Mr. Cohen’s credentials had every promise of an excellent, even breakthrough, work. Educated at Stanford, then Oxford and through the Rhodes Scholarship on international relations, interned as part of the young Policy Planning team of the State Department, first under Secretary Condoleeza Rice and then Hillary Clinton, shifting to the Council of Foreign Relations in 2010 and finally onto Google Ideas and the creation of Jigsaw at Alphabet, Inc., Cohen now focuses on battling political extremism and radicalization. Cohen’s book sets out to tell the stories of the eight “Accidental Presidents,” the men who have succeeded upon the death of a sitting Chief Executive: John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, Chester Arthur, Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Harry Truman, and Lyndon Johnson. He opens the possibility that history was anything but inevitable and then proceeds to slam the door on that prospect repeatedly with most of his subjects. His book remains a clear nod to A. J. Baime’s 2017 The Accidental President: Harry S. Truman and the Four Months That Changed the World. Mr. Cohen would have done better to follow Mr. Baime’s more tightly-crafted and better focused work. At least Mr. Cohen tried, spending two chapters on Truman, dabbling in criticism over Presidential succession, noting a variety of threats and dangers to Presidential life through the years, and even recommending constitutional (or at least statutory) changes to obtain better Vice Presidents in the future. He places a high faith in political parties with a thinly veiled contempt for the electorate, however.

Mr. Cohen’s campaign activism gallops across the book, often regurgitating the partisan rhetoric of the enemies of his subjects, as if the 1848 election still leaves poor Mr. Cohen up at nights. He seems to have an especially bitter resentment toward Millard Fillmore and Calvin Coolidge. Not sure what ancestral vendetta he may have against them but not even Mr. Truman would grind his ax on adversaries as condescendingly and with half the snark Mr. Cohen deploys. As the book moves into the twentieth century, Mr. Cohen often relies on New Deal apologists like David Kennedy, himself incorrectly interpreting Truman’s position on FDR’s 1937 Court-packing Plan, which Kennedy misreads in his Freedom From Fear, wrongly citing scholar David McCullough’s seminal work which does not say Truman privately opposed the Plan, he merely sat out of the legislative debate. Then again, “If the blind lead the blind, both will fall into a pit.” The reader, however, need not follow Kennedy and Cohen there.

Mr. Cohen selects which Robert Remini studies fit the conclusion that John Tyler was doomed from the start (p.12). He does not seem to consult Remini’s Daniel Webster: The Man and His Time with any depth at all, as doing so would have provided a much fuller picture, without Cohen’s speculation, of how Webster and Tyler thought and worked. Mr. Cohen, sharing a personal affinity for Zachary Taylor (they share birthdays), seems to completely blind the author to a fair consideration of Millard Fillmore. It is most apparent when Fillmore is actually quoted, statements that resoundingly demonstrate his strength of character and sense of purpose but which occur in the midst of personal attacks upon his supposed weakness or inaction. It is almost as if separate hands collected the quotes and were allowed to paste them in wherever the fancy struck. Mr. Cohen draws deeply from his curious vitriol for Fillmore and discounts any of the substantive studies of the man, be it the work of Robert J. Rayback (Millard Fillmore: Biography of a President), or Chris DeRose (The Presidents’ War: Six American Presidents and the Civil War That Divided Them), who makes the argument that Fillmore was the most Jacksonian President of the era (DeRose, 56). Mr. Cohen simply refuses to acknowledge counter-arguments exist to the simplistic characterization of unfortunate President #13. It will not be the last time his subjects are so treated.

