While there are elements of the 1920s that baffle and even offend today’s hypersensitive climate, the fashion of that era remains as popular and alluring as ever. People across all spectra find the suits, dresses, hats, and accouterments of those Roaring Twenties (wherever they are seen) sends a vivid and powerful statement. It demonstrates the careful investment in personal improvement that drove much of that decade’s attitudes about appearance. Of course, every generation has vanity and covetousness but it was with a thought to those with whom we associate and interact that gave dressing up its place of importance in the social sphere. It exhibited a level of respect for others and the humble recognition that individual expression was not the fulfilling or all-encompassing virtue that it so often pretends to be nowadays.

It is again cool to dress up because of the clarity of place and purpose it inseparably provides. It shows you are worthy of being taking seriously enough for me to dress up, to invest quality in you not just the “gift” of my presence.

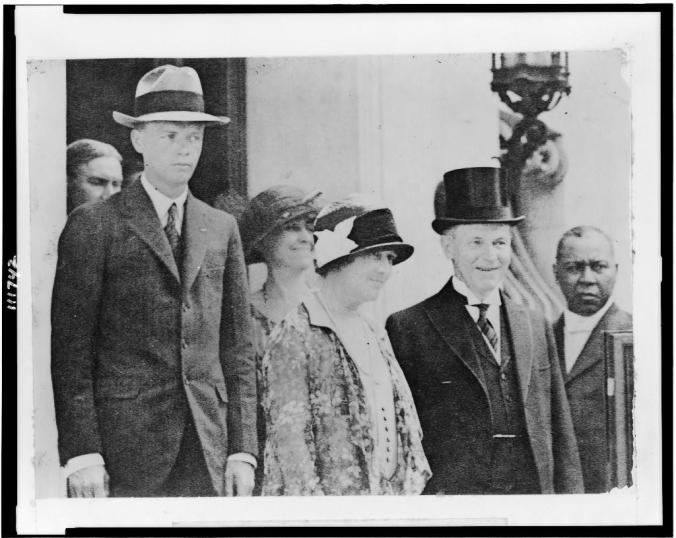

President and Mrs. Coolidge welcoming Charles Lindbergh and his mother, upon his historic return to the United States following his solo crossing of the Atlantic, June 12, 1927. Lindbergh, no fan of formal clothes, wore the suit picked out for him by the President during those public appearances.

Calvin Coolidge, born in one of the most remote corners of the country – Plymouth Notch, Vermont – understood this exceedingly well. He understood the care which one shows for one’s appearance corresponds to the care one demonstrates for other people, especially the lowest and weakest among us. In defiance of every social convention, we console ourselves in the illusion that we are freer than our ancestors only to discover that our “freedom of expression” conveys both our contempt for other “free” individuals and also our indifference to that fact.

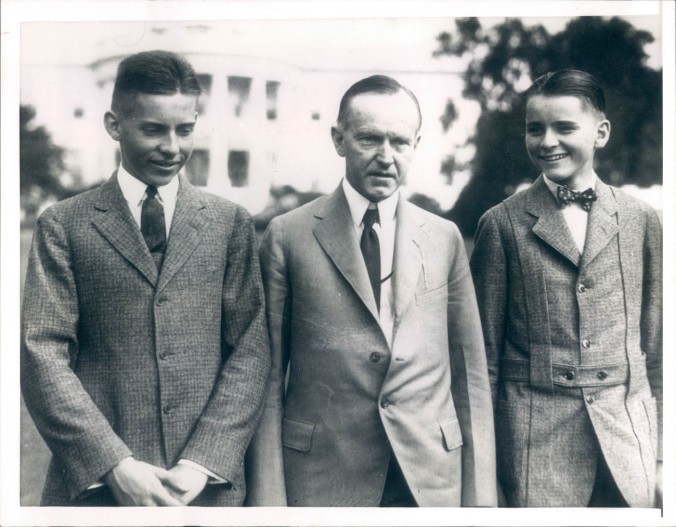

Some, when they learn that Calvin Coolidge selected what his teenage boys would wear each day, are horrified at so invasive a repression of personal freedom. While it is easy to fault this father for his severity at times, the importance he placed on one’s dress is missed in the shuffle. True, he was President of the United States, a role we still feel warrants formality, at least during “working hours.” Yet, when it came to his appearance, Coolidge made no such separation between the highest office in the land and his lifestyle. He refused to go anywhere (even as a younger man) not dressed at least one notch above the occasion. After the White House years, he even forgot his hat once and had to coordinate with his secretary to retrieve it, too embarrassed to step out of the car minus a complete outfit.

