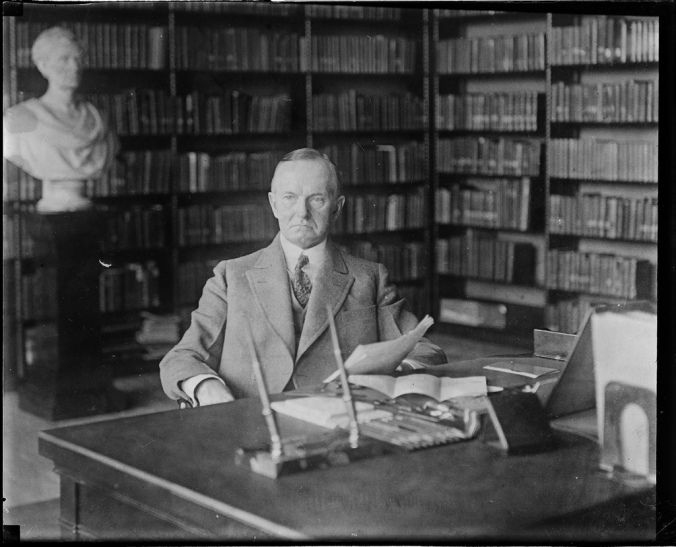

Calvin Coolidge, who passed away this week eighty-four years ago, understood the place and purpose of silence. Living at a time when the nation seemed in a hurry to go bigger and do grander, sensible of its burgeoning power, eager to demonstrate its new-found influence, and hungry to accomplish great things, Coolidge accurately grasped the mood of the culture and psyche of the country. At the same time, he was personally antithetical to many of its impatient and reckless qualities. Just when America seemed ready to speak louder, brasher, and more volubly than ever before, Cal exemplified the inner strength that silence is still necessary. There is a time to be silent even now.

Sitting on the front porch of the humble Homestead in Plymouth Notch, Vermont, Coolidge once told close friend Henry Stoddard, “I never knew so much meanness existed in the world as I listened to in Washington…nearly every man who came was seeking something–either office or legislation he desired or defeated. Few came to urge measures or men for the public good – though nearly all professed it. I had had some experiences of that kind, of course, in other executive positions, but I was not prepared for so much of it and with so much persistent under-cover pressure. It seemed strange to me that a President, if he is to avoid mistakes, has to suspect and resist almost every suggestion from callers until he can look into it most searchingly–and then usually ignore it.” Washington has not changed these last ninety years.

Henry L. Stoddard, editor of the New York Evening Mail and author of two books featuring remembrances of the former President, Mr. Coolidge.

Then, Cal came to the point. Behind all that silence there was no cold, vapid body of a do-nothing, empty-headed vestige of an obsolete era but a quick, active mind and a sensitive conscience about duty, oath, and service to all Americans, not merely the petitioners who crowded his office each day. The wise former President disclosed, “Some of my visitors, after leaving the White House, criticized me to others for my silence. If they had known my thoughts while I listened to them they would have praised me for not speaking.” While we may be curious at what Mr. Coolidge must have thought in each situation, and be confident that whatever he would have said was well-crafted, probably witty, and on occasion, unnecessarily harmful.

It was not that Cal said nothing at times because he had nothing to say but rather he manifested the discipline to place more importance on listening than rushing to the nearest microphone. He led with no less focus and intensity than any modern President yet shrouded his command of the details and responsibilities through quiet competence, careful delegation, and the wherewithal not to lose himself to the pressures of DC. He had the perspective to see through the bluff and bluster, the courage to explain the reasons (at times difficult and unpopular) for his decisions, and the restraint to guarantee nothing about the future. He refused to raise expectations on even the smallest, most attainable goals because he had seen enough of life and public office to know what obstacles can suddenly derail the most idealistic and worthy campaigns. He saw success not in what Washington could do (even if empowered for “good”) but in the courage of citizen and public servant alike to roll up sleeves, attack waste in all forms, and demonstrate the determination and maturity to preserve true freedom.

He enjoyed a popularity of depth and sincerity by refusing to make pandering promises to anyone, however close the individual or interest. His undiluted fairness and sense of discretion kept him from many of the pitfalls Washington’s clique has made and seems content to keep making.

Could it be said, though, that we need a loud, boisterous leader with the swagger and confidence – if not much substance – to carry us back from the brink? In effect, do we need Coolidge any longer? He served his purpose in his generation but what could he possibly have to impart to the 21st century, especially with a businessman at the helm?

Our own ignorance of Coolidge is the problem not any supposed irrelevance on his part. Mindlessly prejudiced by the notion that business owners inherently grasp the times, political and cultural, we assume CEOs and Executive Directors make better politicians than is historically warranted. Businessmen manifest an equal (and often greater) share of ignorance about politics yet we would entrust our most important public decisions to those hardly unbiased or informed hands. At the same time, accumulated wealth is regarded with suspicion and distrust, as if all wealth is derived through nefarious means.

