President Coolidge, sitting in the automobile (foreground), moving through the streets of Havana toward the Presidential Palace, January 15, 1928.

President Calvin Coolidge finds his name in the news this week but like much of the media’s focus these days, it is with a barely concealed contempt. The current President, as we all know, is on another leg of the “Apologize for America” tour, starting with the first visit to Cuba since Coolidge’s in 1928. While much of the infantile and ridiculous behavior on the part of participants during both visits has been reported, the worst culprits eighty-eight years ago were the United States press corps, whose litany of pranks and permissive conduct did little to elevate the reputation of the Fourth Estate. This time, it is the President of the United States himself who impugns the responsibility he carries and mocks its importance.

Not so in 1928. President Coolidge was everything one would expect a serious leader of world influence to be. He knew the burden of the Presidency’s moral weight was felt around the globe for better or worse. He would not use that authority cavalierly. He exemplified the sense of decorum and mature discretion that is a universe away from the current occupant’s indifferent mindset. Coolidge understood what happens when leaders do not furnish the moral integrity back of the responsibility. He knew the vacuum it creates will not raise nations or individuals to strive for higher ideals. He knew the power of leadership is the power to set a higher tone for what is right, to condemn impropriety and embody standards befitting our ideals. That code of conduct was known and felt keenly even by President Machado of Cuba before Coolidge’s arrival. Keep in mind, Prohibition was the law of the land back then in America.

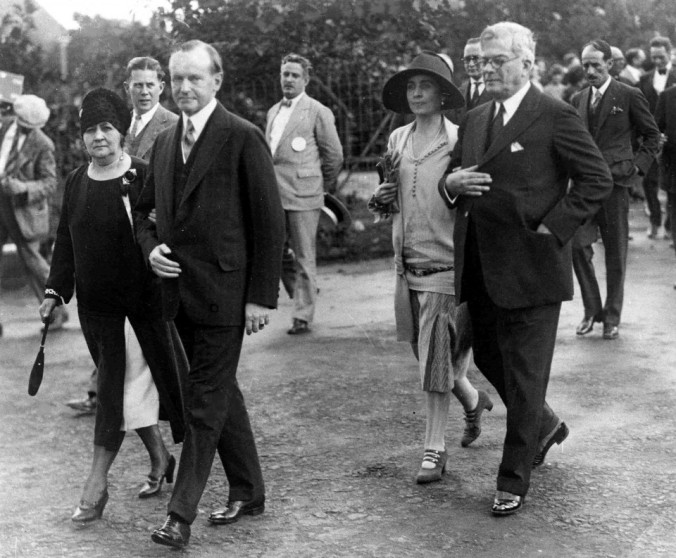

President Coolidge and Cuban President Gerardo Machado

When leaders do not demonstrate the strength of character requisite or fail to demand nothing less than the rule of law, why should anyone else expect that rule not to relax or disappear entirely from whole segments of society? We saw it with Bill Clinton and the permissiveness that begets permissiveness. We see it now even when we cannot fully quantify it. Coolidge knew America was not perfect but he knew it adhered to principles worth preserving not apologizing for, a good deserving of respect, and duties summoning our “better selves” to live up to them. We would never arrive at them but through reaching for them we elevate our moral character and inspire the same in others. He took a justified pride in what the Americas, North and South, had done with the opportunities given them to build on something ennobling, ideals greater than what had been before them in the Old World.

Machado required the removal of Cal’s portrait from alcoholic establishments across the island before the Presidential party came ashore. That simple act, while not exactly corresponding to the very clear guarantees of the largely republican form of government that existed under the 1901 Cuban constitution in force at the time, tells us something else. Moral leadership influences other leaders. By expecting more of himself than a strictly legal adherence to the Constitution and rule of law – which did not transcend United States’ jurisdiction – Coolidge was adhering to something more than the letter of the law, he was practicing his obligation to be a moral example. To most of those who accompanied him to Cuba, his unimpeachable character was respected and followed. But, as correspondent Beverly Smith would disclose thirty years later, some took full advantage of when the President was not looking. It illustrated the timeless tenet of human nature, “when the cat’s away, the mice will play.” In this case, it said more about the mice than any dereliction on the part of the cat. At the same time nearly everyone knew the mistake that was Prohibition.

