problem of what could be done about no launching point in the Pacific should Japan attack, as “War Plan Orange” speculated. By capitalizing on the exceptional capabilities of the Higgins’ Eureka, the LVT (“Alligator”), the logistical complications of landing on hostile shores, and the creation of the flamethrower all combined to furnish the Marine Corps’ answer to the problem.

While no one can honestly claim that Coolidge somehow deserves credit for all this innovation, he did, even unwittingly, help encourage its development. Coolidge’s budgetary discipline, while appropriations for the military continued to rise each year of his administration, did little to fund expansive projects or convert ideas into concrete tools. However, as we noted above, the vision had to be worked out first. Throwing money at this or that concept, before giving the overall picture time to solidify in the minds and attitudes of each branch would have been wasteful and likely not yielded the final results. He made plain in his Budget statements that for national defense to remain adequate, as opposed to bloated and profligate, the problems presented to each arm of the military would best be met through industrial means. It would be the brains and resourcefulness of industry that would solve – fixes seen only dimly in the 1920s – the issues each had to face to become better. It forced each element of our military to distill down the most essential goals and their most important means to accomplishment from what otherwise would be a Christmas list of superfluous wants subordinated to truly necessary functions. It forced everyone to more carefully sift through the minutae and understand what was most important to each branch’s purpose. This brought them to realize their most efficient best, than otherwise would have been the case. The credit, of course, goes to the inventors, officers, and men who made these decisions.

Moy’s book is concise, and though there are a few repetitions and tedious passages, it presents an intriguing and inspiring picture that contradicts the accepted notion that the 1920s were uneventful, uninteresting, and inconsequential to America or to the world. Coolidge’s part in this element of the overall picture is minor, a supporting actor in the production, but his role remains consequential to the outcome. Had there been a micromanager (like LBJ) in the White House, a President who personally set the parameters for unit-to-unit decision-making on the ground, or had we been fast and loose with public money, expecting that to automatically translate into powerful and beneficial innovations, we would not have seen the fruits of so much hard work by so many.