Coolidge never owned a business but he directed one of the most important states in the Union (especially at the turn of the twentieth century), trimming down 120 departments and agencies into twenty offices. He oversaw one of the most volatile social periods in American history, the especially violent year of 1919. He stood fast on the principle that law enforcement must not leverage public safety on collective bargaining advantages, social experiments or political affiliation, however underpaid the Boston department was. Moreover, while he could have left the selection of personnel to his successor in the Governor’s post, he tackled it himself, making decisions that above all observed a fair matching of ability without engaging in any cynical “horse-trading” of political debts and favors. His list of selections were met with deserved praise for a solid judgment of men and measures.

In the White House, he oversaw the incrementally growing budget of the Federal Government, ably supported the Executive staff as his own household (an obligation coming out of the President’s then $75,000 salary), maintained an annual $1 billion surplus for six straight years, a record not replicated by any President since. His marshaling of the Budget Bureau program year after year, under the direction of General Herbert M. Lord, enabled both the interest and principal to be paid down on the nation’s debt (a 26% reduction on the latter), with the annual surplus also going back to Americans in tax relief, the basis for the greatest economic boom America had yet seen.

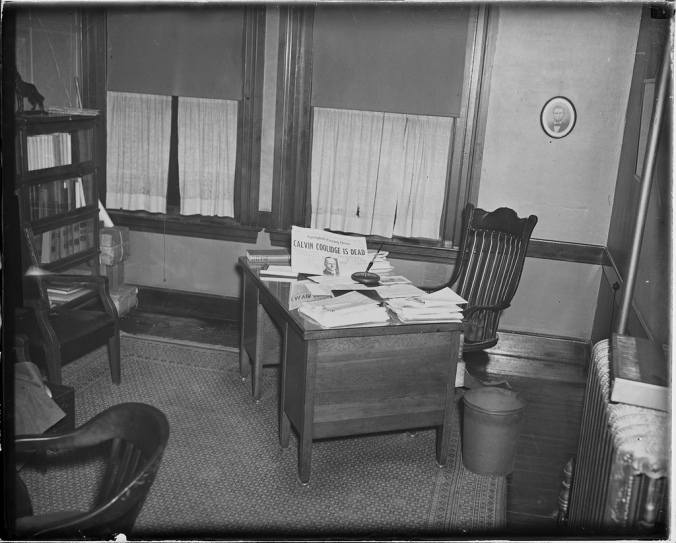

Coolidge’s old desk at his law office in Northampton, Massachusetts, shortly after his passing in January 1933. Courtesy of the Leslie Jones Collection.

However, there is perhaps no apter example of business acumen failing to translate to sound political leadership than Herbert Hoover.He was a miner by trade and an engineer by outlook, approaching every task with his meticulous, hands-on nature. He had organized the rescue of over one hundred thousand Americans caught in the chaos of closing borders at the beginning of World War I. His logistical mastery of food, supplies, and diplomatic aid spared untold lives. As Germany invaded Belgium, he took up the task of feeding, clothing, and supplying the besieged Belgians. He had lived most of his life abroad (from China to England) and made his first million as a young man. No political partisan, he was named head of the U. S. Food Administration by President Wilson. Hoover had concluded from his work in Belgium that administrative control from the top was essential to any public relief project.

Even after 12 years in Washington as a bureaucrat and Cabinet-level manager, Hoover remained unshakably convinced of that conclusion despite all the evidence to the contrary shown to him during the Coolidge years. He would apply the same business model to the office of President – failing to understand how government in America worked and how solutions are best attained by those closest to each problem. He was mystified by the expectation that Congress had any role worth recognizing at all. With disastrous results from his micromanagement style and by investing all decisions in the Office of the President, Hoover laid the foundation not only for an economic plummet, the return of deepening budget deficits, and an Executive authority overburdened by its own good intentions, but helped kill a constitutionally-guided Presidency. It failed to discredit the real culprit: the quest for business prowess as the saving ingredient of sound national leadership.

Snapshot of outgoing President Coolidge and incoming Herbert Hoover, March 4, 1929. Coolidge, having completed a remaining stack of official papers, orders and correspondence, was relieved to leave town as soon as he could. Leaving the “Wonder Boy” (as he called Hoover) to bask in the limelight, he insisted the President’s staff go attend the Hoovers rather than accompany the Coolidges to Union Station. They reluctantly complied.

On the contrary, Hoover illustrates that businessmen do not inherently make superior Presidents. “Outsiders” do not either, as Jimmy Carter underscores. But then, generals don’t exactly hold perfect title there themselves, from Zachary Taylor (who forever demolished his adopted political party as a national organization) to Franklin Pierce (who did more to hasten war than any other with his timid posture toward the Kansas-Nebraska Act). Who remembers Pierce at all these days let alone knows that he was once a Brigadier General during the Mexican War? Those commonly classified “life-long politicians” can hardly claim advantage in the comparison either, as LBJ followed by Nixon left America with the enduring costs of the “Great Society,” the psychological loss of the Vietnam War, the creation of the EPA, and the beginning of a monetary system of subjective value. One of the best leaders of recent memory began his career as a lifeguard and then an actor (Ronald Reagan).

