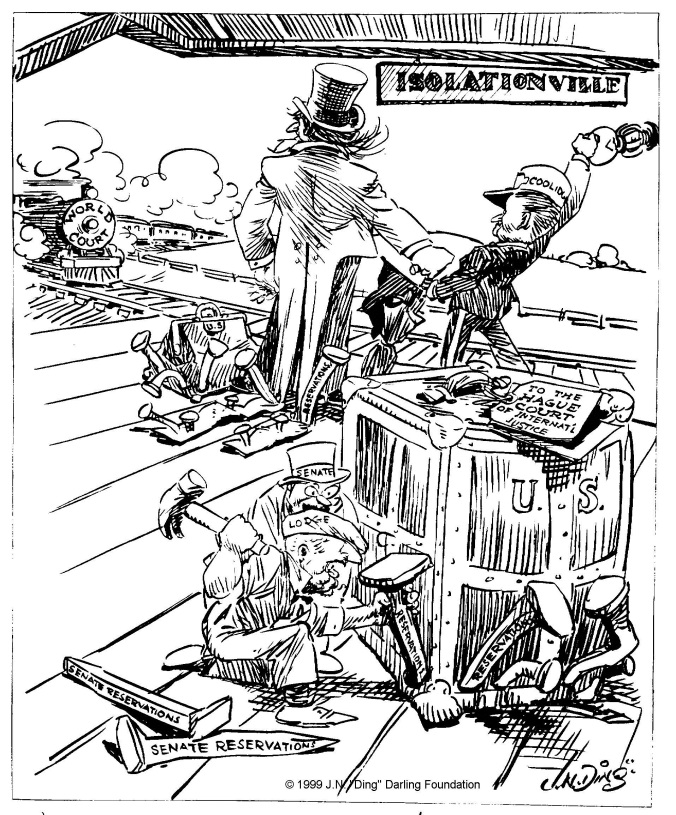

“Begins to look as if we never would get out of this jerkwater town,” by cartoonist “Ding” Darling, Des Moines Register, May 26, 1924. Here it is noteworthy to point out that Darling illustrates it is the Senate, not Coolidge, attempting to keep America in “Isolationville.”

Coolidge is still a favorite whipping post for the notion that the world erupted into global conflagration for the second time in the twentieth century in part, at least, because of his apparently isolationist foreign policies. It is claimed, these policies set up a situation where America disarmed, buried its collective head in the sand, and simply outlawed war with the naive expectation that evil would just go away. How obviously silly, these “historians” opine! How obviously short-sighted the generation of the Twenties was, they say! It makes for a convenient narrative, if only it were true.

Somehow, inexplicably, America in the Twenties is supposed to have retreated from the world because it declined to join the League of Nations at the conclusion of World War I. At the same time, participation in the World Court, the Locarno Pact, formal conclusion of hostilities between Central and Allied Powers, war debt negotiations, various arbitration conferences, and several other efforts do not seem to count as international involvement. It is as if keeping American interests independent of and unfettered by international organizations precludes the only means of valid participation. The lack of that membership, it seems to some, is tantamount to encouraging another descent into global conflict. In truth, America was no less present in world decisions and clearly becoming more involved in its return to a peacetime basis. Disarmament and outlawry were merely two manifestations of a very engaged 1920s foreign policy. Nor were these mutually exclusive to America’s portion of duty or to peace around the world.

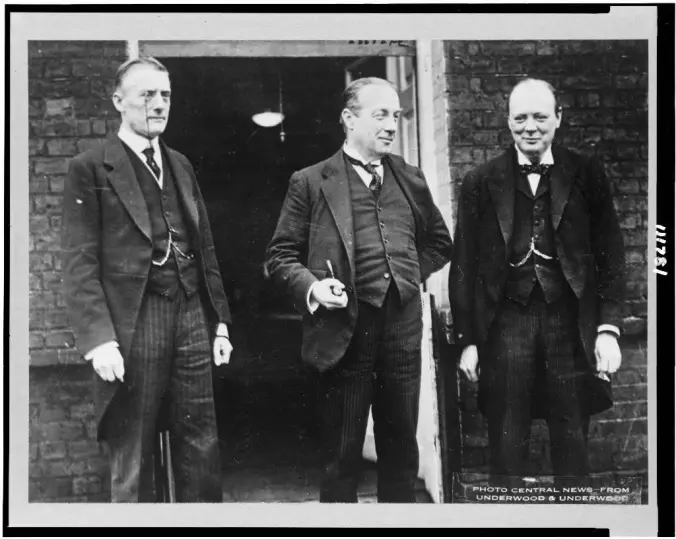

Both of Coolidge’s Secretaries of State: Kellogg, on the left; Charles Evans Hughes, on the right. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

The enabled return to “might makes right” that had spawned conflict after conflict, including the Great War, and would form the impetus for World War II, would be laid out by a different path from what Coolidge had championed. In fact, it would be a denial of the principle that each nation had its own responsibilities, deferring yet again to the concept that “someone else” would and should stand up for each nation’s own character, defends its institutions, and work out its destiny. In short, it was easier to defer making the hard decisions needed and embrace not just the rights but responsibilities of independent nationhood. As time bears out, it was America who took up that burden for many.

