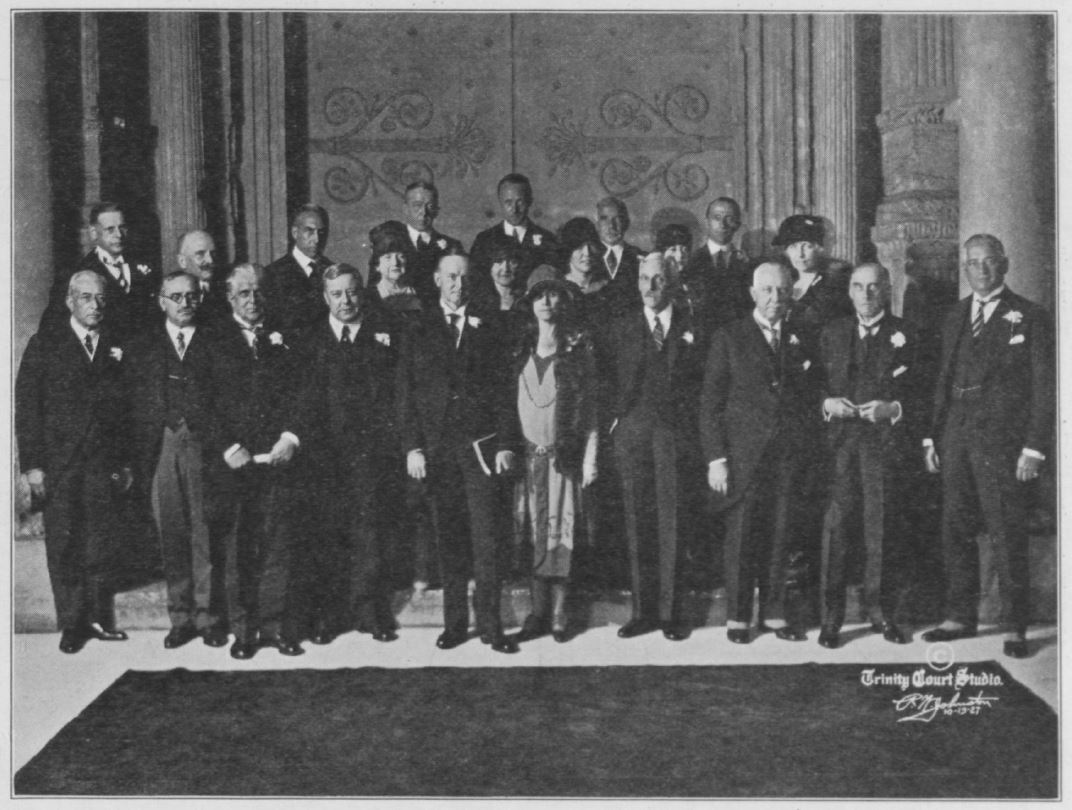

President and Mrs. Coolidge at the opening day of the Carnegie International Exhibition, Pittsburgh’s Music Hall, October 13, 1927. First Row: George Cretziano, Paul Claudel, James J. Davis, Daniel Winters, Mr. and Mrs. Coolidge, Andrew W. Mellon, Richard B. Mellon, Samuel Harden Church, Charles H. Kline. Second Row: Edgar Prochnik, J. H. van Royen, Rev. Dr. John Ray Ewers, Mrs. Richard B. Mellon, David A. Reed, Madame Prochnik, Robert Silvercruys, Mrs. Davis, Otto H. Kahn, Mlle. Cretziano, Count Marchetti, and Mrs. Church.

Eighty-eight years ago today President Calvin Coolidge rose to the podium in Pittsburgh’s beautiful Music Hall at the Carnegie Institute and addressed the large gathering there on the opening day of the 26th International Exhibition. The exhibition, featuring 400 paintings by some 80 artists from around the world, included 30 Americans, ran for two months. Director Homer Saint-Gaudens would hold his popular vote for the best pictures, awarding prizes to those artists chosen by the thousands of visitors as representing the best art in that year’s display. Art, speaking as it always does both to and about the culture, was in transition and 1927 would mark the first year a modern-styled piece would be recognized with First Prize, the honor going to Henri Matisse for his “Still Life.”

The room where President Coolidge addressed the gathering at the opening day of the 1927 International Exhibition, as it looked in 2012.