USS Texas entering Havana’s harbor, January 15, 1928. Notice the crowds awaiting the Presidential party.

When word came down that the Presidential party would not be checked by customs upon returning to the United States, it did encourage many to find inventive ways of hiding alcohol among one’s luggage. It teaches again, especially concerning unpopular laws, when enforcement is not upheld consistently, standards slip very quickly, even under the best of circumstances. The eagerness to dismiss Coolidge exposes yet again the double standard of the press on a very similar, but even more dangerous, oversight. It is the task of enforcing the law against radical Islamic terror cells across this country. Some are all too ready to dismiss the duty to enforce the law as an impossible and unrealistic task. They say the same about immigration enforcement. It escapes notice that patrolling neighborhoods and working alongside communities to proactively prevent these cells is not only doable but is already on the books to be done.

It is none less than the President who sets the tone for good or bad. When he cannot even bring himself to utter the words, “radical Islam,” at the same time dismissing the attack in Brussels as much ado about nothing, attending first a baseball game in Cuba and then stopping to Tango in Argentina, he is deliberately showing a deficit of leadership. Combine this with all the rest of what has transpired these last seven years, including the use of the IRS to target political enemies, the use of the Justice Department to take sides against the most basic enforcement of our laws from New York to Ferguson to San Francisco, and the pervasive belief that Hillary Clinton will never see indictment, we are witnessing a President engaged in far more than well-meaning oversight. It is a wholesale refusal to protect and defend the rule of law, the fundamental glue that keeps society from total collapse.

Coolidge knew how imperative the rule of law had to be when, as Governor of Massachusetts, he resisted the reinstatement of the Boston police officers who left their posts and the city to the opportunists of 1919. He rightly confronted it and won for law and order, the equal application of it upon all. As President, he maintained that standard. The exceptions, like the exemption from customs in 1928, took place in spite of the high expectations he set not because of them. That is the vast difference between a President who reveres the rule of law and one who loathes the very concept and actively works against it.

President Coolidge escorting Elvira Machado Nodal, the wife of the Cuban President, who is directly behind Cal, escorting Mrs. Coolidge.

Another favorite criticism of President Coolidge floating around this week is his supposed failure in foreign policy. What failure, it must be asked, since no one can seriously expect that “international bureaucracy” would have made any part of the Kellogg-Briand Treaty more effective? Coolidge himself made plain for years that any international agreement would be mere parchment without the will of each nation’s people behind it. The power of any treaty only ever rests on the heart and moral power of a nation’s people. Peace will only ever come to those who are first peaceful, those who cherish peace. The warlike and violent-spirited will not avoid war. If, however, a new mindset is adopted by both sides to aspire toward and commit publicly to reconciliation of differences without resort to force when reason should prevail, that is a solemn promise and as binding an obligation as any agreement can hope to be. The faithlessness to that pledge before God and man is not the fault of men like Coolidge who appealed to justified ideals, it is the fault of those who broke the compact first in their hearts, rationalized it in their minds, and then betrayed it in their actions years later.

Was is astounding is not that the Kellogg-Briand Pact reveals some childish naivete in Cal’s generation but rather the arrogant presumption that our generation is so much more sophisticated, wise, and visionary. It upstages the ill-founded confidence that agreements with Iran and Cuba will be self-policed and restorative of peace without any of the ideals that ensured Kellogg-Briand, which actually kept the West out of war for another decade, succeeded as well as it did. Blaming Coolidge is like blaming George Washington for his supposedly blind faith that the Jay Treaty would be honored by all parties concerned in Britain and the United States. Both men appealed to higher principles for nations to do what is right. Our generation expects nothing and thus will get nothing in return.

