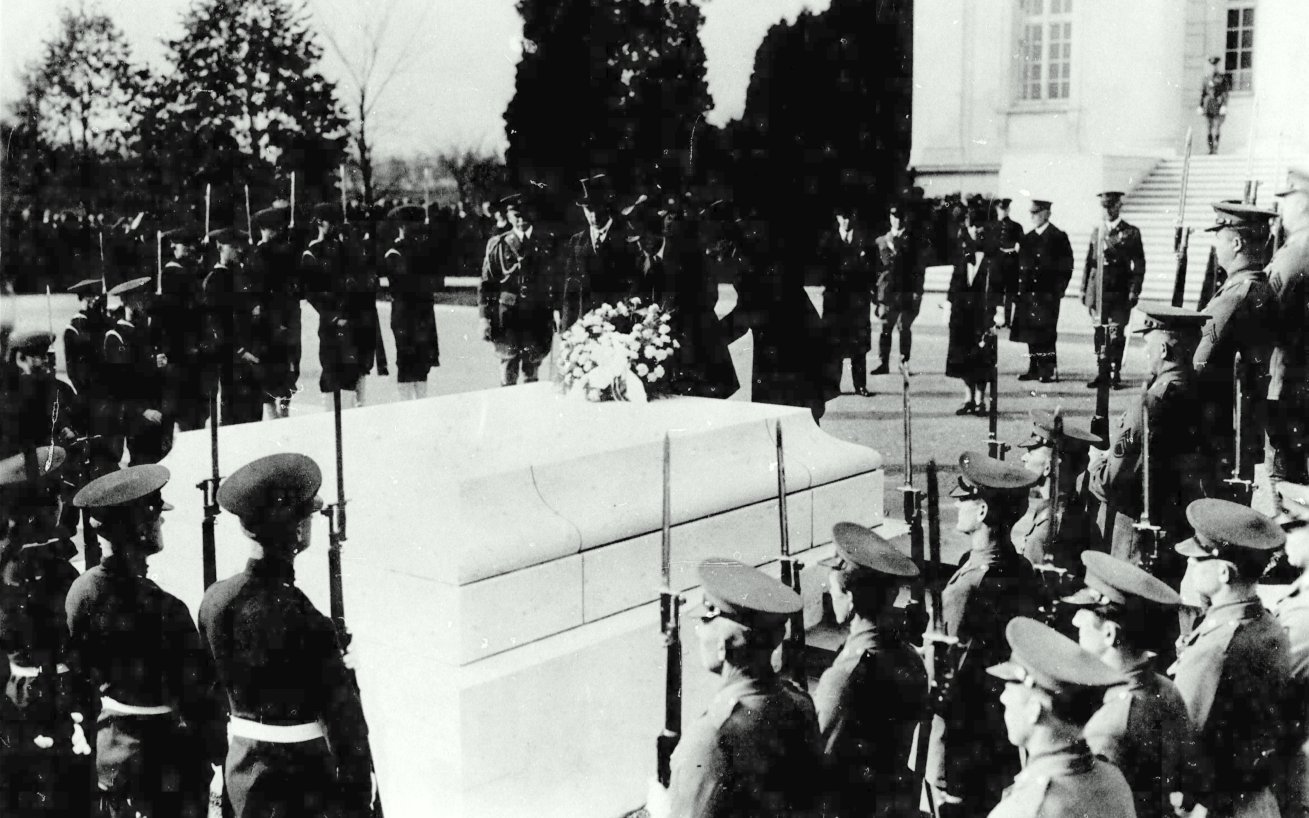

Washington Auditorium, 1926, two years before Coolidge’s speech marking the tenth anniversary of the Armistice.

“Every dictate of humanity constantly cries aloud that we do not want any more war. We ought to take every precaution and make every honorable sacrifice, however great, to prevent it. Still, the first law of progress requires the world to face facts, and it is equally plain that reason and conscience are as yet by no means supreme in human affairs. The inherited instinct of selfishness is very far from being eliminated; the forces of evil are exceedingly powerful.

“The eternal questions before the nations are how to prevent war and how to defend themselves if it comes. There are those who see no answer, except military preparation. But this remedy has never proved sufficient. We do not know of any nation which has ever been able to provide arms enough so as always to be at peace. Fifteen years ago the most thoroughly equipped people of Europe were Germany and France. We saw what happened. While Rome maintained a general peace for many generations, it was not without a running conflict on the borders which finally engulfed the empire. But there is a wide distinction between absolute prevention and frequent recurrence, and peace is of little value if it is constantly accompanied by the threatened or the actual violation of national rights.

