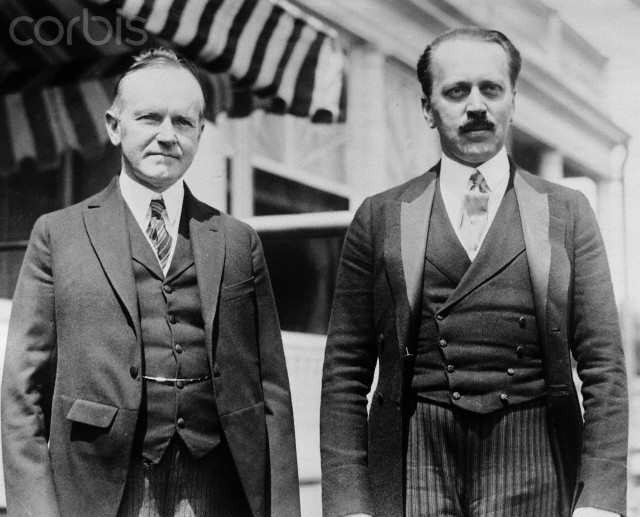

President Coolidge with Count Alex Skrzynski, Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs, Swampscott, Massachusetts, July 17, 1925. Courtesy of Corbis.

Much has been brought to the forefront of the Presidential campaign this week about handling disagreement, responding to protesters, and the healthy respect and regard that both sides of each issue must show in civil debate.

We do not, and never will, completely agree on all matters. If we did, we would enter, as Calvin Coolidge expressed it, “a state of equilibrium closely akin to an intellectual and spiritual paralysis.” At the same time, just because we do not see things eye to eye – a fact of our entire history – this does not give us permission to encourage violent reaction against those we find on the “other side.” This applies with the same force to those on one side who proudly mock the obedience to law and order while those on the other side hold the decency of treating others as we would be treated with equal contempt. Both are guilty even if you are a Presidential candidate who praises the good old days when brawling and “roughing up” were supposedly acceptable. He, while characteristically denying his influence, has effectively been giving permission to violently remove dissenters from his rallies rather than exemplify respect to those with whom we disagree. The criminal can be found on each side and should be held equally accountable under the law. Both are violating the freedoms of the First Amendment. Both are guilty whether you throw the punch or receive it, whether you are an opposition activist seeking to disrupt and destroy or a reckless supporter who perpetuates “us” versus “them,” with a lack of control. Neither is a victim when both have abandoned the American ideals of mutual respect and toleration, of forbearance and self-control.

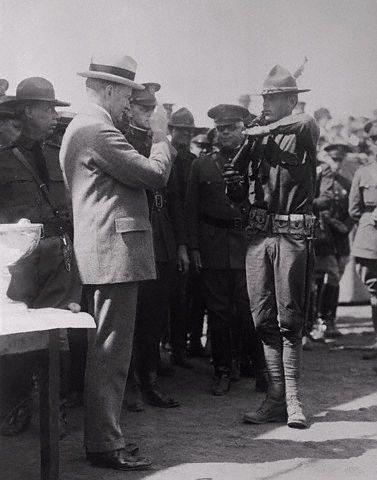

President Coolidge returning the salute of his son, cadet John Coolidge, at Camp Devens, August 30, 1925.

Coolidge, in a speech commended at the time for its courage and resolve, went to one of the “ground zeros” of racial and political discord of the 1920s, the city of Omaha, Nebraska, which had experienced one of the worst riots in 1919. He went not to investigate those insufficiently “down with the struggle” nor to embroil Washington in fixing America’s racism. He went to heal, to bring Americans back together, and make the case for the nation’s exceptional ideals, ideals that unite and bring peace.