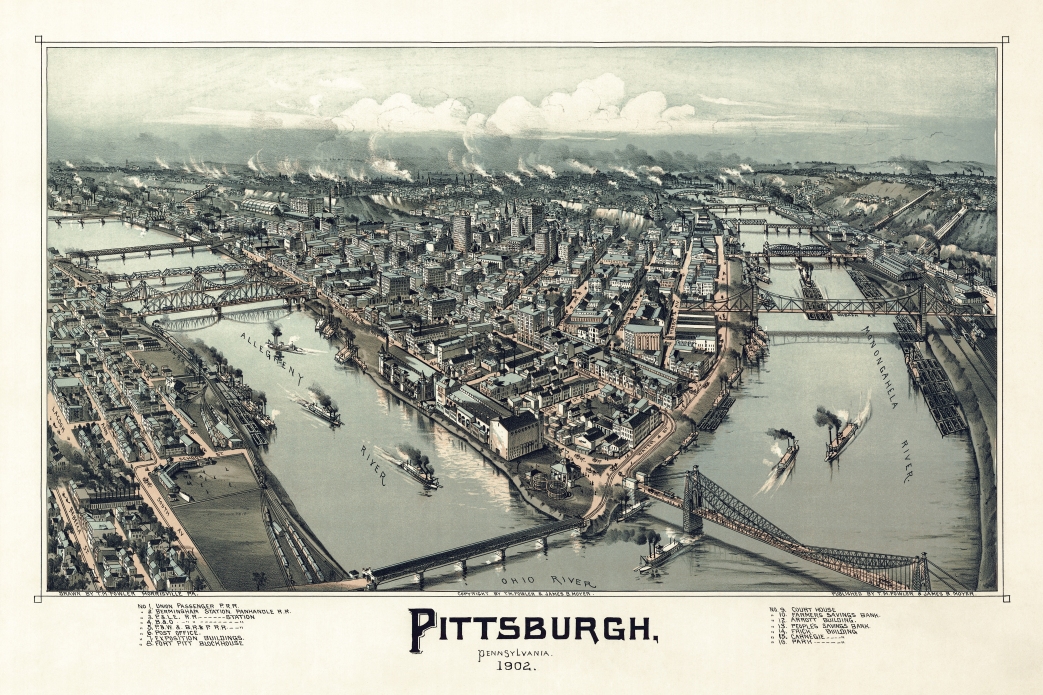

As Coolidge spoke to those present in the hall that day, he reminded the audience of where they stood and how it had not been that long ago when Pittsburgh was a rugged, frontier town of some twenty log houses. In less than 150 years it had accomplished preeminence in manufacturing and commerce in what most would expect required centuries of slow, incremental management. Pittsburgh had shown it could be done in far less time. However, as Coolidge points out, this was not some mystical or fortunate accident, it was attributable to “a supreme effort…the making of sacrifices that reached to life itself, by the endurance of long years of war and unending toil through many years of peace.” America itself had been forged, not by mere happenstance, but from people “who could face facts and were willing to grapple with realities; from men whose hands were hardened at the plow, whose faces were blackened at the forge, whose bodies had been exposed to the fire of hostile forces. These are,” Coolidge told the crowds that day, “the foundations on which our country has been built.” Out of all that hard, difficult work has come what he called “the flower of our civilization” not only in the “guarantees of liberty” but in its ability to harness “enormous material resources,” cultivate “educational institutions,” and blossom with the “beauties of architecture…sculpture…music, and…painting.”

Pittsburgh was a living illustration of what had transpired all across the country as “every important center of population” came into being. It was echoed in the lives of those who contributed in the making of our country, as the hardships and experiences of George Washington in and around what would become Pittsburgh, attested. Even as Pittsburgh would carve a place on the frontier, the people who knew such challenges firsthand, living daily with muskets in hand to defend their rights from arbitrary authority, did not merely think of the present or themselves alone. They gave careful thought and investment to the education of the mind, the betterment of the spirit and the practical training of the hands. As commerce continued to move west, the Pennsylvania Railroad came to Pittsburgh in 1854, setting the stage for 70 years of intense effort to hew out the thriving city it would become. It was practical art, Coolidge explained. Like the potential of a blank page or empty canvas, the people who toiled for and created what would be Pittsburgh from the wilderness were “making ready to write that wonderful epic of coal and oil and steel, paint that inspiring landscape of hillside and water front, decorated by gigantic commercial structures throbbing with the movement of industrial life and surmounted by cloud and fire.” They were actualizing the principles of “progress to the affairs of this life,” Coolidge declared. It was not an exclusive club of creative labor but a collaborative project to which people from distant locales came to contribute toward the rise of its leading place in mining coal, treating coke, forming glass, engineering electrical machinery, and taking its place among the greatest seaports and financial centers of the world at that time beside New York, Boston, London, Antwerp, and Hamburg.

