Hitting bookshelves just before President’s Day last month, historian and prolific author Brion McClanahan has taken up the task of assessing the flawed way we view our Presidents. Accomplishing this, especially in the midst of a Presidential campaign, has no shortage of importance. He underscores how this is much more than an intellectual exercise, it has and will continue to define what kind of people we are and what sort of country we intend to be.

Taking up where Steven F. Hayward began in his Politically Incorrect Guide to the Presidents: From Wilson to Obama, McClanahan argues that the only legitimate means of judging our Presidents must be the fidelity they had or did not have to their oath of office. Did they keep that sacred promise to “faithfully execute the Office” and “to the best of their ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States”?

McClanahan surveys the nine biggest failures, most of whom we have been taught belong among the greatest of the great. The opposite actually holds true when the Oath of Office is the gauge of success. The author, turning the premise on its head, shows how activist Presidents have been some of our worst. This carries the whole notion of “greatness” back to substantive ground by cutting through much of the emotionally-based and often politically Left-wing favoritism that usually dominates Presidential rankings. However, McClanahan does not end his Presidential primer on a sour note. He offers four successful examples among our Chief Executives, including Calvin Coolidge. Knowing how sparse the field of constitutionally principled leaders is in the twentieth century, Calvin Coolidge stands as the tallest and strongest demonstration of what the Founders meant for the President’s role in our Republic.

The author dusts off the years of accumulated misunderstanding and even deliberate misrepresentation of “Silent Cal.” McClanahan corrects the record, showing that Coolidge exerted a powerful check on the deviations from legitimate constitutional authority over both the Executive and Legislative Branches. He was not only his own man but was criticized at the time for using too much executive power when he was merely restoring the balance between states and the federal government as well as between the President and Congress. He had “backbone” and was fearless in the exercise of his constitutional obligations. While his vetoes may not have always possessed the rhetorical punch of Jackson or Tyler, they essentially halted attempt after attempt by Congress to legislate illegitimate appropriations and government expansion. Coolidge was the most effective channel of Jefferson and Washington in both the defense of federalism – the authority of the states and local government – and in the exercise of foreign policy.

Coolidge, often blamed for the depression and rise of totalitarianism in the 1930s, deserves full exoneration. They both came at a time that was enthusiastically running away from the very leadership approach and economic policy of Coolidge. Hoover and FDR were diametric opposites to Cal. Had Coolidge been President in the 30s, McClanahan reminds us, the depression would not have become “Great,” but would have seen a much quickery by restraining taxes and spending, like was done in 1921.

As for the rise of totalitarianism, it was Coolidge’s conscientious neutrality, crafted with the Senate’s “advice and consent” of the Kellogg-Briand Pact (not unilaterally approved like some Presidents do) that “kept the United States out of the broiling mess” that had been created by intervention under Wilson in the first place. National responsibility to other lands and peoples was not an inexhaustible or unlimited resource, Coolidge believed. America would be ready to help and serve but “We cannot make over the people of Europe. We must help them as they are, if we are to help them at all.”

Such a policy did not deny evil exists in the world but recognized we cannot fight everyone’s battles for them nor is it our place to save the world from its own responsibilities. This is a powerful statement against constant and seemingly unending intervention, a debate that is most timely today. Coolidge would not have been suckered in by the flimsy argument that American identity is somehow on the line if we do not open-endedly commit money, resources, or people to the plights of other nations. This is not an either-or policy, refusing any help at all if we do not accept the entire load, for we generously assisted Japan after earthquakes struck there in 1923. We supported the privately-funded rescue of the Armenian orphans fleeing the genocide of their parents. Rather than randomly carve up the world as the Allies did at Versailles, we appealed to objective rules of law in arbitrating international differences. We were on hand at the League of Nations for every important and pivotal decision of the 1920s but refused to obligate ourselves and subordinate our sovereignty to assume the burdens each nation must inevitably carry. We would not be able to do much good for anyone if we stretched that impossibly thin. Cal knew this and warned against it just as President Washington did.

