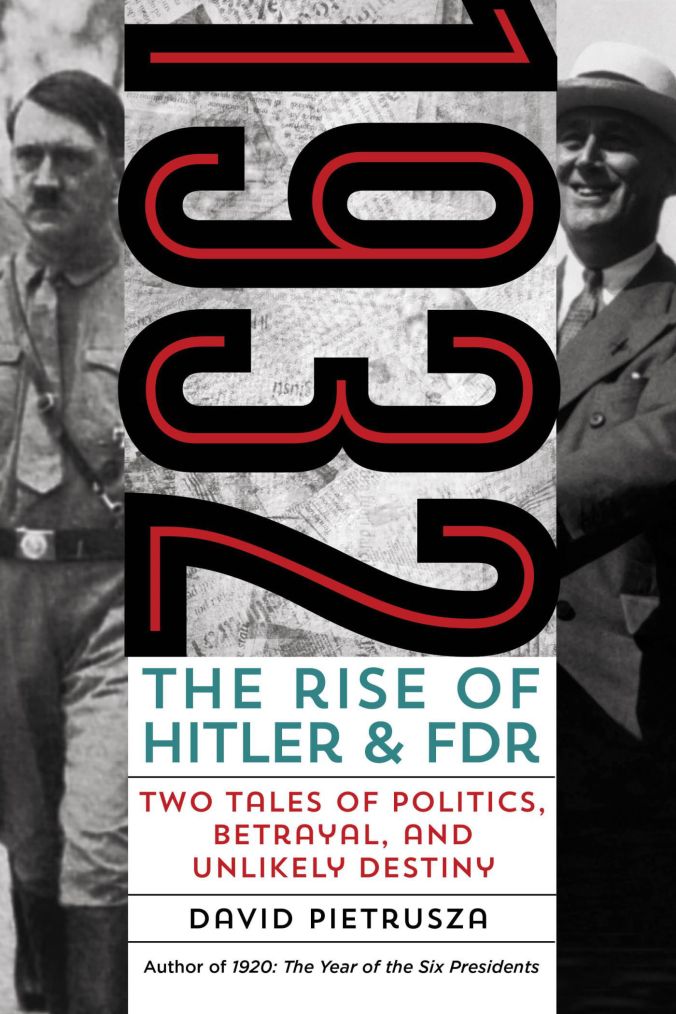

Coming out October of last year, 1932: The Rise of Hitler and FDR – Two Tales of Politics, Betrayal, and Unlikely Destiny complements the growing collection of electoral histories by Coolidge scholar and meticulous historian David Pietrusza. Between the authoring of his latest book and his previous titles, 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents, 1948: Harry Truman’s Improbable Victory and the Year that Transformed America, and 1960 – LBJ vs. JFK vs. Nixon: The Epic Campaign That Forged Three Presidencies, Mr. Pietrusza somehow found time to complete three other collections of documents and historical materials on Calvin Coolidge, Silent Cal’s Almanack, Calvin Coolidge on the Founders, and Calvin Coolidge: A Documentary Biography. He is known around the country not only for his prolific body of writing but also for his frequent participation in radio and TV programs featuring the various historical subjects with which he stands preeminent conversant.

Coolidge, while not the leading “actor” in Pietrusza’s latest book, serves an important role. We first encounter him characteristically at his desk, setting the sharpest contrast to the man who would become his successor, Herbert Hoover, then serving as Secretary of Commerce. This marked difference in personality, ability, and approach continues to be woven together in a narrative that is both fascinating and original. Pietrusza alternates each chapter between the stirring rise of FDR in America and the halting, even sputtering, climb of Hitler in Germany. In both instances we are reminded that history is anything but foregone or predetermined. Nothing that happened had to happen.

Meanwhile, we see the dramatic free-fall of one lauded as the “Great Engineer,” who had won the greatest electoral victory a short four years before by promising to continue the policies of his predecessor, Mr. Coolidge. Time would quickly unravel this pledge and Hoover’s political inexperience would lead to historic defeat, inflicting a brooding degree of self-doubt which, some argue, still haunts the GOP as a party. Having worked his way up in the mining industry, Hoover saw his private sector efforts crowned with his first million before he was thirty, but he had only known public life as an appointee or bureaucrat by 1928. Living abroad for much of his early life, he never mastered either the wisdom of delegation as an executive or the political skill essential in America’s system of co-equal authority. He never had to run for office until the Presidency. In these fundamentals he could not be more different from the politically experienced, shrewd but humble Calvin Coolidge. Becoming his own worst enemy, Hoover self-destructs and, unwittingly, paves the way for FDR’s landslide victory in November 1932. Across the pond, Germany collapses from within, each painful step of the way leading to Hitler being given the chancellorship he so covets.

Coolidge, now in retirement, watched all these developments with growing concern, knowing that national leadership now fell to other men. Resisting every push by Hoover to take a more active part in the functions that properly belonged to the President (such as dedicating the Olympics in Los Angeles that year), Coolidge finally agreed to speak on behalf of his party, whose prospects appeared dismal indeed that autumn. A loyal Republican, Cal not only spoke (despite his struggling voice) but he wrote, delivered one final message from his home in Northampton just before election day, and actually voted with Mrs. Coolidge early the next morning in their old Ward 4. Coolidge’s address at Madison Square Garden put FDR on defense, forcing the Democrat to explain his deliberately vague position on such matters as the Veteran’s Bonus. Cal’s reluctant participation, completed with what he saw as his solemn duty to vote, was more than many did that year as FDR swept every section of the country but New England. By January, FDR would be finalizing Cabinet appointments at the Coolidge funeral through his proxies and talking increasingly of dictatorial powers. It was indeed a different world than Cal had known just a few short years before, a world where America and Europe were tragically poised to begin a decade of preparation for a second global war.

Pietrusza infuses what could be a tedious, even dry, narrative (especially explaining the Germany party system) with a vivid array of sub-plots and intriguing facts. 1932 is an essential study of the year that ushered in drastic change to our political identity and cultural makeup. Also, however, it carries an implicit warning of where individuals and nations can go when the desperation for any perceived escape (however superficial) from political, social or personal disaster relinquishes unaccountable power to nearly anyone ambitious enough to promise total rescue. In their acute distress many turn to those least qualified to lead them forth into the assurance that something different means something better. As Pietrusza reminds us, history does not bear out that often illusory hope.