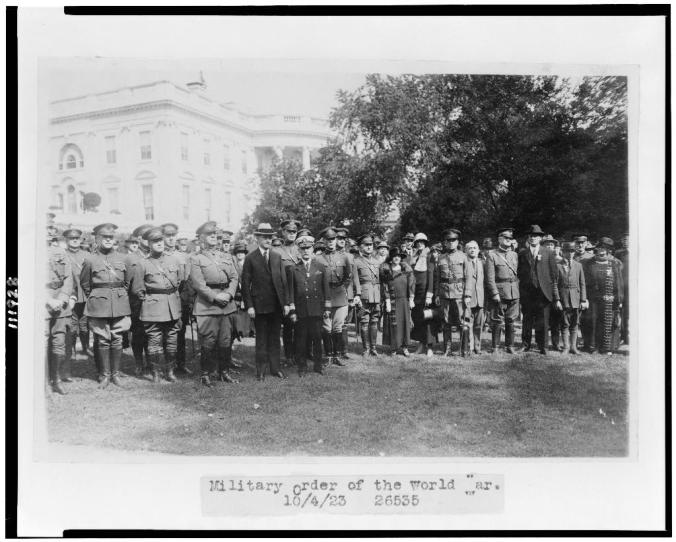

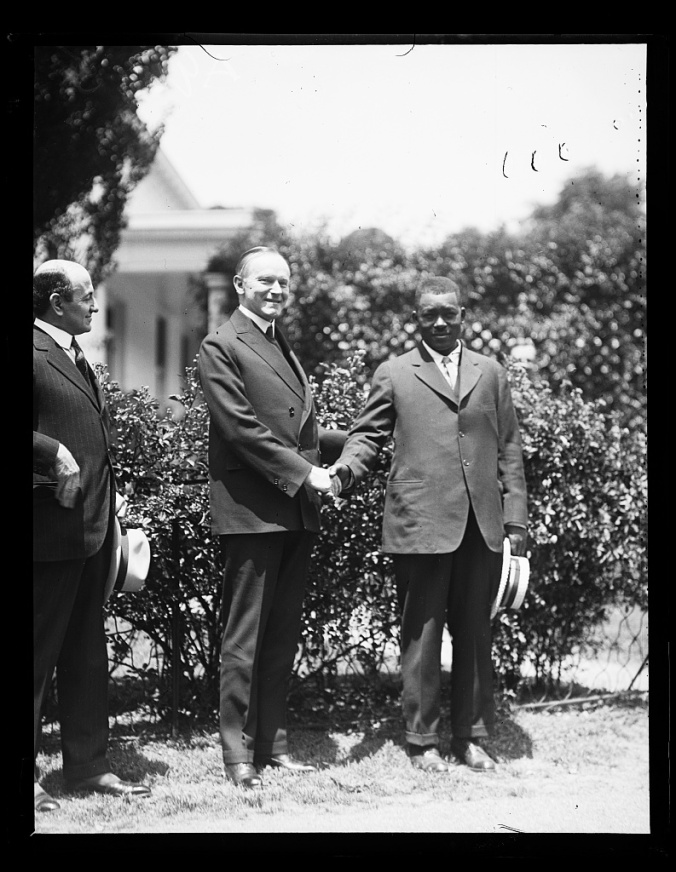

President Coolidge, two years before, at the White House

Coolidge’s message, addressing those of all backgrounds who had served in the recent World War, was also broadcast across the country. In effect, it was something everyone needed to hear. It is likewise, something we need to hear again.

Part of the illustrious 369th, “Harlem Hellfighters,” among many whom President Coolidge had in mind during this speech.

Turning to the racial and political hostility his audience knew, he said,

“We need to consider what attitude of the public mind it is necessary to cultivate in order that a mixed population like our own may dwell together more harmoniously and the family of nations reach a better state of understanding. You who have been in the service know how absolutely necessary it is in a military organization that the individual subordinate some part of his personality for the general good. That is the one great lesson which results from the training of a soldier. Whoever has been taught that lesson in camp and field is thereafter the better equipped to appreciate that it is equally applicable in other departments of life. It is necessary in the home, in industry and commerce, in scientific and intellectual development. At the foundation of every strong and mature character we find this trait, which is best described as being subject to discipline. The essence of it is toleration. It is toleration in the broadest and most inclusive sense, a liberality of mind, which gives to the opinions and judgements of others the same generous consideration that it asks for its own, and which is moved by the spirit of the philosopher who declared that ‘To know all is to forgive all.’ It may not be given to finite beings to attain that ideal, but it is none the less one toward which we should strive.”

