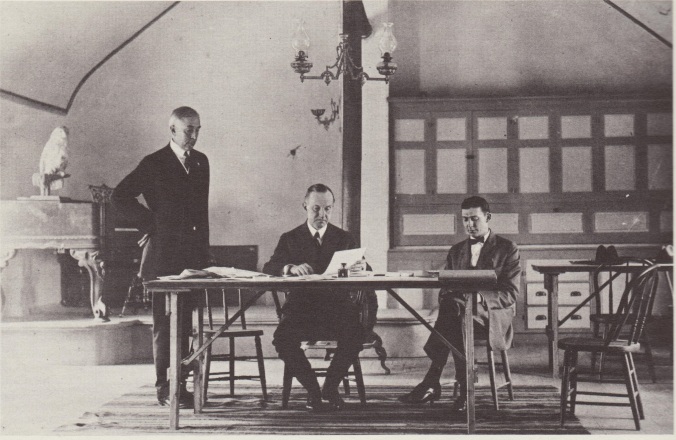

Working atop the General Store at Plymouth Notch, summer of 1924. L to R: Secretary C. Bascom Slemp, President Coolidge, and stenographer Edwin Geisser.

Calvin Coolidge was a master of administration and time management. He knew how to process the most daunting workload, leaving each day’s desk clear and ready for what tomorrow would bring. Each day brought something new. It gave practical expression to his old maxim: “Do the day’s work.” A large portion of Presidential responsibility is handling the paper that runs through the office. He stands as one of the best executive administrators the Presidency has yet to see. Moreover, he knew the “secret” of that success. He once visited the house of poet Emily Dickinson in Amherst and had the opportunity to view some of her manuscripts. As his focus turned from page to page, he calmly gave his appraisal: “She writes with her hands. I dictate.” He certainly did, relying principally upon his personal stenographer, Mr. Edwin Geisser, for the press conference transcription, voluminous correspondence, daily memos, and frequent addresses making their way from the President’s mind to millions present and future.

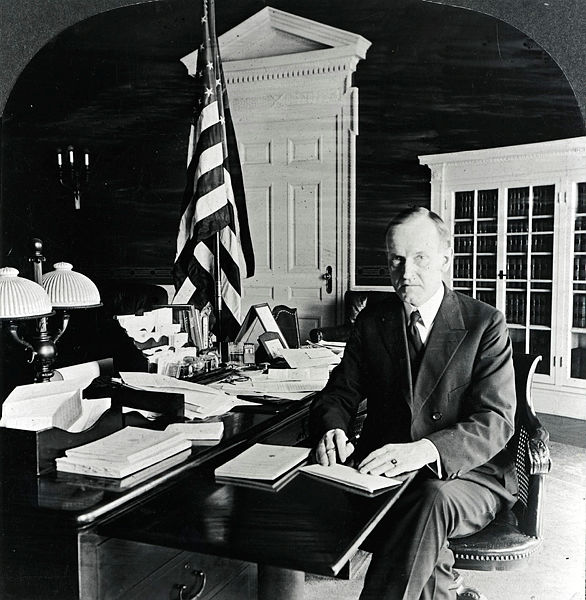

His pencil marks preside across thousands of documents but, ever efficient, they rarely appear with the content itself in his handwriting yet they are unmistakably his own. The handwritten exceptions have become some of his most famous statements (like his “I Do Not Choose to Run for President in Nineteen Twenty Eight” or his Christmas message of 1927).

When Mr. Geisser had been tasked elsewhere, the work could not wait for him, that would be inefficient. One of the President’s backup stenographers was Mrs. Bernico Ponton, who usually assisted Mr. Geisser but also helped J. Stuart Crawford, one of Coolidge’s in-house researchers. Interviewed by the Springfield Republican in 1927, Mrs. Ponton’s distinction came not only from her skills for rapid transcription but also as the only woman to whom Cal dictated letters. Interestingly, Mrs. Coolidge never dictated letters but wrote them in longhand. If typing was to be done by “Polly” Randolph or Laura Harlan, it would be the First Lady who would write the letter herself. She enjoyed typing on her own typewriter so much, even that stage of the process would often witness her tapping away the reply herself.

Calculating the various pensions of veterans appropriated by the “Bonus Bill,” taken at the Veterans’ Bureau, November 1924. Photo credit: Shorpy.

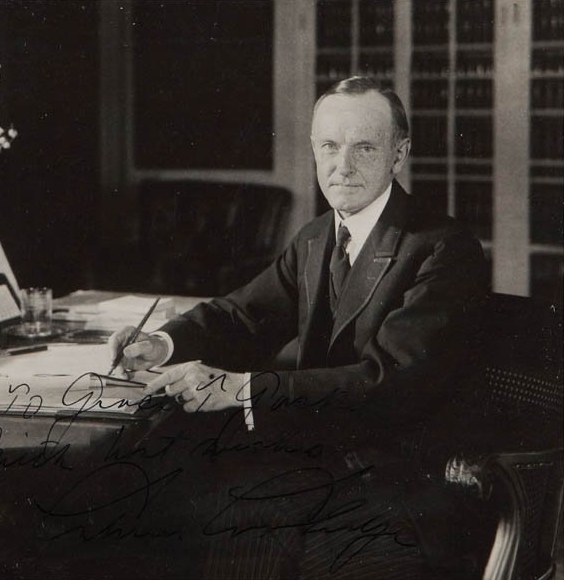

Mrs. Ponton, an experienced office manager in her own right, setting out on her career straight from high school in Maine, began working in Boston then at the Veterans’ Bureau in Washington to be shifted to the White House at the outset of the Christmas holiday in 1924. She found Mr. Coolidge to be the best dictator she had known. He never walked around, paced the floor or tore out his hair as he dictated. He never agonized over a single word. Instead, he sat beside the large mahogany desk in an armchair, working out quietly and exactly what he wanted to say. Once he began, he stated the entire sentence, rarely changing any of the wording and never struggling to find a better way to say what he had said. He had already thought it out.

If he had one fault, Mrs. Ponton said, from her professional point of view, it was this: He had such an extensive vocabulary that it would force her to search out a dictionary for the obscure and unique words that seemed to effortlessly be at the top of his brain, ready to capture the precise meaning he wanted to convey. His letters, characteristically, were usually terse and concise, a source of many a humorous anecdote in their own right. For routine mail, as White House postman Ira Smith could attest, it received only the briefest glance and a rapid-fire note in pencil at the top of the letter, issuing what instructions he wanted for its reply, to be carried out by secretaries.

Mrs. Ponton was always on time, unlocking her desk at 9 each weekday morning, and ready to work. She witnessed some of the era’s most exciting moments, including the Lindbergh visit and the chaotic aftermath of Coolidge’s refusal to run again. She and her husband enjoyed the closeness to the White House in an apartment a few blocks away and, in an office of 18 people, the Coolidges meant more to them than mere employers. They would become family.

Fascinating as always, Daniel!

Thank you, John!