This was not unique in America, Coolidge repeated, it had come about all across the land distributing widely its rewards to the meanest community and humblest household. Like an unfinished portrait, it was by no means complete but it had come a long way with the principles behind all the prosperity. “The question for the determination of the American people,” the President noted, “is no longer whether they will be able to secure prosperity” but rather “what use they will make of” that success. “It is only in its use that we can justify its existence.” Material affluence was empty and meaningless otherwise, Cal said. “The answer will undoubtedly be found in the religion, the education, and the art of the people.” Time and experience had already shown that the means acquired by the people of America was not being squandered to “selfish indulgence” and “ostentatious luxury” but “used to raise the life of the people into a higher realm.” This was why the Carnegie International Exhibition was so important as much more than a statement of vain pretense but as a recognition of the real evidence of success present around the fireside of “happy and contented homes,” the “mental and moral life of the people.”

The President then turned to the namesake of the institution in which they stood, one of Pittsburgh’s great citizens, Andrew Carnegie. Though Mr. Carnegie was not present that day, having died in 1919, his “deep love of humanity and desire to promote” the practical betterment of people materially, mentally, and morally were present. Immigrating as a child, he quickly recognized the value of steel in the service of humanity, using wealth not as it had been so often placed for the enrichment of a few elites in the Old World but putting it to work for all people. The very Hall around them spoke of this ideal with its library of 622,000 volumes (widely used by the people of Pittsburgh), its museum of natural history, and (the reason for their gathering that day) its gallery of fine art. Carnegie’s adherence to the practical kept these goals from merely soaring in the realm of what could be but brought them to what is and what should be. Encouraged by the “sturdy character” of his parents, Carnegie received his highest education in the schoolroom of practical experience.

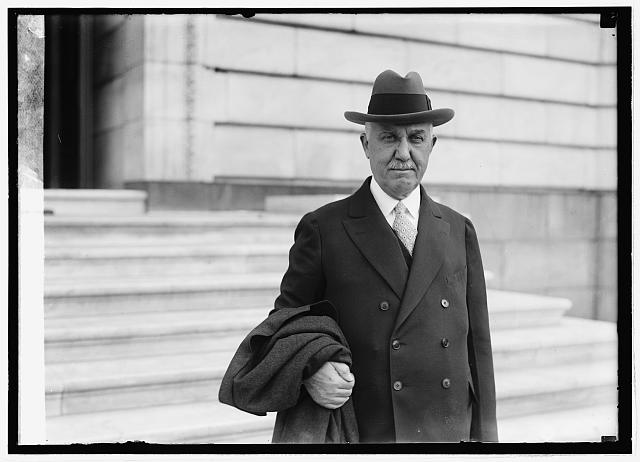

“Good thoughts and good deeds have an inherent power for development,” Coolidge would assert. “They grow and expand.” When the gallery started in 1896 (for which they had assembled that day) it began as a local effort to benefit the people of Pittsburgh. It quickly took on “the nature of an international institution.” That year’s Exhibition would involve 15 countries, and not only participate with the Brooklyn Museum of Arts and Sciences but “go west” for the first time, across the Rocky Mountains to San Francisco. As Coolidge could have reiterated at this point, none of this happened by magic, it was the result of the hard work of many people. Two of them, present that day, were crucial to its success, however. It required people with generous hearts and a keen sense of their duty to others. Those two men, distinguished citizens of Pittsburgh, were Andrew W. Mellon and his brother, Richard B. Mellon. “They stand out as men who are devoting themselves to the service of humanity, one by remaining as a leader in great financial and industrial enterprises and the other by turning his great talents to the administration of public finance as Secretary of the Treasury of the United States, where his leadership in the last six years has been greatly instrumental in restoring the economic equilibrium of the world.” This is but one example of what continued to be transpiring throughout the nation by men and women with the hearts and means to give for those around them.