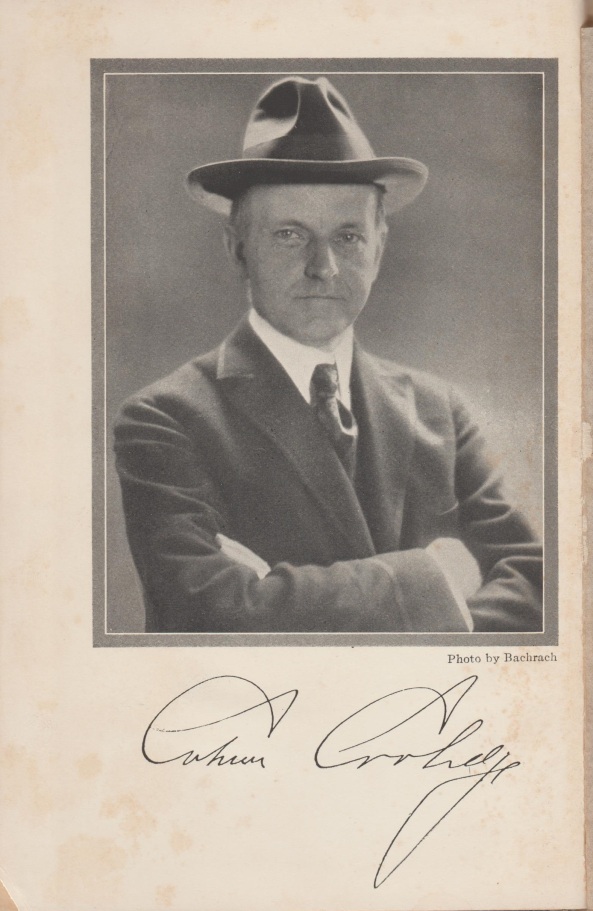

This broad generalization and selective critique only ramp up from here. It is simply unfashionable to conclude Andrew Johnson was anything but terrible and yet Mr. Cohen fails to help the reader comprehend that the historical context is needed here. Oddly, he faults Fillmore for a passivity he did not possess while denying Andrew Johnson any credit for his stalwart fight for Executive independence, a point infinitely better explored in Steven G. Calabresi and Christopher S. Yoo’s The Unitary Executive. Mr. Cohen’s wish that state election laws could have been federalized was simply not possible in the 1860s. For better or worse, subsequent campaign reforms that assumed the greater control Mr. Cohen seems to support were not on anyone’s agenda and no proposal to do so would have been taken seriously. It was, for all the imperfections, still a safeguard that elections remained with the states, a superior alternative to federal office holders in charge of the very process of their selection and disqualification. Scott S. Greenberger’s The Unexpected President: The Life and Times of Chester A. Arthur gets a courteous mention in the Endnotes but otherwise Greenberger’s thesis is discounted and marginalized out of hand. More than that, Mr. Cohen repeats the old mantra of the Grant administration’s supposed corruption, a precursor to, you guessed it, the Harding scandals. Few of us have the time to be versed in a full study of everything and so most of us rely, many times inescapably, upon the work of others. Even the work we study relies on this continuous and ongoing debate over Presidential legacies. That said, if your purpose is to tell the stories of these men, be diligent enough to tell the whole story and not broad-brush lampoons or mis-characterizations painted by one side about the other. Mr. Cohen simply accepts the wisdom handed down from on high when it comes to Grant, Harding and Coolidge. Mr. Cohen seems to have no knowledge of the substantial accomplishments of the Grant administration, not only in Hamilton Fish’s State Department but also under the leadership of Boutwell and Bristow at Treasury, who reclaimed sound budgeting, cleaned house across the departments and exposed the Whiskey Ring along with numerous other schemes when, if the whole barrel had been corrupt, no investigations would have occurred at all. As Hamilton Fish would later put it, “I do not think it would have been possible for Grant to have told a lie, even if he had composed it and written it down” (emphasis added, see in Jean Edward Smith’s intricate study Grant, 592). Mr. Cohen regards Theodore Roosevelt and Harry Truman as the two lone success stories among the “Accidental Presidents,” and yet leaves off any of the inconvenient details which might counter that conclusion with a more generous appraisal of the other six. He ventures into none of the festering conflict of the Brownsville Affair, even indicating that TR and Booker T. Washington did not meet enough to address issues (p.216). Readers would be advised to return to the more incisive treatments of TR by Henry F. Pringle and William Henry Harbaugh. Truman is praised rightly for his independence of judgment but Mr. Cohen remains oblivious to the same quality often observed by friends and foes alike about ol’ Cal. A grudging mention is made that Coolidge becomes only the second man, following TR and preceding Truman, to win election against incredible odds in his own right. The significance of this fact, including what it says about both the candidate and the people of the country, seems lost on Cohen. It seems he just cannot wrap head around it and so defaults to sarcasm and cheap shots (such as with Coolidge’s nomination by a “single fan,” Judge Wallace McCamant — not “McClamant,” p.232). Readers would be far better informed to pick up David Pietrusza’s 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents. The arbitrary and oft sliding scale with which Mr. Cohen condemns in one subject what he praises in another is not surprising but it is unfortunate. As Obi-wan Kenobi once asked, “Who’s the more foolish: the fool or the fool who follows him?” Readers need not follow his mistakes.