The first casualty of the march to war around the world was national sovereignty, whether it was Austria’s or Poland’s, Germany’s or Russia’s, France’s or Great Britain’s, Japan’s or China’s, time and again the result was to shift the burden of obligation to “someone else’s” shoulders. Dictators rose because the forces for good in their own lands failed to prevent or overcome them. It thus went to others to stop from without what should have been stopped from within. Nor is that scenario any sounder or wiser a modus operandi for the future, as time has revealed. Friendship and understanding do not require living lives for others. We bear one another burdens among the family of nations but it is equally true (and without contradiction) that each one must also bear his own load. It is still very much assumed America can and should stand in the place of making each people’s sovereign determinations in a hundred ways. It is that which has become the cornerstone of the post-war world.

For Coolidge, this was just the kind of thinking that got the world into much of the trouble it had experienced during his lifetime alone, the denial of each nation’s part or sphere of sovereignty. The expectation that America ought to carry this mantle, eagerly passed onto it by Churchill’s Great Britain, was not the linchpin of peace. Peace would not last on such terms as the downward spiral of engaging in regime-change-politics continues to bear out. It clearly took much of the pressure off Britain but in doing so pushed the United States into the same untenable position going forward. It would only work if each nation did its part. Something more than the mightiest armies and navies should stand astride the world, commanding the conduct and direction of each people. Instead, it would take a long-term process, a policy of many small steps, to reaffirm that forbearance and law — neither knee-jerk interventionism nor deployment of military force — would provide the only enduring basis for any peace worth having. Not even the well-intentioned use of American bayonets could achieve that peace. This is neither a simplistic nor naive perspective. Experience constantly vindicates it. Britain found it to be so as did Rome before it. Nothing about it is easy but it is a standard that endures when all other resources deplete and military force fails, as it eventually does.

Mr. Austen Chamberlain, Foreign Secretary (not the infamous Neville); Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin; and Winston Churchill, Chancellor of the Exchequer. Churchill in his magisterial six-volume history of the Second World War (especially in The Gathering Storm [1948]), looking back on events two decades later, places much of the blame squarely upon President Coolidge and the American administration for expecting other nations to do their part rather than, as Churchill preferred, America to do it for them.

Those who refer to the obviously “naive” Twenties sometimes cannot even distinguish them from what happened at Versailles in 1919 (which was a reboot of the Vienna Congress-approach to world affairs) and so classify them as mere extensions of Wilsonian ideals. They may not even mention Coolidge, but they clearly indict his outlook through his Secretary of State, Frank B. Kellogg, and the outlawry of war pact they accomplished with the Prime Minister of France, Aristide Briand. Oh, France is merely being France again, some wag may say. But the central contention that because there remains some injustice in the world somewhere, even such being perpetrated against American lives, it necessitates our military involvement was simply absurd, even a false dilemma altogether in Coolidge’s view. The supposedly reactionary Coolidge had a very thoughtful and persuasive alternative. It is an alternative that merits a genuine and honest reappraisal now, especially as the conflict with Iran unfolds. Consider what he said during his Memorial Day Address in 1927:

President Coolidge signs the Kellogg-Briand pact, August 1928.

“Although we are well aware that in the immediate past, and perhaps even now, there are certain localities where our citizens would be given over to pillage and murder but for the presence of our military forces, nevertheless it is the settled policy of our Government to deal with other nations not on the basis of force and compulsion, but on the basis of understanding and good will. While we wish for peace everywhere, it is our desire that it should be not a peace imposed by America, but a peace established by each nation for itself. We want our relationship with other nations based not on a meeting of bayonets, but on a meeting of minds. We want our intercourse with them to rest on justice and fair dealing and the mutual observance of all rightful obligations in accordance with international custom and law. We have sufficient reserve resources so that we need not be hasty in asserting our rights. We can afford to let our patience be commensurate with our power.

“As Americans we are always justified in glorying in our own country. While offensive boastfulness may be carried to the point of reproach, it is much less to be criticized than an attitude of apologetic inferiority. Not to know and appreciate the many excellent qualities of our own country constitutes an intellectual poverty which instead of being displayed with pride ought to be acknowledged with shame. While pride in our country ought to be the American attitude, it should not include any spirit of arrogance or contempt, toward other nations. All people have points of excellence and are justly entitled to the honorable consideration of other nations. While this land was still a wilderness there were other lands supporting a high state of civilization and enlightenment. On the foundation which they had already laid we have erected our own structure of society. Their ways may not be our ways, and their thoughts may not always be our thoughts, but in accordance with their own methods they are attempting to maintain their position in the world and discharge their obligations to humanity. We shall best fulfill our mission by extending to them all the hand of helpfulness, consideration, and friendship.

“It is because of our belief in these principles that we wish to see all the world relieved from strife and conflict and brought under the humanizing influence of a reign of law. Our conduct will be dictated, not in accordance with the will of the strongest, but in accordance with the judgments of righteousness. It is in accordance with this policy that we have sought to discontinue the old practice of competition in armaments and cast our influence on the side of reasonable limitations. We wish to discard the element of force and compulsion in international agreements and conduct and rely on reason and law. We recognize that in the present state of the world this is not a vision which will be immediately realized, yet little by little, step by step, in every practical way, we should show our determination to press on toward this mark of our high calling.”

Perhaps the most powerful nations in the world do not subsist on the continual and open-ended demonstration of that power against every challenge however trifling it be, like a body builder stopping everyone who happens to walk by in order to exhibit his prowess. Instead, power is best defined by its restraint and measure of forbearance. It is the patience we show, even when we are wronged, that actually demonstrates our strength. Our discipline befits us for the power we are entrusted.

Ambassador Morrow and the Coolidges attend the International Conference of American States, December 1928. Photo credit: Library of Congress.