McClanahan has much to praise about Coolidge but he also addresses the one constitutional inconsistency of his Presidency: signing the largest flood relief measures ever approved up to that point. It exceeded the bounds of the Commerce Clause and set the precedent for even more flagrant abuse by FDR years later. There is merit to the author’s argument. Coolidge, directly involved in paring down the ridiculous expense of the original bill, could have kept fighting and even veto the legislation. The result was far less extravagant than it started out to be but Coolidge concluded it was the best that could be obtained. Starting over would not ensure a more economical result, it would (if anything) reopen and multiply the petitions for public money. Nonetheless, Coolidge could have vetoed the measure and let Congress take responsibility for the result. This is why the Presidency was not supposed to incorporate legislative powers.

Finally, as the survey of Coolidge concludes, McClanahan cites the critic H. L. Mencken (a man who was no friend of Cal) with a rare moment of genuine praise for #30:

“We suffer most when the White House busts with ideas. With a World Saver [Wilson] preceding him (I count out Harding as a mere hallucination) and a Wonder Boy [Hoover] following him, [Coolidge] begins to seem, in retrospect, an extremely comfortable and even praiseworthy citizen…If the day ever comes when Jefferson’s warnings are heeded at last, and we reduce government to its simplest terms, it may very well happen that Cal’s bones now resting inconspicuously in the Vermont granite will come to be revered as those of a man who really did the nation some service.”

Cal was much more the common man than Truman and an even more consistently principled conservative than Reagan. McClanahan hails him as the last President, and the only one of the twentieth century to emulate, who genuinely believed in the Constitution as it was ratified. The author closes with a fascinating set of proposed amendments to our Constitution that would finally start restraining the powers that have grown around and over the Office as it was supposed to be. He notes that even could faithful, old Cal be resurrected and serve again, we would need these changes to our Charter. Sadly, McClanahan believes, we have stepped onto a path that no simple change of personnel will alter. The Constitution must be revised and reasserted. Perhaps Coolidge would agree. After all, he always was a firm believer in the importance of the amendment process to effect change. He condemned the notion that such was the province of either judicial legislators or executive regulators.

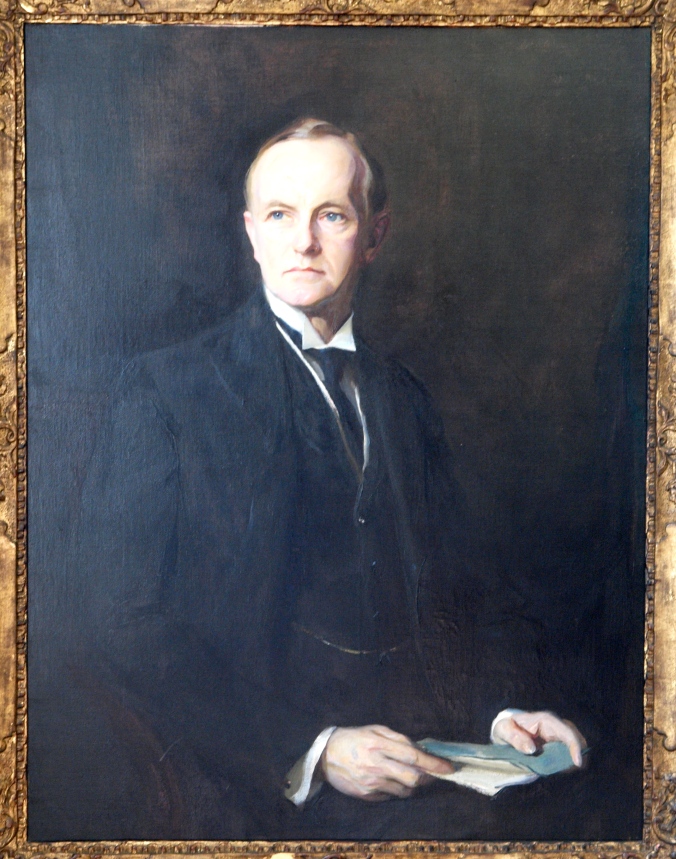

President Calvin Coolidge, portrait by Philip A. deLaszlo, 1926.