Mr. Cohen, for all his enthusiasm to dig into the scandals and headliners of the Twenties, settles for the tabloid sources in too many cases, leaning heavily upon Charles L. Mee’s The Ohio Gang and John Dean’s Warren G. Harding over the far superior analysis of M. R. Werner and John Starr’s Teapot Dome and Robert K. Murray’s The Harding Era. Even the Joel T. Boone Papers, Phillip G. Payne’s Dead Last: The Public Memory of Warren G. Harding’s Scandalous Legacy and chapter 2 of Paul Johnson’s Modern Times give a much more complete and honest accounting of Harding and Coolidge than we ever find in Accidental Presidents. Mr. Cohen seems confused as to which street the supposed house of scandal was, misidentifying the K Street home as on H Street (225, 226). An honest mistake, perhaps, but one that Cohen might as well use as equally hard evidence of Harding‘s guilt. It is just as well, I suppose, that Mr. Cohen works so closely with Google’s Alphabet, Inc. At least Cohen would never have to worry he might stumble upon the place looking on H Street. Mr. Cohen is so sure of what happened where and so completely convinced that the entire Cabinet discussed the shady deals of the Interior Department that he actually implicates Coolidge, Hughes, and Hoover of complicity, if not deliberate obstruction. Mr. Cohen seems ready to list the entire administration must only consist of the Justice Department, Veterans’ Bureau, Interior Department, and, maybe, Commerce and War. To him, none of the incredible achievements of Hughes’ State Department, Mellon’s Treasury, or Hoover’s Commerce exist, not to mention the rest of the Coolidge Cabinet, whatever those departments were. It appears to Cohen, the whole barrel is bad and everyone is guilty. These pathetically sweeping indictments of secret guilt may fit nicely in a 1932 campaign pamphlet but they are horrendously bad history in what is supposed to be recounting the stories of the eight “Accidentals.” Honest history requires a grasp of the historical context, starting with a modicum of respect for contemporary perspective that attempts to help the reader see things through the eyes of the times, not impose views upon them. Cohen’s handling of the Homestead inauguration is another case in point. He explains none of the differences that continue to exist between accounts of that historic night, for the benefit of the reader. He merely repeats much of Porter Dale’s side, leaving the erroneous impression that Dale virtually led a lost Calvin Coolidge by the hand, who otherwise knew not what to do. Cohen further dramatizes the account with the old Colonel bursting into his son’s room upstairs, a colorful yet dubious flourish not corroborated by those present. If Cohen cannot handle the little things, how does he retain credibility on the bigger things?

Coolidge’s legacy, in Mr. Cohen’s view, seems somewhere between a record of negligence and one of blatant dereliction. Cohen attributes blame (alongside Harding and Hoover, of course) for nearly everything that went bad in the 1930s and 1940s (which the great ‘liberal’ reformers of the FDR and Truman administrations resolved, of course). Coolidge’s role in these years, when he wasn’t sleeping, obviously, approaches something resembling the behavior of a proto-Nixon, in Cohen’s view. Coolidge’s shrewd calculation, interestingly, appears more than once in chapter six. Coolidge was certainly not the worst in Cohen’s estimation, an infamy reserved for Andrew Johnson, but he was something too difficult to comprehend in anything other than the conventional caricatures of Cal. It becomes far easier to relegate him to the old, tired cliches of those nameless failures of Republican yesteryear, those who fell asleep at the controls while the rich got richer and the country’s future got mortgaged for it all. It addresses none of the incredible popularity Coolidge kept, the genuine accomplishments on a range of problems, and certainly not a whisper of the strong constitutional record Coolidge left, superbly tackled by Michael J. Gerhardt in The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy. Gerhardt even has nice things to say about Fillmore. Maybe that is why Cohen never countenances Gerhardt’s The Forgotten Presidents. Still, there are a few interesting deviations in the narrative: Accusing Coolidge of actual guilt in the Teapot Dome scandals might be a first, at least in a long time. Coolidge’s focus on winning the election, Cohen indicates, enabled the scandals to be hushed, crafted the narrative of prosperity to cover all sins, and helped establish that arch-nemesis of civil liberties: J. Edgar Hoover, to be ensconced at the Bureau of Investigation, the precursor of – gasp – the FBI. Never mind that it was Coolidge’s open handling of the whole scandal that enabled its successful prosecution, sending a Cabinet officer to prison for the first time in history. Like Grant, Coolidge gets no points from Cohen on any of that.

Once more, the campaign operative penchant in Mr. Cohen rears its head, similarly conflating and retroactively personifying J. Edgar Hoover as the fully-formed monster his enemies would years later describe when they spoke of him. It escapes notice that the lurid personal profiles Hoover would later provide to the White House began with FDR, who took special interest in gathering the little secrets of contemporaries for possible use in political wrangling. That said, it also escapes notice that Senator McCarthy took up an investigation begun by a Republican colleague (Senator Homer S. Ferguson), referred the findings to a Democratic colleagues (Senator Millard Tydings and Judiciary Committee chair Pat McCarran), all of which remained different investigations from the one continuing simultaneously under the jurisdiction of the House Un-American Activities Committee, the latter created way back in 1938 by Democratic Congressman Martin Dies, Jr. All this begins to deviate from the point but then again it illustrates how out of his element Mr. Cohen ventures at times. He would have been better served focusing on the controversial Mr. Truman, but even then, he might have discovered many admirable similarities to Truman’s predecessor, another Man of Main Street America, Calvin Coolidge.

Excellent review!

Sadly, such histories as that of Jared Cohen do more harm than good. There is certainly little new and enlightening in them. Clio would not allow them on her altar.