The credit that is grudgingly granted to President Coolidge’s administration on what, in a few years, would be named the “Good Neighbor Policy,” also deserves consideration here. The seeds for bringing the United States back from the incessant intervention in the internal affairs of other nations under TR and Wilson were sown by the Coolidge White House. It was years in the making, not merely thrown together in the last few months of Cal’s Era. He had been outlining the basis for it as Vice President and as Harding’s successor long before Cuba. His speeches before Johns Hopkins University in February 1922 and later the Associated Press in April 1924 and messages to Congress make this clear. Coolidge was deliberately stepping away from the entangling of American sovereignty over the New World as well.

The days when American diplomats would demand something like the Platt Amendment to the Cuban Congress under Teddy Roosevelt were numbered with the arrival of Coolidge. He remained as good as his word, however, when he declared that the United States stood ready to help, as when the Nicaraguan government requested assistance. Coolidge dispatched the Marines to support the government there in the reestablishment of order and with, Ambassador Stimson, to learn the facts from all sides and support an equitable and constitutional resolution by the Nicaraguans themselves. Through it all, Americans were not there to occupy territory and impose outcomes but to aid a sister Republic against those who would overturn it. It is important to note that regime change was not a policy of the Coolidge administration. This adhered to Cal’s conviction that every nation must work out the burdens of freedom and self-government on its own. He continued that theme in Havana, declaring to the whole assembly of Pan-American republics,

“We have put our confidence in the ultimate wisdom of the people. We believe we can rely on their intelligence, their honesty, and their character. We are thoroughly committed to the principle that they are better fitted to govern themselves than anyone else is to govern them. We do not claim immediate perfection. But we do expect continual progress. Our history reveals that in such expectation we have not been disappointed. It is better for the people to make their own mistakes than to have some one else make their mistakes for them.”

Coolidge would never apologize for the deeds of the distant past, he would actually lead off with the glorious potential made possible for liberty and the rule of law with the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the New World. Coolidge had enough perspective and maturity to see that the wrongs of that distant past were in the past between generations long gone. Guilt for them belonged to no one yet living. At the same time, his generation still labored under the cloud of war between Spain and the United States in 1898. That was different. It was the President’s role to take the lead and champion reconciliation. Coolidge did exactly that, dropping anchor in the USS Texas near the site where the USS Maine exploded in Havana harbor, symbolizing the importance of putting the past behind everyone involved.

Coolidge approached the nations of Latin America not as superiors to bow before nor as inferiors to quash but as equals, appealing to a commitment to political freedom, economic opportunity, and constitutional government. The freedoms enshrined in the 1901 Constitution drafted by the Cuban Congress were pledges to its people. All the nations gathered there had begun on that same path as republics and each nation, for the good of its own people and a shared obligation to its New World neighbors, would be responsible for keeping to it. President Machado, for all that he would do, good and bad, still held to the constitutional procedures of amendment and separation of powers because of America’s influence.

The objective was not to place America in the role of international policeman or global kingmaker, choosing who is fit to lead other nations. That remained a decision to be worked out through “public opinion at the ballot box” in each republic. Cuba had come far in a mere thirty years, as Coolidge would observe in Havana. America could afford a patience and understanding commensurate with its strength. It would, as all nations should, insist on its sovereignty, but not merely project power over the slightest offense abroad because it could. America would exemplify a mature sense of proportion, a longsuffering to the growing pains of younger republics (when done in good faith), and a readiness to show good will to everyone prepared to meet their obligations on the world stage. It would not pick winners and losers but it would also not reward lawless and irresponsible regimes like Lenin’s Russia or revolutionary Mexico. America, under Coolidge, embodied the precept that it would serve not demand service, extend friendship to all but not subordinate its decisions to the interests of others. To be at peace it would demonstrate peacefulness. To remain independent it would uphold its sovereignty.

When the FDR administration, on the other hand, prioritized regime change, it opened a series of violent reactions that placed General Batista in dictatorship, departed from the republican model and constitution for a European-style socialism, and paved the way for Castro’s rise in 1959. It was not very different from another disastrous exercise in regime change when the current administration backed away from Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and toppled Muammar Qaddafi in Libya, paving the way for Benghazi and the rise of ISIS. Under FDR, being “Good Neighbors” actually reasserted American intervention in the old way of Woodrow Wilson rather than the principled policy of national independence practiced by Calvin Coolidge. In this way, Cal was a much more consistent and reliable proponent of the “Good Neighbor” principle. He would have avoided the litany of terrible consequences that always attend American attempts to dismantle and rebuild other nations.