“If the European countries had neglected their defenses, it is probable that war would have come much sooner. All human experience seems to demonstrate that a country which makes reasonable preparation for defense is less likely to be subject to a hostile attack and less likely to suffer a violation of its rights which might lead to war. This is the prevailing attitude of the United States and one which I believe should constantly determine its actions. To be ready for defense is not to be guilty of aggression. We can have military preparation without assuming a military spirit. It is our duty to ourselves and to the cause of civilization, to the preservation of domestic tranquility, to our orderly and lawful relations with foreign people, to maintain an adequate Army and Navy…

“So long as promises can be broken and treaties can be violated we can have no positive assurances, yet every one knows they are additional safeguards. We can only say that this is the best that mortal man can do. It is beside the mark to argue that we should not put faith in it. The whole scheme of human society, the whole progress of civilization, requires that we should have faith in men and in nations. There is no other positive power on which we could rely. All the values that have ever been created, all the progress that has ever been made, declared that our faith is justified.

“For the cause of peace the United States is adopting the only practical principles that have even been proposed, of preparation, limitation, and renunciation. The progress that the world has made in this direction in the last 10 years surpasses all the progress ever before made…

“We have heard an impressive amount of discussion concerning our duty to Europe. Our own people have supplied considerable quantities of it. Europe itself has expressed very definite ideas on this subject. We do have such duties. We have acknowledged them and tried to meet them. They are not all on one side, however. They are mutual. We have sometimes been reproached for lecturing Europe, but probably ours are not the only people who sometimes engage in gratuitous criticism and advice. We have also been charge with pursuing a policy of isolation. We are not the only people, either, who desire to give their attention to their own affairs. It is quite evident that both of these claims can not be true. I think no informed person at home or abroad would blame us for not intervening in affairs which are peculiarly the concern of others to adjust, or when we are asked for help for stating clearly the terms on which we are willing to respond..

“For the United States not to wish Europe to prosper would be not only a selfish, but an entirely unenlightened view. We want the investment of life and money which we have made there to be to their benefit. We should like to have our Government debts all settled, although it is probable that we could better afford to lose them than our debtors could afford not to pay them. Divergent standards of living among nations involve many difficult problems. We intend to preserve our high standards of living and we should like to see all other countries on the same level. With a whole-hearted acceptance of republican institutions, with the opening of opportunity to individual initiative, they are certain to make much progress in that direction.

“It is always plain that Europe and the United States are lacking in mutual understanding. We are prone to think they can do as we can do. We are not interested in their age-old animosities, we have not suffered from centuries of violent hostilities. We do not see how difficult it is for them to displace distrust in each other with faith in each other. On the other hand, they appear to think that we are going to do exactly what they would do if they had our chance. If they would give a little more attention to our history and judge us a little more closely by our own record, and especially find out in what directions we believe our real interests to lie, much which they now appear to find obscure would be quite apparent.

“We want peace not only for the same reason that every other nation wants it, because we believe it to be right, but because war would interfere with our progress. Our interests all over the earth are such that a conflict anywhere would be enormously to our disadvantage. If we had not been in the World War, in spite of some profit we made in exports, whichever side had won, in the end our losses would have been great. We are against aggression and imperialism not only because we believe in local self-government, but because we do not want more territory inhabited by foreign people. Our exclusion of immigration should make that plain. Our outlying possessions, with the exception of the Panama Canal Zone, are not a help to us, but a hindrance. We hold them, not as a profit, but as a duty. We want limitation of armaments for the welfare of humanity. We are not merely seeking our own advantage in this, as we do not need it, or attempting to avoid expense, as we can bear it better than anyone else.

“If we could secure a more complete reciprocity in good will, the final liquidation of the balance of our foreign debts, and such further limitation of armaments as would be commensurate with the treaty renouncing war, our confidence in the effectiveness of any additional efforts on our part to assist in further progress of Europe would be greatly increased.

“As we contemplate the past ten years, there is every reason to be encouraged. It has been a period in which human freedom has been greatly extended, in which the right of self-government has come to be more widely recognized. Strong foundations have been laid for the support of these principles. We should by no means be discouraged because practice lags behind principle. We make progress slowly and over a course which can tolerate no open spaces. It is a long distance from a world that walks by force to a world that walks by faith. The United States has been so placed that it could advance with little interruption along the road of freedom and faith.

“It is befitting that we should pursue our course without exultation, with due humility, and with due gratitude for the important contributions of the more ancient nations which have helped to make possible our present progress and our future hope. The gravest responsibilities that can come to a people in this world have come to us. We must not fail to meet them in accordance with the requirements of conscience and righteousness” — Calvin Coolidge, Excerpt of Address at the Observance of Tenth Anniversary of the Armistice, hosted by the American Legion at the Washington Auditorium in Washington, D. C., 9PM, November 11, 1928.

Thank you to all who have worn the uniform and borne sacrifices in America’s defense of peace!