The landing of a man on the moon, remembered fifty years ago today, had crucial beginnings in the 1920s. Before Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin were even born, the Twenties witnessed the combination of some of the vital components to Apollo 11’s eventual success on July 20, 1969. “Without vision the people perish,” Scripture observes but before the vision cast by Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Nixon to focus American efforts on that goal, someone had to envision the parts and the plan to achieve it.

Traveling into the higher atmosphere, not to mention space travel itself, had long captured the imagination and sparked invention. To even begin to achieve the propulsion power necessary for breaking free of earth’s protective atmosphere, the energy required had to be rethought. Russian schoolteacher Konstantin Tsiolkovsky would initiate a consideration of liquid over powder propellants in his book Rocket into Cosmic Space first published in 1903, exploring principles of rocket dynamics that would become essential guideposts through the experimentation of the 1920s. Of course, the Wright brothers would demonstrate that lifting off the earth’s surface in a heavier-than-air machine was now a reality. Likewise, just as Robert Esnault-Pelterie was presenting the concepts for potential space travel by rocket in 1913, Harold Arnold of Bell Telephones was refining the high-vacuum electronic amplifying tube that would take the ability to speak and be heard to heights which only a few years before had been deemed impossible even for Bell’s incredible telephone.

Photo credit: NASA.

Enter American college professor Robert H. Goddard, who would publish A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes, explaining his extensive findings to the world, in 1919. World War I may have significantly halted exploration into rocket power but the following decade was more than ready to make up for lost time. It was Professor Hermann Oberth’s 1923 The Rocket to the Interplanetary Spaces, a detailed articulation of the basic formulas of mathematics and physics underlying what had yet to be proven with rocketry. It was that book which came into the hands of thirteen-year old Wernher von Braun, whose enthusiasm for rockets had already screamed its arrival into fruit stands, bakeries and just about everywhere he went. It was Professor Oberth’s book that transformed von Braun from a failing math student into an instructor and before long one of Oberth’s exceptional assistants. It was the passion behind the tedium, the purpose not just the form that entranced young Wernher. Popular fascination exploded into the 1920s as Professor Goddard would not only conduct the first successful launch of a liquid-fueled rocket on March 16, 1926, but would go on to inspire still greater feats of engineering in the years to come. His inspiration upon Wernher alone was incalculable. While liquid fuel continued to spark the work of Goddard and others, German Max Valier would publish Thrusting into Space in 1928, popularizing further the potential of rocket propulsion. It seemed all the more exciting as Valier harnessed rockets to sleds and automobiles achieving previously unimaginable speeds. Fritz von Opel, John P. Stapp and Johannes Winkler would build on that delight in rocket-boosted technology. It was Fritz Stamer piloting Alexander Lippisch’s Ente (German: “Duck”) in 1928, a rocket-driven glider, that brought aviation together with where the rocket could go. It was at this same juncture that aviation was on the cusp of introducing metal-plating to aircraft beginning the transition away from canvas and cloth. It seemed the developments of the 1920s in aviation and rocketry had not only opened a universe of opportunities but had brought the prospect closer than ever before that humankind would some day step on the moon and even the planets beyond. Aviation with all its youthful energy was venturing into the transport of passengers and the transport of products, throwing wide the door to something far more than a novelty. United with rockets, where could that technology not venture for the better?

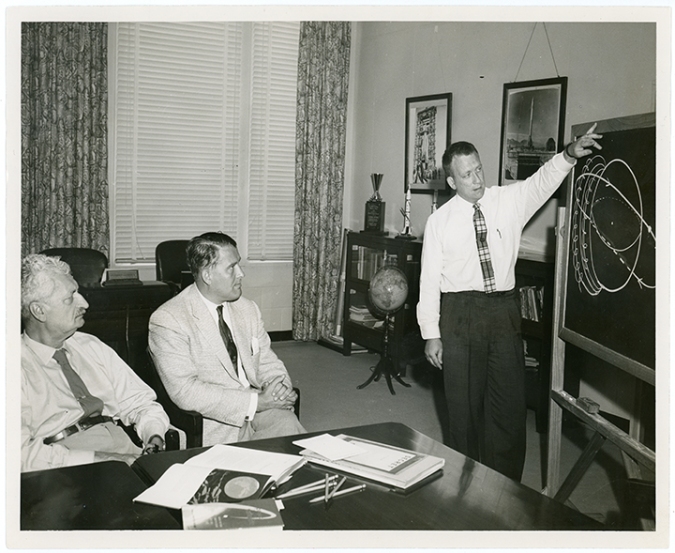

Professor Hermann Oberth sitting with Wernher von Braun as Dr. Charles Lundquist explains orbital trajectories. Photo credit: NASA, Alabama Bicentennial Commission.