This is all the more evident when brought together with the rest of Coolidge’s actions in foreign policy regarding this hemisphere. Coolidge’s readiness to withdraw the Marines from all the sites Wilson had deployed them, while not perfectly orchestrated, did send the signal that Cal was serious about each nation’s standing on their own two feet as sovereign peoples. Coolidge’s handling of the Mexican situation through Ambassador Morrow, the request for help in Nicaragua supplied by Ambassador Stimson, the commission of Charles Lindbergh and the Pan-American Goodwill Flight throughout Central and South America, and the issuance of what would likely be dubbed today the “Coolidge Doctrine” in J. Rueben Clark’s memorandum all demonstrate the seeds of being “Good Neighbors.” The Clark Memo effectively removed the Roosevelt Corollary, which authorized United States’ military action in Latin America, as part of the Monroe Doctrine. The Coolidge administration denied this policy, pointing out that the Monroe Doctrine applied to America and Europe, not between the U.S. and her southern neighbors. At the same time, America retained her rights as a sovereign nation just as any other Republic should. This is why the American delegation won the argument that transpired the following day between the Pan-American representatives after President Coolidge left.

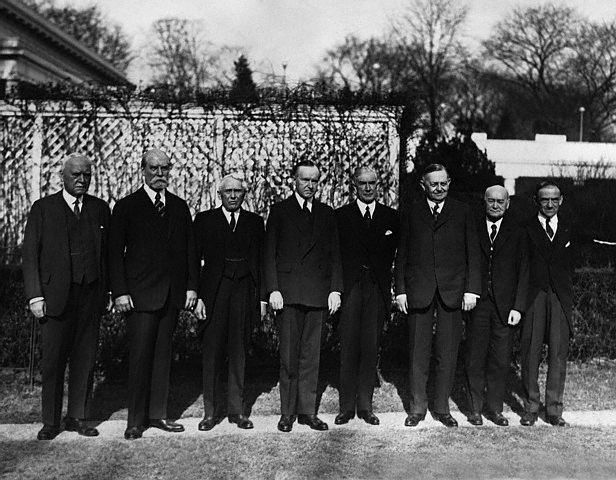

Members of the Pan American Conference to assemble in Havana, standing here on the grounds of the White House. L to R, they are: Judge Morgan J. O’Brien, New York; Charles Evans Hughes; Secretary of State Kellogg; President Coolidge; Henry P. Fletcher, American Ambassador to Italy; former Senator Oscar W. Underwood; Dr. James Scott Brown, Washington; and Dr. L. S. Rowe of the Pan American Union. Courtesy of Underwood/Corbis.

Whatever one thought of “American Imperialism,” everyone had to agree that each Republic of the New World, to have national sovereignty, must reserve the right to act militarily on behalf of its citizens and property under the law and within the limits of its constitutional forms. To lose that case would hurt the sovereignty of all the Latin American nations, down to the smallest of them. However imperfect the practice of that ideal was, it was up to each nation’s people to keep laboring toward it and not abandon one another for the jealousies, hatreds, and class warfare of the Old World.

Instead of reinterpreting history by what happens afterward, we would do well to understand the times on their own terms. In so doing, we see President Coolidge exemplified a strength of leadership and moral clarity we have not had in the United States for some time. He led by example, using the impact of the Presidential word to defend the righteousness of the rule of law and condemn the violent, lawless, and evil. His shortcomings are the frailties of human nature not the deliberate disdain for a government of laws or an ingrained hostility to the very existence of American ideals. We see Coolidge’s visit to Cuba in its proper light, as an important step of a coherent foreign policy that succeeded as any policy can ever succeed, through the moral strength of the people, in direct proportion to their commitment to liberty, opportunity, and equality under the law.

President and Mrs. Coolidge with Ambassador to Mexico, Dwight Morrow, attending the International Conference of American States, almost a year after the trip to Havana, December 1928.

Nicely done article. Where are the Calvin Coolidges of the 2016 election season?