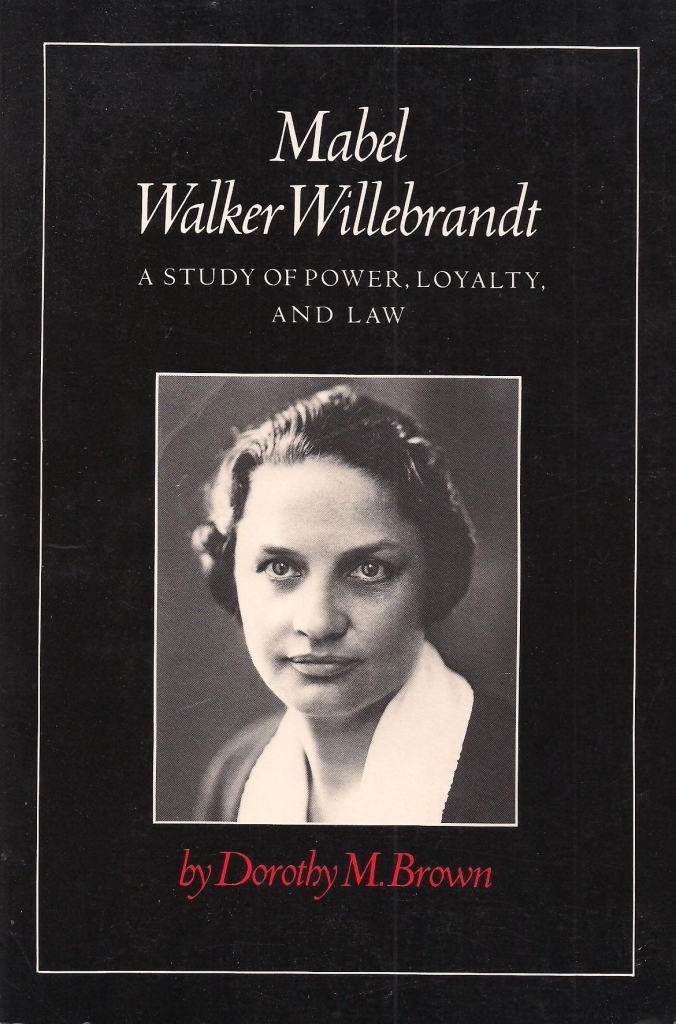

Dr. Dorothy M. Brown, alumna of Notre Dame and former Provost and Professor of History at Georgetown until 2002, has made an impact not only in Catholic higher education for nearly forty years but in the historiography of the 1920s. Dr. Brown has written three books relating to her specialty in the Progressive Era: Mabel Walker Willebrandt being her first work, published in 1984. Three years later she completed American Women in the 1920s: Setting a Course and in 2000, collaborated on The Poor Belong To Us: Catholic Charities and American Welfare.

Coolidge, in this fascinating and definitive biography of Willebrandt, makes a regular appearance, since Mrs. Willebrandt served as Assistant Attorney General, in charge of Prohibition enforcement, during both the Harding and Coolidge years. Born in 1889 on the Kansas prairie, she would remain a Westerner in heart and outlook all her life, even through the trying and dreary years in Washington. Her loyalty, meticulous nature, and determination had great influence on the policy of these administrations and are all brought forward in this fascinating biography. It is quickly realized what an incredible life she lived. Her accomplishments in so many areas of the law and in public service are all the more impressive considering her hearing disability and other obstacles.

It is all the more noteworthy that she was the highest ranking woman in the administration long before it was politically fashionable to name women to important federal posts. Coolidge stood by her even with the collapse of the Harding tenure, and through the upheaval, controversy, and transition under three more Attorneys General. She was ever the faithful and tenacious public servant, helping clean up the Justice Department with Harlan Stone and then to help the work return to proper proportions under John Sargent. It was out of Coolidge’s careful study of issues in the fall of 1923 that he came to collaborate so effectively with Willebrandt. This political partnership ensured the prison reforms she identified, and proposed by President Coolidge, saw completion, shepherding the separate reformatory systems for women at Alderson, young men serving their first sentence at Chillicothe, and the earning program for prisoners at the shoe factory in Leavenworth.