He continued,

“One of the most natural reactions during the war was intolerance. But the inevitable disregard for the opinions and feelings of minorities is none the less a disturbing product of war psychology. The slow and difficult advances which tolerance and liberalism have made through long periods of development are dissipated almost in a night when the necessary war-time habits of thought hold the minds of the people. The necessity for a common purpose and a united intellectual front becomes paramount to everything else. But when the need for such a solidarity is past there should be a quick and generous readiness to revert to the old and normal habits of thought. There should be an intellectual demobilization as well as a military demobilization. Progress depends very largely on the encouragement of variety. Whatever tends to standardize the community, to establish fixed and rigid modes of thought, tends to fossilize society. If we all believed the same thing and thought the same thoughts and applied the same valuations to all the occurrences about us, we should reach a state of equilibrium closely akin to an intellectual and spiritual paralysis. It is the ferment of ideas, the clash of disagreeing judgments, the privilege of the individual to develop his own thoughts and shape his own character, that makes progress possible. It is not possible to learn much from those who uniformly agree with us. But many useful things are learned from those who disagree with us; and even when we can gain nothing our differences are likely to do us no harm.”

Coolidge warned,

“In this period of after-war rigidity, suspicion, and intolerance our own country has not been exempt from unfortunate experiences. Thanks to our comparative isolation, we have known less of the international frictions and rivalries than some other countries less fortunately situated. But among some of the varying racial, religious, and social groups of our people there have been manifestations of an intolerance of opinion, a narrowness of outlook, a fixity of judgment, against which we may well be warned. It is not easy to conceive of anything that would be more unfortunate in a community based upon the ideals of which Americans boast than any considerable development of intolerance as regards religion. To a great extent this country owes its beginnings to the determination of our hardy ancestors to maintain complete freedom in religion. Instead of a state church we have decreed that every citizen shall be free to follow the dictates of his own conscience as to his religious beliefs and affiliations. Under that guaranty we have erected a system which certainly is justified by its fruits. Under no other could we have dared to invite the peoples of all countries and creeds to come here and unite with us in creating the State of which we are all citizens.

“But having invited them here, having accepted their great and varied contributions to the building of the Nation, it is for us to maintain in all good faith those liberal institutions and traditions which have been so productive of good. The bringing together of all these different national, racial, religious, and cultural elements has made our country a kind of composite of the rest of the world, and we can render no greater service than by demonstrating the possibility of harmonious cooperation among so many various groups. Every one of them has something characteristic and significant of great value to cast into the common fund of our material, intellectual, and spiritual resources.”

Americans of all backgrounds had served side by side in the late war, proving that an appeal to our better selves, a living up to higher ideals, was possible. It was just as possible to achieve that colorblind, mutually respectful, and united life together, around our shared ideals, with the war over. Coolidge kept at it, explaining clearly,

“We must not, in times of peace, permit ourselves to lose any part from this structure of patriotic unity. I make no plea for leniency toward those who are criminal or vicious, are open enemies of society and are not prepared to accept the true standards of our citizenship. By tolerance I do not mean indifference to evil. I mean respect for different kinds of good. Whether one traces his Americanism back three centuries to the Mayflower, or three years of the steerage, is not half so important as whether his Americanism of to-day is real and genuine. No matter by what various crafts we came here, we are all now in the same boat. You men constituted the crew of our ‘Ship of State’ during her passage through the roughest waters. You made up the watch and held the danger posts when the storm was fiercest. You brought her safely and triumphantly into port. Out of that experience you have learned the lessons of discipline, tolerance, respect for authority, and regard for the basic manhood of your neighbor. You bore aloft a standard of patriotic conduct and civic integrity to which all could repair. Such a standard, with a like common appeal, must be upheld just as firmly and unitedly now in time of peace. Among citizens honestly devoted to the maintenance of that standard there need be small concern about differences of individual opinion in other regards. Granting first the essentials of loyalty to our country and to our fundamental institutions, we may not only overlook but we may encourage differences of opinion as to other things. For differences of this kind will certainly be elements of strength rather than of weakness. They will give variety to our tastes and interests. They will broaden our vision, strengthen our understanding, encourage the true humanities, and enrich our whole mode and conception of life. I recognize the full and complete necessity of one hundred per cent Americanism, but one hundred per cent Americanism may be made up of many various elements.