The point is this: The belief that business leadership is both an inherent qualification and vital necessity for public office is a myth. We feel those who reside at the top of large businesses are equipped to make the “tough” decisions, “face facts” and be brutally unsparing on budgets, expenditures, and the more efficient use of resources. There simply is no one set of experiences that bring this rosy ideal pre-packaged into the White House. Businessmen no more instinctively balance money and competently direct personnel than military commanders do. Incompetence is no respecter of persons. It attends every vocation. We would do well to seek something more than “business success” in our increasingly desperate (yet cavalier) approach to selecting our leaders. We would do well to look first at character. No President, no leader of any caliber, ventures upon an office with full knowledge of what the future holds personally and professionally. It is the strength of a person’s makeup and quality that will rise to the occasion or retreat and self-destruct.

The Coolidges glad to be home at last in Northampton, March 5, 1929.

Many Americans feel a palpable relief at finally achieving a long-sought dream: A leader who has risen to the pinnacle of the business world and now is President. Of course, we know (as Dr. Burton Folsom powerfully articulates in The Myth of the Robber Barons) not all entrepreneurs are capitalists and not all businessmen are altruistic public servants. We may find that our next President is everything we hoped for and more. If so, he may become the exception that simply proves the rule about businessmen in politics. Whatever the next year brings, it will not be without some unexpected sacrifices, a summons to give something up that even the most patriotic of us will find difficult to do. As Coolidge knew, there was a proper place for silence. When he could have told any one of his thousands of visitors what he was actually thinking, he practiced the discipline of an adult, a leader who above all understood all leadership begins with mastering one’s self. Without a filter, without discretion, without a solid sense of purpose and proportion, he knew he could easily have been swept away in the torrent of Washington’s fantasy world and never accomplish a thing.

The peril America faces is not yet behind us. Some of its most trying days are ahead whether we like that or not. Whether we have the strength to face the full consequences of what we have sown as a nation remains to be seen. Our next President may regard himself too busy to appreciate the need to refrain at times but if he intends to succeed, he will have to learn one inescapable (and perhaps most difficult of all) lesson: there remains a place to listen and, having listened, a purpose for silence.

Every side comes with wish lists of goals. He cannot fulfill them all and will only accomplish a specific few. This is why downplaying every task is imperative. If the results come, they will come as a pleasant surprise that action could be taken. If results never materialize, there is usually good reason for that outcome and no violence to the Office has been done. Even his own Party and political friends will find disappointment. He should not be an instrument of a Party or obligated solely to those who voted for him. Having made so many assurances, he will be hard-pressed indeed to fulfill even a percentage of them. Perhaps he has already defeated his agenda and will have to find another one. Time will tell. From now on, he would do better to practice some Coolidge restraint.

Like Coolidge discovered, the Office reminds the occupant how small he truly is and how powerful the forces are that have shaped its burdens. It gives much and so requires much in return, the emptying of individual personality before the Office. The Presidency will ever be a thankless service but it should matter less what our next POTUS promises to do and be than the things he refrains from saying and doing. It is easy to promise and easy to advertise sweeping guarantees in advance. “He stands at the center of things where no one else can stand.” Coolidge learned how difficult it is to actually govern, to hold back when the temptation is to let go, and deal with the silent accomplishment of tasks than with glorious proclamation of deeds hoped for and dreams envisioned.

As Coolidge would note, explaining why he declined to run again in 1928, “It is a great advantage to a President, and a major source of safety to the country, for him to know that he is not a great man. When a man begins to feel that he is the only one who can lead in this republic, he is guilty of treason to the spirit of our institutions.” Presidents fail not only by obstructing input but when they pander to every petition and request, converting the appropriately limited scope of the Office into an Oz-like realm of unrealistic expectations with the desire to keep everyone happy. The President serves the entire people, not a favored minority whether that minority is Republican, Democrat or “Other.” When the Office depends on the man and operates at the behest of a select few with exclusive access to public councils, we are disloyal to what our ancestors sacrificed to leave us.

Paraphrasing Cal on another occasion, we are no more at liberty to excuse this favoritism if perpetrated by Republicans to protect Republicans than if the reverse were true. What is wrong for one is wrong for both. When the Office becomes simply the plaything of national committees, we are helping (just as Hoover unwittingly did through executive fiat) to murder our own institutions. If he takes time to listen and restrain himself, the next President will find Coolidge is not so distant or out-of-place in this 21st century after all but is, in fact, quite near with much to help heal wounds and confront our unnecessary divide.

Daniel, President Coolidge passed away on January 5, 1933 and I was born on January 5, 1953. Exactly 20 years to the day. There is something supernatural in that, or something out of the twilight zone. J.B.Gabriel

This is an excellent post. Coolidge was an incredible person and I wish he received more attention in our history classes. Thank you for continuing to share his wisdom!

Great post as usual.