Richard B. Mellon, Andrew’s younger brother, closest friend, masterful business partner, and great philanthropist of a generous family

Coolidge concludes his speech with the recognition of the exhibition’s dual character, as both international and distinctly American. While the old masters of painting were to be revered for their work, Mr. Carnegie had ensured that this event would underscore how ongoing creation must be. People must continue to create for progress to be sustained, providing for the purchase of “not less than two American pictures painted within the year” to be added to the gallery. Art visualizes the values and character of nations. Coolidge understood this and its encouragement inspired him. By engaging in this “generous rivalry of well-doing” it conferred all who took part in it an appreciation of what makes art truly art and elevates our relationships with those around us.

Gilbert Stuart, Self-portrait, was the artist best known for giving us the now-famous faces of George Washington and many of his generation.

Benjamin West, Self-portrait, 1763. It was West who gave us many of the lush historical scenes of the Revolutionary Era and inspired a number of artists after him to do the same.

Lest the audience forget, however, Coolidge then devolved on what made this occasion so distinctly American. America had unquestionably taken its place among the foremost of nations in the adornment and quality of its art. From the days of Gilbert Stuart and Benjamin West through Whistler, Abbey, and Sargent, on to contemporaries like La Farge, Homer, and others, America was proving inside of two centuries that it was no less inferior to the oldest empires of the Old World in its artistic contributions. Built on the foundations “that freedom, education, and wealth are not to be reserved for the few, but are to be reached through equal opportunity which is open to all,” America had “staked” its reasons for being “on the potential capacity of the average citizen.” America was underscoring the ideal that “truth and beauty are inseparably related.” The art of America proclaimed it. Its art would have to continue to proclaim it for that ideal to remain in its proper relation to the nation’s future actions. By observing that ideal, keeping truth and beauty inseparably connected, America’s art would “raise people to a spiritual level which they could not otherwise attain.”

Edwin Austin Abbey’s Apotheosis of Pennsylvania (1908-1911), Pennsylvania State House in Harrisburg.

Coolidge knew America’s pursuit of these ideals had not, and would not, arrive at perfect completion. Like a blueprint of any majestic structure, however, America had laid out the fundamentals of the plan. Coolidge praised this, knowing that “enough has been done so that we know we are going in the right direction.” It would not be carried by simply one man, as Mr. Carnegie would resolutely maintain, but had been and would continue to be a “joint effort” by everyone: from great leaders like Carnegie as well as “all those associated with him,” sharing his outlook, “down to the humblest worker in his mills.” All were important to America. All had a share in its continued success. America, like the Exhibition, required just as much the collaboration and cooperation of all its people if the future was to move forward and onward.

Frank Ashford’s portrait of Calvin Coolidge done in South Dakota the summer before this speech at Pittsburgh. Depicted in the headdress gifted to him there, the President presents a colorful profile as he gazes contemplatively into the distance.

Looking back on this day, eighty-eight years ago, it continues to speak to the ideals true art represents and that America is only going to continue to advance through the hard work of its people, the real kings and queens of this experiment in self-government. It was they who carved something better for everyone out of the wilderness and, inspired by something more than material affluence, strove mightily for the mental and moral advancement of us all. Uniting truth with beauty, they did more than dream, but they designed and created, toiled and sacrificed. It is that exceptional landscape that enables us to enjoy its breath-taking vistas now. The growth of the future will not rest with those who fail to understand this, to see only selfishness and exploitation in the “rattle of the reaper, the buzz of the saw, the clang of the anvil, or the roar of traffic.” Instead, Coolidge saw all of these endeavors forming “part of a mighty symphony, not only of material but of spiritual progress.” As Coolidge looked out over his audience, seeing the inspiring accomplishments of Pittsburgh beyond, and the fruits of an America confident in the truth and beauty of its ideals, he said, “Out of them the Nation is supporting religious institutions, endowing its colleges, providing its charities, furnishing adornments of architecture, rearing its monuments, organizing its orchestras, and encouraging its painting.”

The nation was more than its government administration, bigger than its politics, and larger than its politicians. Critics see merely all the flaws and fissures of human existence in order to complain about them, “But,” Coolidge affirmed, “the American people see and understand. Unperturbed, they move majestically forward in the consciousness that they are making their contributions in common with our sister nations to the progress of humanity.” Rather than succumb to all the distractions of inadequacy, Americans were demonstrating that they directed the nation’s course, and if improvements were to be made, they had to step up and take charge of them, all the while remembering the spiritual things, the obligations not only before God but to our fellow man.

Pingback: On the Performing Arts | The Importance of the Obvious