Her progressive politics never lured her away from the Republican Party and she would be one of the most steadfast supporters of Robert A. Taft through the dark days of the 1940s until his final effort ended unsuccessfully in 1952. Even her sympathies for the Progressive candidate in 1924 did not lessen her respect for Coolidge’s integrity and strength of purpose. Nor did it compromise Coolidge’s backing. He defended her even with her efforts to keep the discordant U.S. District Attorneys on task, enforcing Prohibition. While Dr. Brown subscribes to the opinion that Attorney General Stone was “kicked upstairs” to the Supreme Court, we know that Coolidge would not have selected Stone with so self-serving or flippant a reason. Coolidge had nothing to hide and knew Stone was doing exactly what he needed to do after the previous administration had wrought so much harm to law enforcement. While Coolidge never disclosed what he thought of his one Supreme Court nominee in later years, he retained Stone’s regard and friendship. For all that Stone would become, it can be said that he lived up to Coolidge’s intention that judges see above the heads of the parties and decide independently of the particular interests involved. The facts and the law were not to be secondary before predetermined sympathies for one side or the other. It is likely that Willebrandt, who held the highest admiration for Justices Holmes and Stone, would have been the same kind of judge.

Willebrandt’s lifelong desire to become a federal judge never happened, even after the numerous occasions afforded during the Coolidge and Hoover administrations. The patronage rivalry between California’s two U.S. Senators was too unyielding to ever “close the deal” for Willebrandt. Neither was willing to budge on their power to select candidates. We again must respectfully disagree with Dr. Brown that Coolidge was hesitant to name a woman to the bench out of some kind of political chauvinism, for he was the first to name a woman to the federal courts: Genevieve Cline to Customs. His hesitancy had to come from other reasons, foremost being his general commitment to keeping good subordinates in the jobs they do best. He understand it was people like Mabel Willebrandt who were the real reason things got done in any department. Willebrandt’s relationship with Hoover is much less harmonious. After virtually sacrificing herself during the 1928 campaign on his behalf, she never received the kind of appreciative acknowledgment either personally or professionally from him. Even years later, in her last plea that Hoover exercise his influence on Truman to name her to the bench, it seems he did nothing. Of course, the politics at the time were particularly volatile for Truman but her last attempt met with defeat.

Willebrandt (far right) and the Mayer family meeting President Coolidge at the White House, February 3, 1927.

Following her resignation from Hoover’s Justice Department, Willebrandt’s legacy as a superlative advocate at the bar is recounted over the course of some thirty years. She would be instrumental in the development of the California grape and wine industries, an irony not lost on her who had been the #1 enforcement officer of Prohibition. She virtually defined both aviation and radio law in their early development. Her pivotal role as the legal counsel in Hollywood aided many of the names we now know as legends, from Louis B. Mayer to Frank Capra to Clark Gable to many others. Willebrandt would leave her mark everywhere she went. Defending Hollywood from wholesale charges of complicity with Communism, she also substantiated the real threats discovered by Senator McCarthy and defended him when few were brave enough to do so publicly.

Her closing years, full of her legal and political work, continued into the 1960s. She never trusted Nixon and found him to be a dangerous prospect for the White House in 1960 as well as the California Governor’s mansion in 1962. Ultimately exhausted by her work, she finally hung up her law practice and stepped into a reluctant retirement which even her lifelong rebelliousness found odious. She died of lung cancer on April 6, 1963, just short of her 74th birthday. She, like Coolidge friend Frank W. Stearns, would come to Catholicism during the 1930s after a faith that started from childhood, passed through Christian Science but never abandoned her favorite passage, II Timothy 1:7: “For God has not given us a spirit of fear, but of power, and love, and sound mind.” Dr. Brown has accomplished a great task in retelling her life, especially when she steps out of the limelight upon leaving government service in 1931. To reapply a phrase from her friend Frank Capra, she really had a wonderful life. With all her triumphs and also failures, she remains one from which to learn and with qualities to admire even now.