“If we are to have that harmony and tranquillity, that union of spirit which is the foundation of real national genius and national progress, we must all realize that there are true Americans who did not happen to be born in our section of the country, who do not attend our place of religious worship, who are not of our racial stock, or who are not proficient in our language. If we are to create on this continent a free Republic and an enlightened civilization that will be capable of reflecting the true greatness and glory of mankind, it will be necessary to regard these differences as accidental and unessential. We shall have to look beyond the outward manifestations of race and creed. Divine Providence has not bestowed upon any race a monopoly of patriotism and character.”

This principle, this attitude of mind, applied just as forcefully to nations as it does to individuals. The debate how to put “America first” was as spirited and intense then as now. Coolidge outlines the path that will not take us forward and describes the course that will,

“It can not be done by the cultivation of national bigotry, arrogance, or selfishness. Hatreds, jealousies, and suspicions will not be productive of any benefits in this direction. Here again we must apply the rule of toleration. Because there are other peoples whose ways are not our ways, and whose thoughts are not our thoughts, we are not warranted in drawing the conclusion that they are adding nothing to the sum of civilization. We can make little contribution to the welfare of humanity on the theory that we are a superior people and all others are an inferior people. We do not need to be too loud in the assertion of our own righteousness. It is true that we live under most favorable circumstances. But before we come to the final and irrevocable decision that we are better than everybody else we need to consider what we might do if we had their provocations and their difficulties. We are not likely to improve our own condition or help humanity very much until we come to the sympathetic understanding that human nature is about the same everywhere, that it is rather evenly distributed over the surface of the earth, and that we are all united in a common brotherhood. We can only make America first in the true sense which that means by cultivating a spirit of friendship and good will, by the exercise of the virtues of patience and forbearance, by being ‘plenteous in mercy,’ and through progress at home and helpfulness abroad standing as an example of real service to humanity.”

The President being pinned by Mrs. Coolidge with the first Red Cross Button of that year’s annual drive, Washington, October 29, 1925.

Coolidge drives the point home, declaring,

“It is for these reasons that it seems clear that the results of the war will be lost and we shall only be entering a period of preparation for another conflict unless we can demobilize the racial antagonisms, fears, hatreds, and suspicions, and create an attitude of toleration in the public mind of the peoples of the earth. If our country is to have any position of leadership, I trust it may be in that direction, and I believe that the place where it should begin is at home. Let us cast off our hatreds…If the world has made any progress, it has been the result of the development of other ideals. If we are to maintain and perfect our own civilization, if we are to be of any benefit to the rest of mankind, we must turn aside from the thoughts of destruction and cultivate the thoughts of construction. We can not place our main reliance upon material forces. We must reaffirm and reinforce our ancient faith in truth and justice, in charitableness and tolerance. We must make our supreme commitment to the everlasting spiritual forces of life. We must mobilize the conscience of mankind.

“Your gatherings are a living testimony of a determination to support these principles. It would be impossible to come into this presence, which is a symbol of more than three hundred years of our advancing civilization, which represents to such a degree the hope of our consecrated living and the prayers of our hallowed dead, without a firmer conviction of the deep and abiding purpose of our country to live in accordance with this vision. There have been and will be lapses and discouragement, surface storms and disturbances. The shallows will murmur, but the deep is still. We shall be made aware of the boisterous and turbulent forces of evil about us seeking the things which are temporal. But we shall also be made aware of the still small voice arising from the fireside of every devoted home in the land seeking the things which are eternal. To such a country, to such a cause, the American Legion has dedicated itself. Upon this rock you stand for the service of humanity. Against it no power can prevail.”

President Coolidge knew that the “anger of man” never yielded the righteousness of God (James 1:19-20; Titus 3:10-11), that befriending the angry and violent would merely result in learning those ways and ensnaring the soul (Proverbs 22:24-25; 29:22). He knew this happens to nations as well as individuals. This is what compelled him to speak, to appeal to greater principles, to champion the truth. For, as is written, “If it is possible, so much as it depends on you, live peaceably with all men”(Romans 12:16-21), and again, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God”(Matthew 5:9).

Pingback: On Confusing Proximity with Causation | The Importance of the Obvious