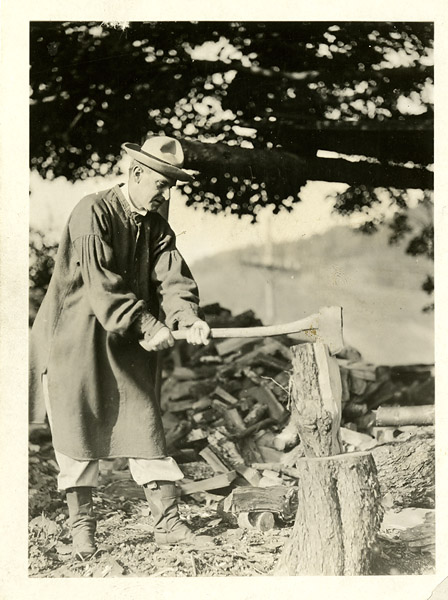

Wearing his grandfather’s frock as he worked on the family farm was as much an honor he felt due to its original owner as it was an expression that clothes declared role and purpose. It was the natural and suitable attire at work on the farm. When the press misunderstood the gesture and wrongly attributed it to a public pose, he would not wear the garment again but ever after wore what was not suited to chores but had been his chosen outfit all of his life: a daily rotation of formal dress shirts, suits, shoes, and ties. He would even appear with the gift of a headdress in South Dakota and ride in ten gallon hat on horseback without ever shedding the full suit.

We may laugh at what seems so absurd now about these instances but our cavalier disregard for public obligations and utter callousness for what is socially appropriate is no less ridiculous today.

His boys, John and Calvin Jr., would be expected to demonstrate that same courtesy and regard for others wherever they went, whatever the occasion. They were the children of the President of the United States. To the Coolidges, this had nothing to do with the specific people who occupied the office at any given time. This was not about making the boys’ parents look good. It was about the social debt the whole family owed the Office, the people of the country, and a standard of excellence in life as a whole. They were dressed up not to impress but to serve. It was for others not for themselves or some absolute right of expression that guided their care for appearance.

The Casual Revolution has certainly transformed society but as Mr. Boyer observes at First Things, with liberation does not come fulfillment. We are finding what Coolidge knew (and was obvious to most of his generation) had merit all along. Every time my family and I go in our 20s garb to introduce Coolidge, we see the electric response dressing up still means today.

Absorbed by the shattering of anything outside the ever-expanding scope of individual rights, the weakest and smallest are being crowded out at every turn. Some insecurely attack anyone who faults one’s appearance as if it were a fascistic intrusion on one’s very being. What this rock of offense exposes is the right of the strong to trample the weak without social consequence, no guilt imputed or redress due. This says, in effect: My comfort is paramount without a thought given or needed to anyone else, anywhere. A culture that has embraced complete moral egalitarianism has arrived at the brutal destination that no one is deserving of any respect or consideration. I owe nothing to anyone, we scream, so why not advertise (by my appearance) my indifference to that fact before all the world? I am more important than both you and this occasion.

When we rediscover that each of us lives not to him or herself alone, however, but has public and private responsibilities to others, we dress not to selfishly fulfill a god of absolute personal expression, who remains blindly unconcerned about the impact of our actions or the message of our appearance. Dressing up repays that honor befitting the occasion and due humanity. We dress to meet the one debt we owe more than any other: to love one another. We dress in recognition of the God who made us all in His image and calls us out of our indifference and indulgence to empty self, as Christ did, for our neighbor.