Wernher von Braun

President Kennedy conferring with Wernher von Braun, May 19, 1963.

It was President Coolidge, by championing the accessibility of aviation’s continued development and innovation, even as the drums were beating to regulate the new industry beyond recognition or even consign it to military command and control, who helped in no insignificant way to protect the environment of creativity and experimentation. This was indispensable to the foundation on which later work would be based. Had Coolidge not helped keep the vision of Goddard, Oberth, and von Braun significantly freed to develop on its own without significant regulatory shackles in the Air Commerce Act of 1926, it is difficult to see how ignorant policymakers and ill-equipped bureaucrats (left to their own initiative or penchant for micromanagement) could have come up with comparable, let alone, superior results in aviation, rocket technology, or space travel in the decades that followed. Government obviously had a role from the outset, a clear partnership between the Commerce Department, the military, and the host of civilian thinkers and doers who helped lay the groundwork on which the Apollo landing and subsequent missions succeeded. It was no foregone conclusion that this was how it would start. It could have begun as the exclusive domain of military personnel or federal authorities shutting out private participants entirely. Coolidge understood it would not and could not succeed if so constituted, depriving it of the host of insights constantly unfolding in the work of engineers, scientists, and civilian technicians, any one of whom knew far more about the matter than he (or any otherwise competent public official) ever could under the best of circumstances. Great tasks benefit no less from the humble deference to informed judgment by others as a critical cornerstone for sound policy than they do from sound math and physics. Any great project always needs the freedom to adapt and adjust to make dreams reality and soar above the clouds. Coolidge knew that egos can kill the loftiest achievements. He innately understood also that government commissions and agencies are historically better at crushing the worthiest endeavors than of fostering a climate friendly to flexible problem-solving. By holding back the forces that could have thwarted these young technologies in their infancy, Coolidge helped ensure they remained capable of reaching higher heights than the eye could see at the time.

President Coolidge, opening the International Civil Aeronautics Conference, December 12, 1928. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

“Members of the Conference: This year will mark the first quarter century of the history of human flight. It has been a period of such great importance in scientific development that it seems fitting to celebrate it with appropriate form and ceremony. For that purpose this conference has been called, and to the consideration of the past record and future progress of the science of aeronautics, in behalf of the Government and people of the United States, I bid you welcome…How more appropriately could we celebrate this important anniversary than by gathering together to consider the strides made throughout the world in the science and practice of civil aeronautics since that day and to discuss ways and means of further developing it for the benefit of mankind?

“…What the future holds out even the imagination may be inadequate to grasp. We may be sure, however, that the perfection and extension of air transport throughout the world will be of the utmost significance to civilization.” — Calvin Coolidge, opening the International Civil Aeronautics Conference, December 12, 1928

Great deeds are always preceded by great ideas. Before great pilots like Armstrong, Collins, and Aldrin, there had to be visionaries like von Braun, Oberth, and Goddard. But there also had to be national leaders who helped cast the vision, focus effort, and encourage innovation among those closest to the problems and challenges of the quest. Just as Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Nixon encouraged the conditions for the magnificent goal of reaching the moon, so Coolidge, forty years before them, stood firm at a time when it was most needed as an advocate for the technological ingenuity of the 1920s. It was that stand, done in his inimitably quiet and calm way, that helped the technical and engineering seeds take root in good soil and reach for the skies. Brought together by many brilliant minds and steady heads, the contributions of the 1920s were priceless to the journey that culminated atop the moon on this day fifty years ago.

Apollo 11 launching, July 16, 1969 at 9:32am.